After a brief interlude to complain about the Interstate Highway System, let’s wrap up our discussion of high speed rail in the Badger State. Each of the segment discussed have gotten more complicated, and creating a route capable of high speed service between Madison and the Twin Cities is no different. There are no lightly used branch lines to take advantage of, and it seems unlikely that there is any hope for a nationwide Shinkansen style system being stood up.

But fear not, this is no dead end. There are still two different main line routes that can be taken between the two cities*, but creating a way to utilize them is no easy task. But let’s consider the history of a place with a similar cultural background that managed to consolidate a few disparate lines for passenger service from legacy operators.

*you could throw one more in (the old Milwaukee Road branch to Prairie du Chien), but it is a fair bit longer I won’t be considering it

The Birth of the Northeast Corridor

In 1970, Penn Central went bankrupt. The merger of two of the largest and most profitable railroads of the Gilded Age (the Pennsylvania and the New York Central) was short lived and a fascinating episode in corporate failure. But that’s a topic for another time, the important thing to note is that a requirement of the merger was subsuming the New Haven as well, thus giving a single railroad ownership over the entirety of what is now the Northeast Corridor.

The bankruptcy of Penn Central led to the creation of Conrail, a government owned national rail carrier centered in the northeast which directly operated lines previously owned by Penn Central, Erie Lackawana, and the Reading Railroad (among others). As rail traffic recovered in the Conrail era after the crises of the 1970s, passenger service on the newly minted Northeast Corridor on Amtrak also boomed. If a private operator, mostly concerned with freight, had still owned the rails it’s unlikely that this boom would have been possible. But since Conrail was functionally owned by the same people who owned Amtrak, it allowed for a straightforward agreement in which Amtrak would own and operate primarily for passenger service, with trackage rights going for freight service.

Plenty of rail operators still have trackage rights, but it’s significant that ownership of the most direct route between all of the largest cities on the East Coast was transferred to Amtrak, rather than a freight operator. Conrail ultimately was broken up in the late 90s, sold off to CSX and Norfolk Southern – in what I can only describe as a tragedy – but the legacy of public ownership remains. Because of this foresight, more than 2,000 passenger trains a day operate on the corridor and Amtrak makes a profit running these trains – despite some quirks inherited from the legacy of multiple operators like different electrification schemes on different parts of the route.

Why Does This Matter?

As I’ve talked about previously, the benefit of high speed rail isn’t just the speed, it’s about control. It’s no coincidence that Amtrak’s most profitable, popular, and highest speed route exists in a place where they have direct control. Yes, it helps that the Northeast contains a myriad of dense legacy cities but as we’ve seen the Midwest has its fair share of population corridors as well. Chicago to Milwaukee is as good an analogue as any to “small New York” to “small Philadelphia”. Which makes the Twin Cities small Boston, which I think is fitting too.

Conrail may not have been designed with the purpose of segregating rail passenger and freight service in pursuit of a high speed line on the East Coast, but that is its primary legacy (well that and abandoning the Pennsylvania Railroad Pittsburgh to Saint Louis main line). So let’s imagine a Conrail-style scenario in Wisconsin – but instead with the goal of creating dedicated passenger* and freight lines

*it’s worth stressing that “dedicated” is meant in the same sense that the Northeast Corridor is dedicated – local freight still has slots to operate, but passenger rail is the priority

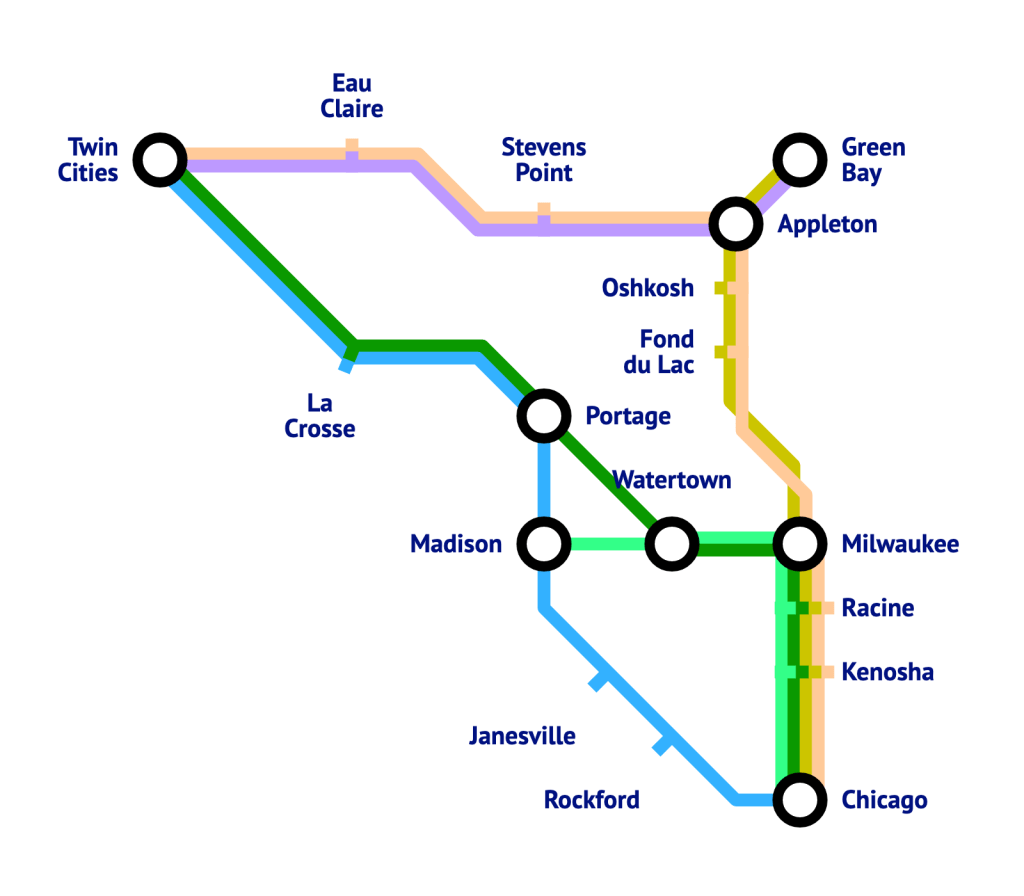

Conrail Wisconsin

Here we have a plan for freight service consolidation (in yellow), with a handful of lines identified for either primarily passenger service (dark red), or some with substantial passenger service along with freight (orange). The lines in orange represent areas with either less hypothetical service (like a regional line to Middleton), or where no reasonable parallel exists but the right of way is wide enough for two or three tracks which could be dedicated to freight or passenger trains as needed. Also worth noting, that some currently abandoned lines would be rebuilt – most notably between Milwaukee and Green Bay via Sheboygan, to offer parallel freight service between the cities away from the passenger priority main line in the Fox Valley area.

The primary difference between my plan and the current iteration of Amtrak’s Connect Us relates to Eau Claire, with my preference to dedicate most of the former Chicago & Northwestern mainline to freight service (to make up for dedicated passenger service on the old Milwaukee Road) and instead routing trains from the Twin Cities to Chicago via Eau Claire over the former Wisconsin Central/Soo Line route further north. I see this as a beneficial choice for a few reasons, but mostly it relates to the classic story told about the Empire Builder in Montana.

See in Montana, part of the justification for retaining the Empire Builder (serving far north Montana) rather than the North Coast Hiawatha (serving the major cities) is that there aren’t nearly as many transportation options. The same is true in northern Wisconsin, with poor airports and a lack of bus and freeway service that the I-94 corridor has. Megabus is the only option, and given that the company has recently cut huge swaths of their system it’s hard to feel good about the prospects of intercity travel in the region.

This would leave Sheboygan as the largest city in the state to not be served by passenger rail, and includes every city over 50,000. It also has the benefit of only really using four different freight main lines, parts of which are already state owned between Milwaukee and Fond du Lac, and between Janesville and Madison.

And while two of these lines – the Canadian National (neé Soo Line) line from Stevens Point to Fond du Lac, and the Canadian Pacific (neé Milwaukee Road) line from Milwaukee to the Twin Cities are quite busy, this is where the freight consolidation comes in to play. Since the current Union Pacific (neé Chicago & Northwestern) main line is somewhat lightly used, there should be excess capacity available to make up for the loss of through traffic on the old Milwaukee Road. And by rebuilding parts of old branch lines in far northern Wisconsin, a secondary main line between Duluth and Chicago could make up for lost capacity on the current Canadian National line.

What’s Stopping Us?

Is it likely that any of the major rail companies would agree to this? Not right now, no. But that isn’t the point here, because the interests of these companies is not even remotely in line with the median American. They are rarely even in line with their customers, as they prefer to abandon or spin off branch lines to newly spun up class III companies rather than operate them even when they are profitable. And of course, the issues facing the freight rail industry relating to workforce reductions, derailments, precision scheduled railroading, and poor maintenance practices mean that we really shouldn’t take what the executives of these companies have to say all that seriously. Instead, we ought to listen to rail workers – who have been calling for national ownership of the rails for a long time.

Suffice to say, “Warren Buffet wants to make more profit” is not a compelling reason to leave our railroads in their current state. And really, that’s what the rail companies argument is at heart. Because serving customers is evidently not high on their list, and neither is taking good care of our nations great railroads. That pretty much just leaves “making a profit for execs and shareholders” – not something we should gamble the future of something so vital as rail transportation in the US on.

And of course, it’s Wisconsin. The reality of the current political climate might make high speed rail an uphill battle, but that shouldn’t stop us from dreaming. A well articulated plan about high speed rail is necessary to garner support around specific benefits – like serving parts of rural Wisconsin with no current choices for intercity transportation. And remember – this plan is just a starting point for a coherent network.

Even in “red” parts of Wisconsin, there is a longstanding tradition of advocating for passenger rail to return. Getting folks to see the Packers, and to visit quaint small towns, all without the need for another DUI is something that has the possibility for widespread bipartisan support. All it needs is a coherent plan that doesn’t break the bank.

Financing

Of course, none of this would be free. Good high speed services requires electrification, and ~1,000 miles of track being electrified would not be cheap. The “typical” cost for electrifying is $1.5 million to $2.5 million per mile, so this part of the project would probably run close to $2 billion. Additionally, new rolling stock, signalling, and a host of other associated projects – like eliminating grade crossings, straightening curves, building stations, and double or triple tracking certain sections.

Given the collaborative nature of the project, with huge benefits for Minnesota and Illinois, funding could also be sourced from those states. And of course, the actual operation of the services would likely fall to Amtrak. This would make it easier to get federal funding for at least the rolling stock for the project, although given that the federal government recently gave Brightline West like $3 billion to construct a line from Rancho Cucamonga to Vegas there would hopefully be opportunities for cost sharing.

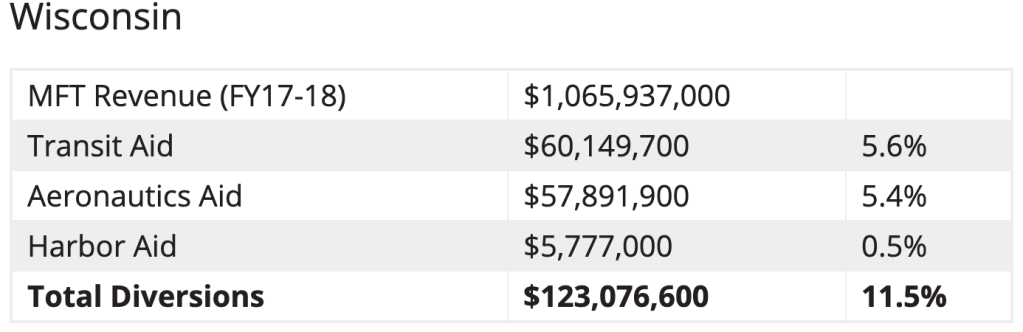

Anyways, the ways Wisconsin pays for most of its transportation projects are gas taxes and other fees associated with driving. Luckily, there is nothing stopping the state DOT from disbursing this money to non-highway related projects (as shown in this brief that is presumably critical of spending gas tax money on other projects). Raising taxes isn’t typically popular, but likely necessary to pay for something like this.

Additionally, issuing bonds would be wise – since passenger rail service has a natural revenue recovery scheme built in with tickets. How much money could be bonded depends heavily on future ridership, but luckily we have a fairly frequent conventional speed rail to compare to. Amtrak’s Hiawatha has captured about 1% to 2% of the land travel market between Milwaukee and Chicago (AADT on I-94 is 90k to 100k, Hiawatha sees about 1,500 passengers a day, and private car/truck split is ~85%/15% in Oregon [no data from Wisconsin available]). I find this to be impressive, given that there are only 7 trips (6 on Sunday) and the average travel speed is about 60 mph.

If we manage a service pattern with hourly trips (plus a few extra at peak) for 30 trains a day, with operating speeds twice as fast, I think it’s fair to say that the rate would be closer to 10%, and given that Amtrak carries about 14% of intercity trips in the northeast (2003) this seems like a fair guesstimate. 10,000 passengers a day, with 300 to 500 passengers per train would be about 30 trips a day. Financing just this segment on bonds requires a bit more guesswork about tickets, but if a $2.50 surcharge were added to pay for bonds that’s about $9 million/year. At 5% return over 10 years, that’s a total capacity approaching $2 billion, though because this depends heavily on our somewhat optimistic 10,000 passengers/day – a number I imagine a bank would be somewhat less enthusiastic about. But even at current ridership levels, a $2.50 surcharge could still create an upper bonding limit of $750 million – surely enough to at least pay for purchasing the Chicago – Milwaukee right of way and electrifying.

Still, it’s a useful heuristic and using bonding that is paid for by ticket sales to finance a high speed rail scheme is an attractive option. We could even create a government authority responsible for issuing these bonds, and appoint a powerful individual to it who oversees disbursements of funds and a whole host of other things, and give it the authority to issue new bonds as it sees fit. That would have the benefit of creating an independent authority that could manage the system outside of political squabbles, but has the downside of being exactly what Robert Moses did with the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority.

So maybe we should avoid creating a Robert Moses of high speed rail in Wisconsin, but the point remains that money creates political power and if we want a successful high speed rail project we need to give it money. If we were to create a Tristate High Speed Rail Authority, and gave it the power to issue its own bonds, we would at least need to make sure whoever runs it is actually accountable to public interests. It’s all about balance.

Closing Thoughts

This, more than any other post about high speed rail in Wisconsin, is on the speculative side. Since my preference is to utilize existing rail corridors, there comes a time where it is necessary to consider freight policy and how it will relate to passenger service. Ultimately, I find the lessons learned from Conrail and Amtrak in the 1970s to be illustrative, and a loose guide for how consolidation can lead to better outcomes for both freight service and passenger service.

Even if this scheme relies on railroad nationalization of sorts to be feasible, it’s worth planning for a future world where that is a possibility. Because to most people, railroad nationalization is a fringe idea that wouldn’t really directly benefit them or anyone they know. Using nationalization as an opportunity to build high speed rail services at the same time gives the policy legs of its own to stand on.

And while free transit is something that advocates talk in circles about, ticket revenue is a source of income that can and should be used to expand service. Because improvements to infrastructure almost always induce more demand for that infrastructure, bonds for improving rail service based on revenue from a surcharge on tickets should be a self-fulfilling prophecy – one where the bonds themselves end up creating more demand.

But none of this will happen without some semblance of a political movement, and it won’t happen without people working for it. I’m not sure who in Wisconsin is actively working for these outcomes, if anyone is. If you know anyone, share this with them and tell them to get in touch with me, I’d love to talk shop.

Thanks for reading and going down a rabbit hole with me. I’ll be writing more about rail policy in the coming weeks, with my next focus being on my adopted home of Oregon.

Leave a comment