An Exploration of Interurbans, Expressways, and Light Rail

So a few weeks back, I planned a series of walks hoping to highlight some specific routes to highlight the history of (ground based) travel between Portland, Milwaukie and Oregon City. The corridor is of special interest for two-ish reasons – for one, I just moved in with Olivia to a cute apartment in the Brooklyn Neighborhood about a stones throw (in a sling at least – 172 meters) from the Orange Line MAX. And also, Mark made the commute down to Oregon City for his “job” (the quotes are there since he didn’t actually get paid any money for it), sometimes borrowing my car for it. Beyond that, I have a loop I like to bike on which features the “Trolley Trail” through northern Clackamas County – so I’ve been at least mildly interested in the corridor for a while, and I think it makes an interesting case study.

To do my little case study, I decided on three walks – each highlighting a different era and thought process about how people should travel. The first walk was an approximate retracing of the old interurban route, with a few adjustments where fences or other obstacles impeded me. The second walk followed the route of the MAX Orange Line south from Portland State into Milwaukie and then to a park and ride just south into unincorporated Clackamas county. And the final walk was down McLoughlin (OR 99E) from the Ross Island Bridge to Oregon City.

Quick aside – I chose to start with the interurban rail rather than the Oregon Central/Southern Pacific/Union Pacific mainline because I felt that an entire history of railroading in Oregon was outside the scope of what I wanted to explore. Similarly, river travel (for native people and white settlers alike) was king until the 1870s at least – but given I haven’t bought the canoe I’ve been dreaming of I decided to hold off on that (very interesting) topic for now.

My primary focus on all of these walks was really to try and get a feel for the landscape and land use in the areas around. Along the old interurban route, there are countless shops, neighborhood cafés, restaurants and more. Particularly in Sellwood, Milwaukie -> Bybee -> 13th is just about the densest concentration of cute shops and mixed used development in the city. But this extended into Clackamas county as well – both Oak Grove and Gladstone have quiet little main streets where the Trolley formerly ran and I found myself wanting to stay and linger there longer than I expected.

These streetcar suburbs/interurban stop areas offer some of the best in mixed-use development, where commercial and residential uses mingle. Despite the obvious advantages of having a café or convenience store within a short walk, most modern developments are exclusively zoned for residential use – further cementing car dependence (although Portland is considered to be pretty good on this front – we still relegate most higher density and commercial areas to the busier streets which I’ll talk about in a future post). American zoning practices deserve much more space than I will give them here, but the full segregation of uses – typically called Euclidean Zoning – has it’s roots in the typical American past time of excluding poor minority groups from certain neighborhoods (Euclidean gets its namesake from Euclid, Ohio rather than the Ancient Greek philosopher/mathematician). But beyond the questionable history of the practice, it’s worth doing away with solely because it makes places less vibrant and livable. Society should be human-scaled, and designing areas for people to walk more is the best way to allow for that – which vestigial streetcar corridors are perfect for.

On the next walk, while following the MAX line I noticed a conspicuous lack of interesting places to take pictures. I mean the Tilikum Crossing is nice and all, but it is genuinely is surprising how boring most of it was. I know Portland (and by extension TriMet) have a reputation for “good transit” and “transit oriented development” but you would not get that impression from a brief overview of the Orange line. The insistence on speed puts the route along expressways and rail right of ways – not exactly the kind of place people really enjoy living or hanging out. With the notable exception of Milwaukie, I didn’t really find many places worth relaxing and hanging out in. Which I dunno, probably contributes to the lower overall ridership of the line – but I guess I’m not an urban player type (yet!).

It really does annoy me how little the regional government here seems to care about having transit projects serve actual amenities people want to go to. Only two of the stations east of the river have any sort of commercial activity within a short walk – SE Clinton/12th is close to the end of Division area and Milwaukie downtown is obviously close to all of downtown Milwaukie. But considering that East Portland is basically a bunch of neighborhoods filled with cute shops, it’s absurd that a “rapid” transit line going through doesn’t really serve any of them at all. But in conduct typical to Metro and TriMet, the alignment of the Tilikum Crossing was adjusted in the 2008 Locally Preferred Alternative Report to directly connect the South Waterfront to OMSI. Rather than serve existing centers of commercial activity (like Sellwood, or the Central Eastside), the preference is catering to vapid projections of growth in an Urban Renewal District. More on TriMet later I’m afraid – as the history of the Orange line is rich with decisions I would only describe as infuriatingly boring.

Despite my issues with the MAX routing, it’s nothing compared to the horrors of McLoughlin. Strip malls, dilapidated sidewalks and the roar of traffic were all I had to keep me company there. Charles Marohn of Strong Towns fame coined the term “stroad”, a street/road hybrid that attempts to fulfill the function of both a street (bustling corridor for commercial activity, etc.) and a road (high traffic speeds and volumes) while failing at both. McLoughlin is a perfect example of this between Milwaukie and Oregon City – but also offers a study in early (pre-interstate) urban expressway design in the section between Portland and Milwaukie. So I’ll talk about both areas separately.

From Portland to Milwaukie, I spent my time mostly just looking at cars and trucks speed by uncomfortably close to the sidewalk. It was fairly surprising to see a sidewalk at all though – since McLoughlin really does “feel” like a freeway when you drive on it from Grand/MLK viaduct to Milwaukie. But despite this freeway “feel” (entrance/exit ramps, wide lanes, etc.), the all-knowing philosopher kings at ODOT allowed some measly sidewalks to be included for pedestrian access in some areas. It may seem strange now to have sidewalks next to an expressway style road, but given that OR 99E was largely built in the pre-WWII era without an Interstate Highway System Standard to allow for full exclusion of pedestrians it makes more sense. The expressway continues through a few stoplights, at Holgate and 17th ave before turning to parallel the former Southern Pacific mainline through Sellwood – running between the tracks and Westmoreland Park. Adding greenspace to expressways has been in the vogue since the dawn of highways, giving a nice scenic view to all the motorists as they whiz back home from the suburbs. As a pedestrian, it’s nice to be able to walk with trees between myself and traffic – but I’d still prefer to be on a regular old street

The “stroad” section of McLoughlin begins just south of Milwaukie in unincorporated Clackamas county and is even less enjoyable to walk along than the expressway sections in Multnomah county. This may seems a bit strange, but at least on an expressway the stress rarely crosses your path. On a stroad, there are constant curb cuts and turn lanes for commercial access so you really have to keep your wits about you. And on top of that, the proliferation of parking means shade is a rare treat. Environments like this don’t come about by accident though – they come about based on zoning, mismanagement and surrender to the automobile. Firstly, in the unincorporated area of Clackamas county, the half mile stretch around McLoughlin is the only area zoned for commercial (or for higher-density residential – which is a whole second can of worms), so everyone who lives nearby is forced to go to the corridor for their shopping. Then, because the road itself is designed primarily for through traffic, it becomes inherently hostile to pedestrians and other non-car access. It just does not feel safe to walk down the road, and even if you do all the shops are behind a sea of parking lots – because everyone has to drive anyways. And yet, along a road like this you’ll find the only areas that the county has deemed appropriate for higher density (i.e. apartments). Speaking as someone who lived in a place like this once upon a time (Nashville, TN), I can attest to it being very hostile to existing outside a car.

Given the obvious safety issues of clustering commercial activity near high speed roads, ODOT has started to install some beg buttons and flashing lights for whoever feels brave or foolish enough to cross McLoughlin away from the relative comfort of a stop light. I find efforts like this to be too little, too late – there is nothing ODOT can do to shoehorn pedestrian safety into a corridor like this since pedestrians are the antithesis to the entire roadway design. An entire philosophical redesign seems unlikely, given the highway-centric thinking still prevalent at ODOT – so it seems we will be stuck with McLoughlin as a weird liminal space for the foreseeable future.

And so what does all of this mean? I think largely, it shows a society with shifting priorities. In the late 19th century, railroads were essentially the only way to get around other than by foot. So land use patterns and the urban (or suburban, or rural) fabric is strongly reflected in that. Places simply had to be within a short walk from places people lived, or a railway station or they would not get enough business to survive. By the middle of the 20th century, cheap automobiles lead to a huge boom in highway building and a shift in development patterns. No longer shackled to railroads with rigid schedules and stops, people were “free” to go wherever they wanted in their shiny new car. But this came with the cost of excessive amounts of land needing to be dedicated for both parking and the physical road infrastructure – which has lead to an excessive amount of suburban sprawl (on the backs of heavily subsidized highway infrastructure). Finally, in the later part of the 20th century towards the present day, state and local governments (at least in Oregon..) have tried to offer alternatives to auto-oriented development – but ultimately have failed to meaningfully shift the needle all that much.

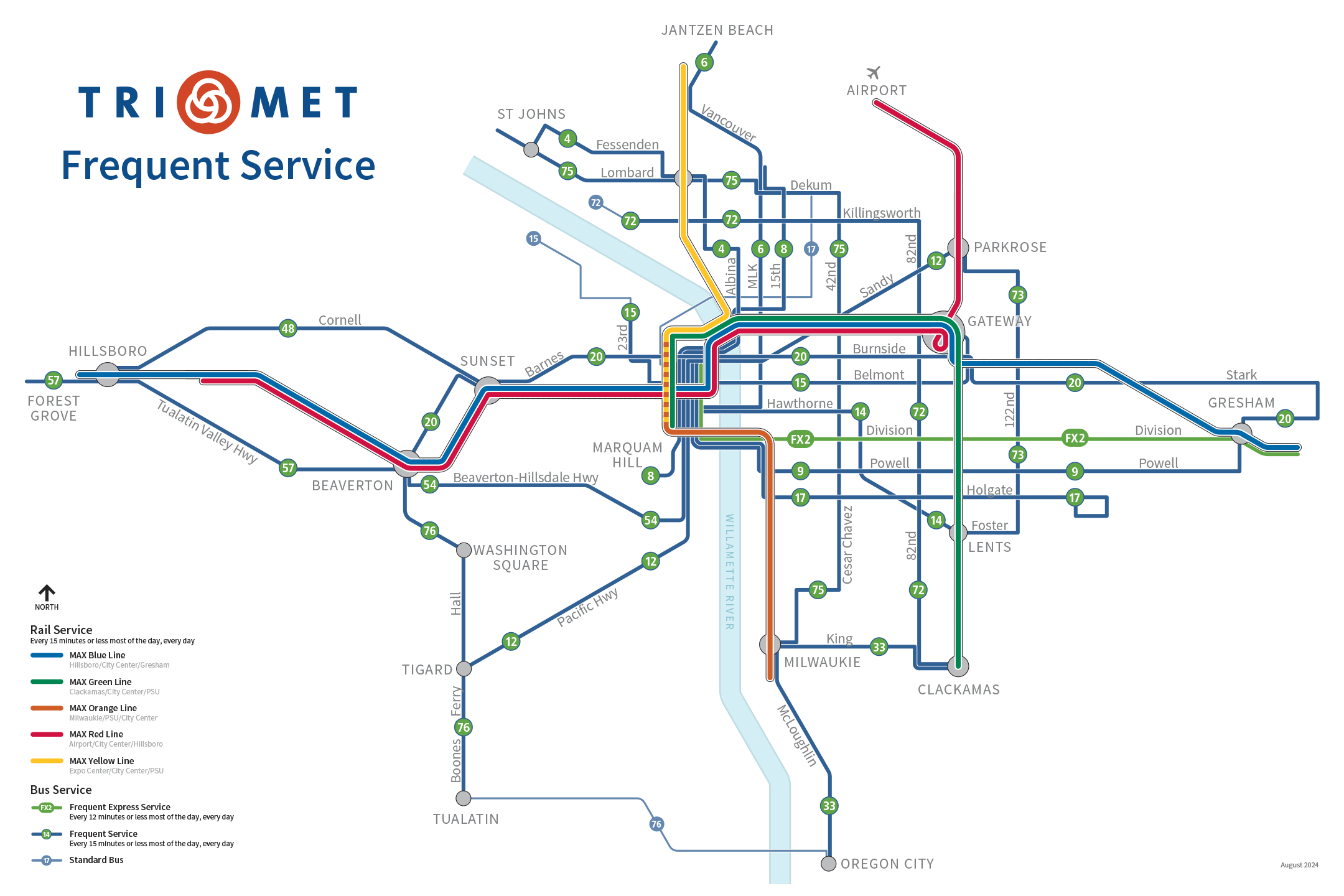

This relative failure of MAX light-rail modern transit-oriented development has failed for (in my estimation) three reasons. Firstly, the MAX operates in a similar way to a stroad in that it tries to function as a local, streetcar type service and as a fast, commuter focused service while ultimately failing at both. Secondly, the state and local governments have still spent so much more money on highway and car infrastructure, it is virtually impossible for TriMet to run properly good transit service (even if they wanted to) – in 2021, ODOT budgeted $3.2 billion for highways, and just $337 million for public transit (statewide!). And thirdly, TriMet still operates as if the only place anyone will want to go is Downtown Portland from the suburbs (especially if you consider a broader “suburb” definition – including older eastside neighborhoods which function somewhat as proto-suburbs to the West Side of Portland). Looking at a map of just frequent service lines in Portland proper, fully 16 out of 19 converge downtown (all 5 MAX lines, bus lines 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15, 20, 54, and 56) leaving just three bus routes (72, 73, 75) with any sort of circumferential coverage.

To expand on TriMet’s failure to connect non-downtown areas of the city with each other, it’s worth comparing to another much maligned regional-level transit authority in the country: SEPTA (South East Pennsylvania Transit Authority). Philadelphia and Portland don’t really have that much in common, but I think that TriMet and SEPTA operate in somewhat similar ways – most importantly being that they run transit service for a metro county (Multnomah for TriMet, Philadelphia for SEPTA) and it’s suburban fringe counties (Clackamas and Washington for TriMet; Montgomery, Bucks, Chester and Delaware for SEPTA). According to OpenStreetMap data, TriMet runs 136 different* services in the city of Portland (I believe this double counts all actual services – since a westbound and eastbound route are usually different relations in OSM). Fully 82 of these converge on Downtown (60%) – in comparison, SEPTA runs 196 different services* in the city of Philadelphia (same disclaimer), with just 34 converging into the central city district (17%). I guess downtown Portland must just be 3.5x better than downtown Philly – take that Benjamin Franklin.

But beyond the monetary shortfalls and commute focused shortcomings, there is a more pertinent philosophical problem at the heart of it all. Oregon (and Portland in particular) seem to be very keen on reducing car dependency and promoting alternatives to driving. But they are not very keen on any meaningful reduction of public space allocated to cars. There are no proposals to remove street parking and add bike lanes at any kind of useful scale, nor are there any proposals to redevelop any park-and-rides into transit style developments. The “megaprojects” that get funded are still highway expansions in the name of congestion relief (like the current “upgrades” to I-205 in Clackamas County). Meanwhile, Seville, Spain spent less than $50 million on an entire 100 km separated bike path network – largely at the expense of about 5,000 curb parking spots.

Anyways, while all this talk about bike infrastructure may seem like a tangent from a bike guy (okay it is that) – it all ties into the larger point. No local leader is willing to even consider reducing the amount of public space dedicated to cars – even in an “urbanist liberal paradise” like Portland. A while back I read a book called Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City by Peter Norton which revolves around the idea of the street as public space – and that how before 1930, cars were merely one of many users of shared street space. This seems like a strange idea now, given that almost every single street in the country is dedicated to through travel of cars – but it took clever marketing and a revolution in the way people constructed who and what a street is for to get us here. And it’s this revolution in what a street is which led (in part) to the original downfall of the American streetcar (although GM buying out transit agencies, ripping up tracks, and burning streetcars for scrap certainly didn’t help things either). But it’s also part of the trouble for the MAX system as a whole now. In order to keep costs low, much of the system runs at-grade on streets – but because of the perceived priority of largely single occupant automobiles, MAX trains run slowly in mixed traffic.

I do think that it’s great that Portland was able to build lots of rail transit for relatively cheap. But the key is “relatively” – since most of the old abandoned rail right of ways have been redeveloped, turned into roads, or sold we pay a high price for constructing a new one. This price is either paid monetarily – like with the 8 bridges needed to cross one river, two creeks and five roads for the MAX Orange Line. Or it can be paid with poor service – like how the Orange Line skirts around every point of interest between OMSI and Milwaukie, all in the name of spending less money/time in the vibrant mixed-use urban areas of Brooklyn and Sellwood-Moreland.

So all this leads to one conclusion; the car killed the Portland – Milwaukie – Oregon City corridor. Auto-oriented policy allowed McLoughlin (and later I-205) to bulldoze houses and divide neighborhoods all in the name of “fixing traffic”. Yet traffic is worse than ever – since in a bid to own the whole world, car boosters killed electric railroads (streetcar and interurban), thus forcing even more people into cars. Without reliable alternative options, traffic will continue to choke the streets and thoroughfares – but the incredibly pro-auto design of the entire corridor makes this feel like a pipe dream. When even transit projects end up catering to the car, everyone ends up losing.

Leave a comment