A skeptical examination of yet another freeway mega project.

Project Background

In 2017, the Oregon Legislature passed House Bill 2017 (what an original name) asking ODOT to fix congestion in the Rose Quarter (I am going to refer to the area as the Rose Quarter for clarity – but just know I prefer the term Lower Albina for the area). Ranked as the 28th worst trucking bottleneck in the country, and a “source” for delays for commuters, it is also the busiest stretch of highway in the state of Oregon. In the “Traffic Technical Report”, ODOT cites five northbound on/off ramps and six southbound on/off ramps with short “weave” distances (usually defined as the amount of space a vehicle has to get from the ramp into a regular lane – apologies for the jargon), which they say contributes to congestion by adding conflicts and more vehicles.

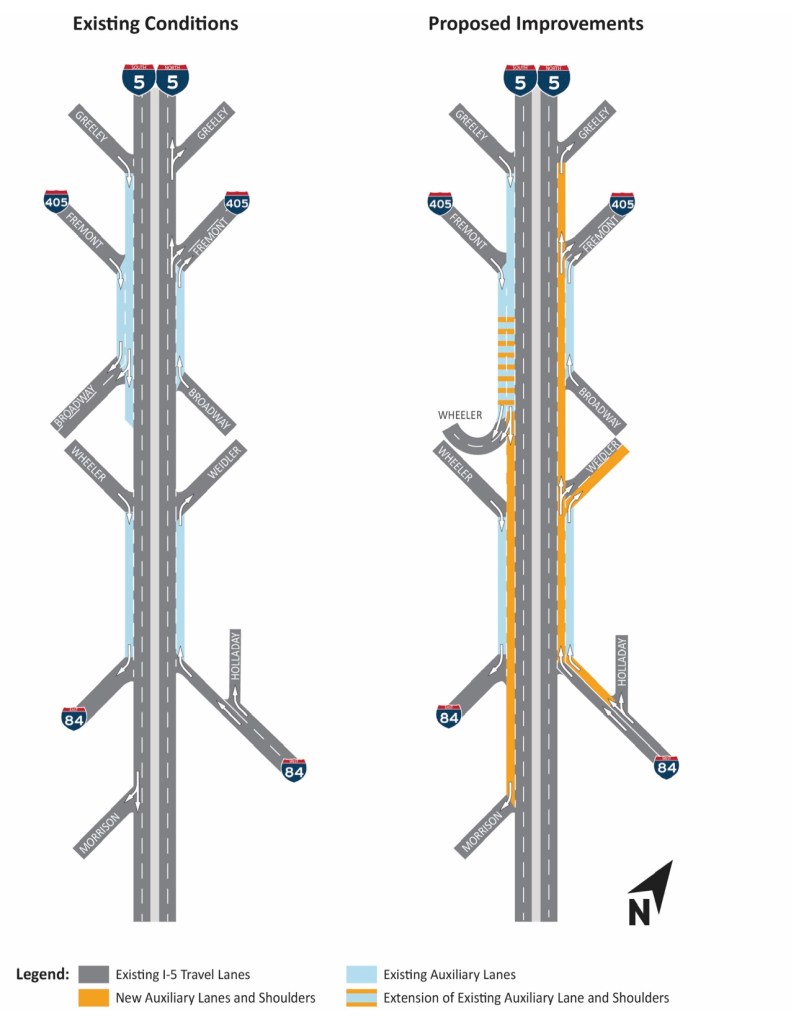

And the $1.5 billion dollar solution is to add more “auxiliary” lanes to reduce conflicts and weaving, and (after some political maneuvering) a proposal to add a freeway lid with the stated goal of stitching historic Albina together.

What the Hell is an Auxiliary Lane?

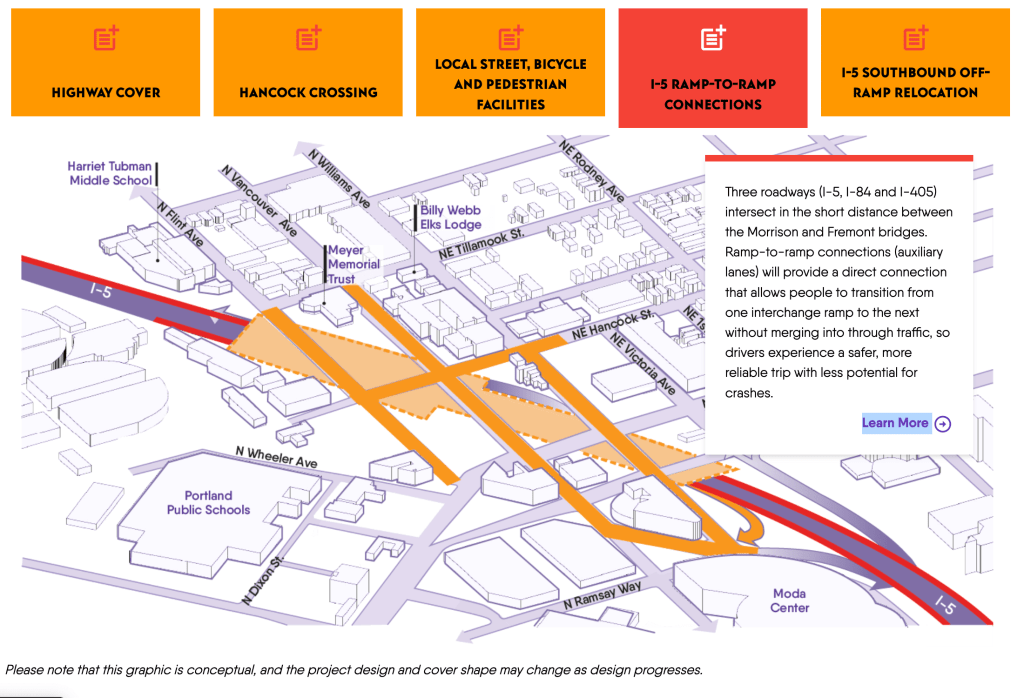

ODOT defines an auxiliary lane as a “ramp-to-ramp connection” allowing for drivers to get onto a freeway without having to merge immediately. In the Portland area, they are being used as a way to add freeway capacity between major exits – allowing vehicles to get on the freeway without having to merge onto the “mainline” of the freeway. ODOT cites “internal studies” for auxiliary lanes reducing crashes by 20-30%, and “improved traffic flow” as the primary benefits.

In my opinion, ODOT’s definition and use of “auxiliary lanes” here is rather nebulous. Saying ramp-to-ramp, but extending through three sets of on/off ramps is a bit silly to me. To me it seems that all of the benefits are really a result of increased capacity – not a special designation. Giving a driver extra room to merge is just punting the issue downstream – drivers take up as much space as they are given – and when the auxiliary lanes end, the bottleneck will just be there instead of where it is now.

Consider a trip from I84 to I405 (northbound section) now vs. with the proposed “improvements”. Currently, they merge sometime before the Weidler exit (~250 meters/820 feet), while in the future they won’t have to “merge” at all (~1300 meters/4500 feet). And on its face, this is seems like an operational improvement – but in reality, the driver will still have to navigate almost as many different conflicts and weaves as before. It does not eliminate the conflict for the I5/Weidler exit (coming from I5), nor the I5/Broadway entrance, nor the I5/I405 exit – it only succeeds in pushing those conflicts over one lane. The only conflict that is really “resolved” per se is the original I84/I5 merge – which is a good thing from a safety perspective, but just keep that in mind as a baseline.

Additionally, ODOT framing auxiliary lanes as easing congestion by giving drivers more room (or space, etc.) to merge – this is because it is additional capacity. Maybe splitting hairs here, but that “extra room” is de facto added capacity – and for a state purportedly trying to curb vehicle miles traveled for climate reasons, adding capacity is tantamount to shooting yourself in the foot.

Project Branding

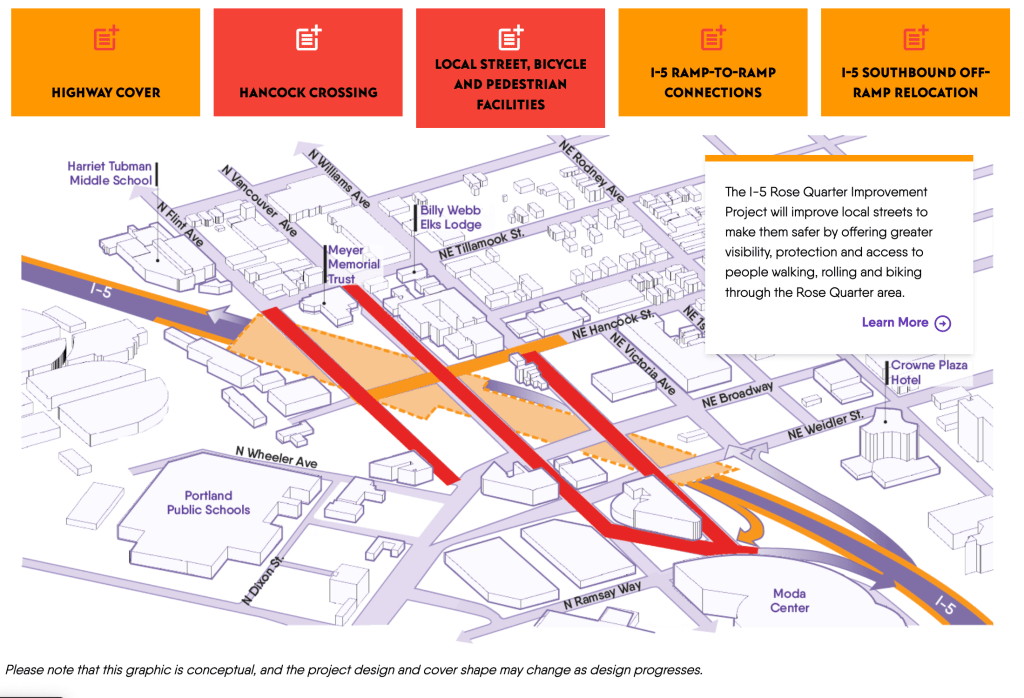

Since highway expansion/capacity projects are politically unpopular in Portland, ODOT has spent the last couple of years bending over backwards to brand this project as anything other than a highway expansion. The current project website lists five major “Project Features” on the main page – with an infographic showing a small slice of the project area. Let’s examine these.

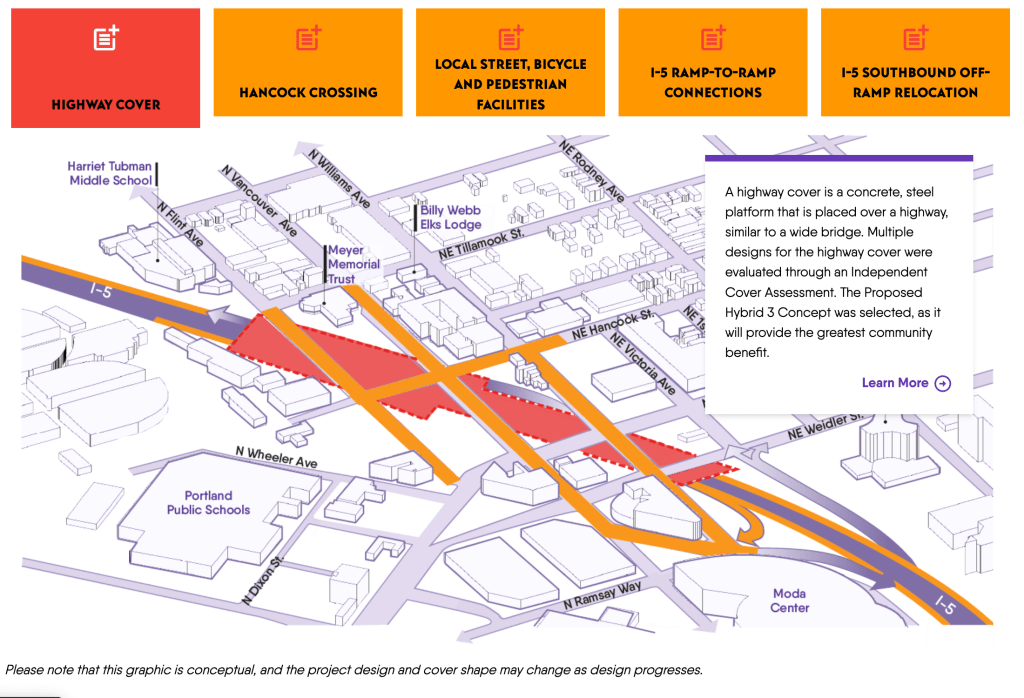

First, we have the highway cover; the keystone of the entire project. When I5 was built in the 1950s and 60s, ODOT acquired the right of way mostly via eminent domain or by lowballing property owners ($50 per parcel was common). As I touched on in my Sacking of Lower Albina post, the area affected was the (relatively) newly minted home of Portland’s Black community after the Vanport flood. All in all, ODOT acquired and demolished ~330 homes in the area with little to no compensation for the tenants. This highway cover is their way of trying to make up for it, but is it actually up to snuff?

The highlighted red sections add up to ~5 acres of added land, that will have a building height restriction of 3 stories (most likely – I am assuming ODOT will not elect to pursue a more expensive cover allowing for 5 story buildings). But even 5 acres is perhaps overselling things a bit, given the misshapen nature of the cover and the freeway entrance at Broadway still existing. ODOT demolished on the order of 90 acres for freeway infrastructure in the project area, so by my count they still owe the residents 85 acres of land – at minimum.

There are no firm plans for what will actually be on the freeway cover yet – but it seems unlikely that it will be just given away to the people (or their descendants) who were displaced by the original freeway. No doubt it will be some low-rise apartments with some guaranteed % of lower than 75% of the regions median income and a park or two. Which isn’t to say affordable housing is some bad thing to build, but maybe spending a full billion dollars on a freeway cap to put them on isn’t the best way to actually make enough to meet the need.

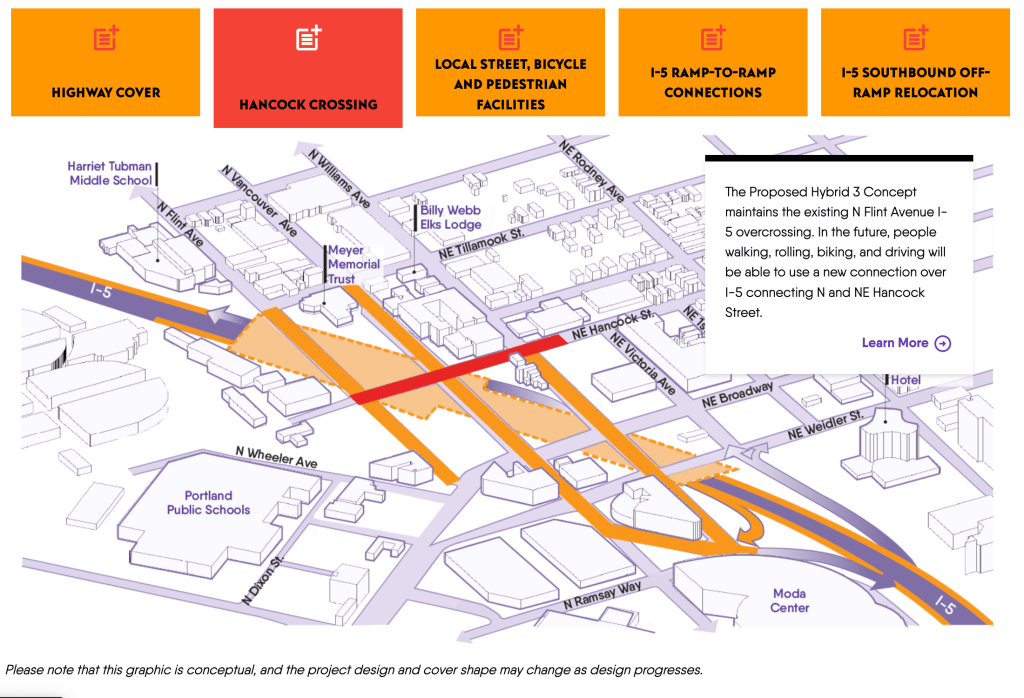

The second and third items are largely good in theory, although I will have to wait until the next environmental impact review comes out in October to see what’s really planned for “Local Street Facilities”. Right now, there are two different design updates (a 15% or a 20%.. whatever those mean is a bit lost on me). The 15% has absolutely horrible recommendations (closing crosswalks, adding more lanes, removing bus lanes, etc.). The 20% seems better, but was more technical and just much harder to wade through. Curiously, there are planned dedicated bike/ped facilities connecting the Hancock crossing to Dixon. I walk and bike through the area quite frequently, and had to do a fair amount of searching to even find Dixon (right in front of the PPS building). I’m very skeptical of the usefulness of this – a theoretical bike ride over the Broadway Bridge and up Williams wouldn’t use it, and neither would a reverse trip (unless major improvements are made to the corner of Dixon/Larrabee – especially since Larrabee is an old highway ramp).

Fourth, are the auxiliary lanes – which I’ve already discussed at length. But I think it is worth point out that the diagram shows the auxiliary lanes not really affecting the overall width of the roadway. This gives the average viewer the impression that there won’t be a serious roadway widening going on. In reality, the new auxiliary lanes will widen the overall freeway by about one-third throughout the project area (places with one existing auxiliary lane will be one-quarter wider, but that is relatively less of the project area).

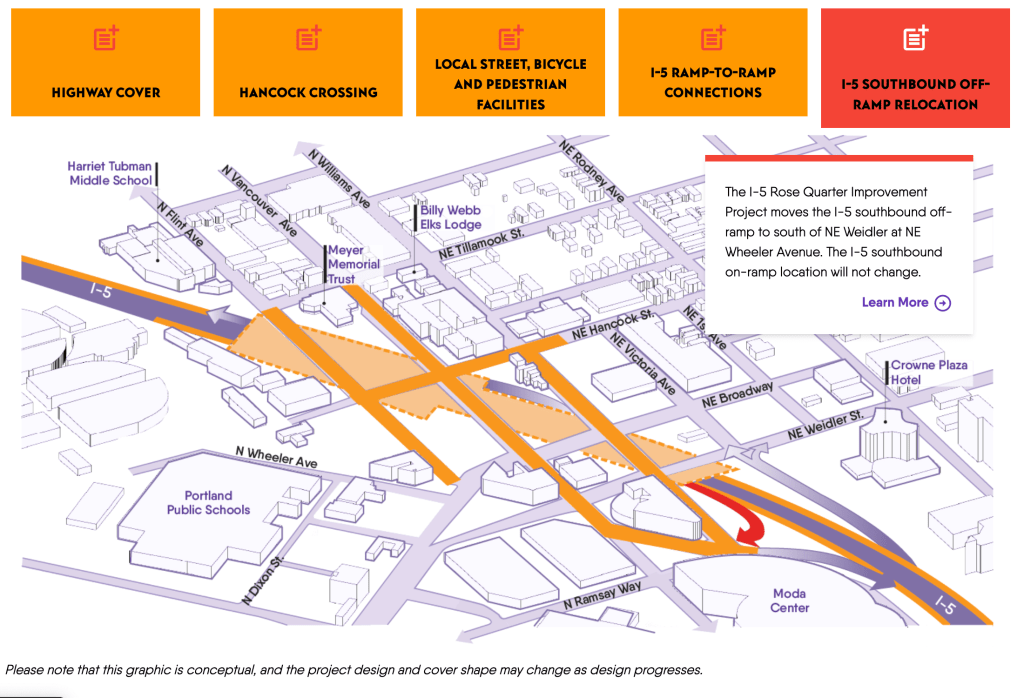

And finally we come to the off-ramp relocation. This is an absolutely horrible plan, and will make the entire area noticeably harder to get through on a bike or as a pedestrian. As it stands, the intersection of Ramsay/Wheeler/Williams and the I5 on-ramp is a huge pain for anyone heading north via Williams (basically anyone coming from downtown, or the Eastbank Esplanade). Adding a freeway off-ramp is going to make it so much worse – and not just at that corner. All exiting traffic heading towards Broadway will now have to turn up Williams to get there, which will certainly make it less attractive bike and walking route (and that’s not even getting into the proposal to turn NE Wheeler between the Moda and the intersection back to a two-way car road – rather than the current state of northbound bus only). Surely, the detour recommended by ODOT and PBOT will involve the new path at Dixon/Hancock, but this makes the trip from the exit of the Esplanade at the Steel Bridge to the corner of Williams and Hancock more than 50% longer – which is very bad to say the least.

ODOT’s stated reasoning for the off-ramp relocation is to “reduce interactions between vehicles exiting I-5 and people walking, rolling and biking along local streets on the highway cover”. If this can only be accomplished by nuking the connectivity between north and south Portland, I take serious issues with the “multi-modal” claims of the project. It’s a commendable idea, but if the real goal is reducing interactions between vehicles exiting I5 and pedestrians/cyclists, the best option is to remove the off ramp entirely – and nothing else comes close. Of course, this would reduce the “operational value” or something of the freeway, and might slightly inconvenience drivers so it’s a non-starter. Forcing long detours for people outside of cars is obviously better than someone having to drive an extra mile to park their car at the Moda Center!

Other Stated Benefits

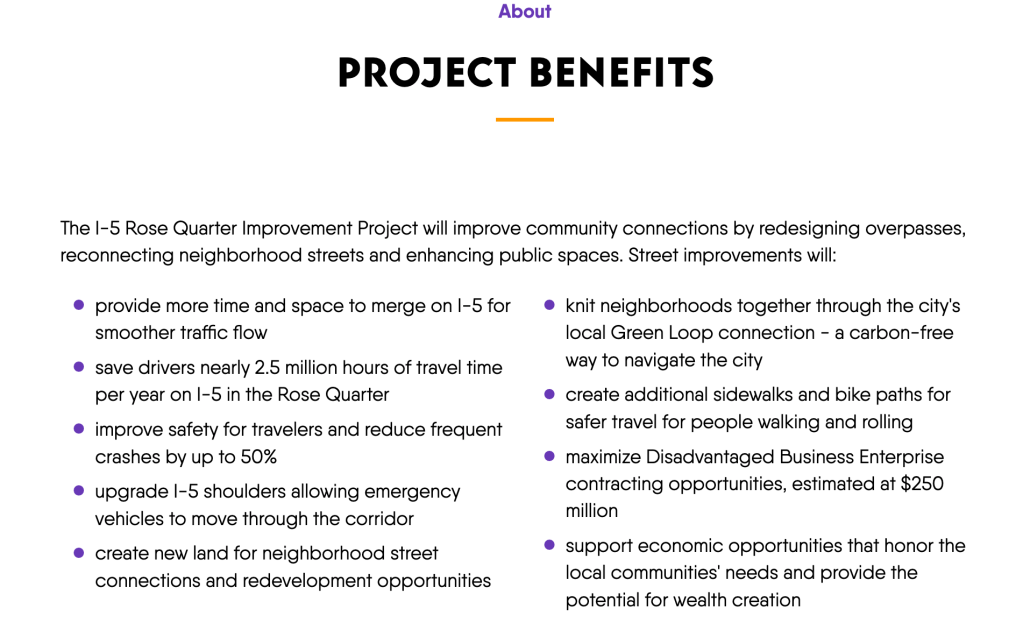

We’ve already touched on most of these points to some extent, but I want to dig deeper on what saving drivers “nearly 2.5 million hours of travel time per year” really means – since it’s very common to see language like this in freeway expansion proposals. I’ll try to state my assumptions as I make them, but a fair warning here – I’m just some guy.

2.5 million hours per year? Well heck that sure sounds like a lot – must be a good thing to shoot for! But let’s take it one step at a time here; what exactly does ODOT mean when they say “drivers”. Maybe you think of a suburban commuter, or maybe a trucker, or a down on their luck guy from the Midwest doing some soul searching in the great Pacific Northwest. While we can’t get that fine grained (yet), we can look at the “Detailed Traffic Volume Table” on the ODOT website to get a better idea of the both the total vehicles, and the distribution of freight vs. personal vehicles – and consider what factors are leading to this.

Looking at ODOT site ID #121 at the Holladay over-crossing (this is the Rose Quarter Transit MAX Stop as well, for reference) in that Detailed Traffic Volume Table for 2021, we see 114,543 average vehicles with 9.6% of those being Class 7 or greater (meaning four or more axels). In 2015, the earliest year ODOT has on the website, site #121 handled 122,600 with just 7.9% of those being Class 7 or greater. All in all, this means the Rose Quarter area handled ~4 million trucks in 2021 up from ~3.5 million in 2015; a 14% increase. For reference, the Portland Metro area grew by about 8% in the same timeframe. I am thinking the closure of the deepwater container port is a huge factor here, but not really a can of worms I feel comfortable opening (it has been functionally closed since about 2015 after the departure of Hapag-Lloyd).

Unpacking that little “2.5 million hours” figure a little more, with an average of 114,543 vehicles, 9.6% freight, and an average vehicle occupancy of 1.67 for personal and 1 for freight vehicles we end up with ~183,920 people per day going through that corridor. With a 365 day year, that pans out to a grand total of 2 minutes 14 seconds per person per day (note this is a very simplistic way of dealing with traffic dynamics, in reality the “time savings” are not uniformly distributed and most of the “savings” would be taken by cars in the “just before” and “just after” traffic times – but I think it is still a useful figure). Given the regular fluctuations of a typical commute in traffic, this is worth almost nothing. Google quotes a typical commute from Downtown Portland to Vancouver, WA via the Rose Quarter as taking between 28 and 60 minutes, spending a billion dollars to reduce that to 26 to 58 minutes is absurd.

And all of this is operating on the assumption that the project will actually accomplish the projected goals. American freeway mega projects have a long, long history of not accomplishing their goals of reduced congestion. The Big Dig in Boston cost almost $15 billion and made traffic worse. Adding freeway capacity is just not an effective long term solution – and while ODOT claims to know this, all of the top projects in the state are also freeway capacity projects. Which makes me think that they don’t actually know this – or that the politics of running a state DOT rely on policy makers who don’t actually know how to fix the problems they are dealing with.

The second claim with an actual number is “reducing frequent crashes by up to 50%”. This claim is on it’s face, so wishy-washy as to be meaningless. If anyone quotes “up to” instead of “at least”, they are being cheeky with what the end result actual will be. All this is saying is that a 50% reduction is the best possible outcome on just the freeway. Plus, given ODOT’s own data saying a 20-30% reduction in crashes should be expected from auxiliary lanes, I think it’s best to say this is being purposefully misleading.

So What About Economic Opportunity?

Three out of the nine stated benefits are in the “economic development and opportunity” lane. And while broadly speaking, economic opportunity is good, it’s inclusion here merits a little further investigation. First, what are “Disadvantaged Business Enterprise contracting opportunities” anyways? Well it’s just a USDOT program for trying to make amends to communities previously harmed by things like the Interstate Highway System. But it primarily applies (as far as I can tell) to USDOT related contracts – so in this case, construction, engineering, and the like. And while I would prefer a diverse set of contractors, it’s hardly a good justification for a project. The main issues with the Interstate Highway System have not been the demographic profiles of the contractors hired.

I’ve touched a bit on the size of the highway cover, but at about 5 acres (out of the 90ish bulldozed in Albina to build I5), I was curious about the footprint of parking lots in the nearby area. In just the area bounded by I5, Multnomah, MLK and Broadway there are 9 acres of parking lots. Spending upwards of a billion dollars on five acres surrounded by parking lots and freeway is just not a great investment in my opinion.

And the final piece of the economic puzzle is probably the hardest to quantify, unpack, and really understand in any quantitative way. “Supporting economic opportunities that honor the local communities needs” is certainly a good goal, but does this project actually provide that in any substantial need? And who is included in “local community”? Is it people who live in the neighborhood now, or those does it include who have been priced out (or otherwise displaced) via gentrification and rising cost of living? This is another “benefit” that seems a little nebulous, and I am unsure as to how the project specifically provides the “potential for wealth creation”. Typically, American inter-generational wealth has been built via homeownership or entrepreneurship and I just am not sure that this highway project meaningfully provides any extra opportunity via either of those. If ODOT were serious about wealth building, providing funds for the subsidization of housing via down payments or rate reductions for folks affected by their long history of freeway building would be a much better way to build that wealth.

When it comes down to it, the economic arguments are not very compelling to me. At a regional level, the project won’t really move the needle on travel times per ODOT’s own claims. For freight in and out of the Portland region, it is insignificant compared to the Port of Portland re-opening deepwater container operations. And at a local level, it just doesn’t really strike me as the most effective way to invest in the people who live in the area.

Putting it All Together

Given all the shortfalls, hand-wringing, and extreme cost it’s probably easy to see why I think this project is a sham. But the real issue is philosophical, rather than a failure of numbers and politics. When the state of Oregon funds projects like these, it continues the time-honored American tradition of only spending public money on (more or less) solely personal automobile infrastructure. And the continued centering of the personal automobile in transportation policy is the real issue I take with any freeway project; chaining mobility at a local, regional, and state level to a car just sucks. Cars are a black hole, sucking in your hard-earned freedom dollars and spitting out fumes, rubber particulates, and congestion.

This is felt most acutely, like all things in America, by people with the least financial resources. In 2019, the US Bureau of Labor and Statistics reported that the poorest quintile (bottom 20% by income) spent a whopping 37% of their income on car-related expenses ($4,581 out of $12,236). This is no accident, while the American economy as a whole is more or less structured to rob the poorest among us via payday loans, predatory banking, and other debt traps; car expenses are the real silent killer. Predatory car lending is endemic to poor neighborhoods, leading an endless cycle of financing and repossession when the terms of the loan aren’t met. And given that the poorest neighborhoods often see the worst transit service, the most dangerous bike infrastructure, and are continually pushed further to the urban fringe cars are often the only mobility option.

And ultimately, freeway projects do little, if anything, to help the people who need it the most. The Rose Quarter Project further cements the car as king, at a time when we need it least. The $1.5 billion would be far better elsewhere, and ODOT’s failure to recognize this makes Portland a worse place to live.

Leave a comment