For the last few weeks, Los Angeles has been on fire. Driven by the combination of a dry winter and an intense bout of Santa Ana winds, huge portions of urbanized Los Angeles have burned to the ground. Preliminary estimates over a week ago pointed to more than 5,000 destroyed structures, a figure that is sure to grow over the coming weeks. But how much of this has to do with climate change, and how much of it has to do with the fact that wanton disregard for the fire ecology of Southern California? And what on earth should we do about it?

Fire and LA

Los Angeles, like much of the US, was previously subject to routine burning. Native Americans of the area, such as the Tongva, used fire as a means to manage undergrowth, drive game, and improve pasture on a regular basis. The result is that the chaparral endemic to the pleasant, but dry, climate of Southern California had little chance to establish itself in the dense thickets that typify the region now.

The arrival of Spanish explorers and missionaries, and, later, Euro-American settlers, profoundly altered this regime of land management practices. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that the US Forest Service embarked on its journey of attempting to fully suppress wildland fires in the US. In Malibu, the Pacific Palisades, and other areas that lie between the Santa Monica mountains and the sea, this has meant catastrophic fire at regular intervals. The Santa Ana winds rush through the narrow canyons of the Santa Monicas, and the bone-dry, aging chaparral barely needs a spark to ignite. From 1928 to 2018, at least 30 separate fires burned. And unlike in pre-settlement times, where fires burned regularly and kept the total fuel supply low, fire suppression in years without major fires means that the major ones readily become catastrophic.

Somewhat shockingly, as Mike Davis outlines in his classic piece, The Case for Letting Malibu Burn (a chapter in the must-read Ecology of Fear), the result of this catastrophic fire pattern has been to “[stimulate] both development and upward social succession”. Displaced bohemians, unable to foot the bill for the massive task of rebuilding gave way to the Hollywood Stars and other members of the nouveau riche who could. Thus, “each new conflagration would be punctually followed by reconstruction on a larger and even more exclusive scale as land use regulations and sometimes even the fire code were relaxed to accommodate fire ‘victims.’“

This last point will come to a head later.

The Changing Climate

Evidently, climate change plays a large role in disasters of this scale, but climate science is not my forte. I’ve read the same headlines as you about more intense drought, more severe precipitation events, and the cacophony of other interlocking issues. It’s clear that the degree and timing of this wildfire event is unusual, even unprecedented – with only two other winters following wet years beginning so dry. The dryness immediately after wet years is particularly problematic, as it means more fuel is added to the fire.

So when I hear the refrain “nothing could have been done to prevent this”, or “no one could have predicted this” when there’s a whole host of decades-old research that predicts this, and a whole Indigenous history of the region outlining methods by which these conditions (of intense, aging, chaparral growth) can be avoided, I raise my eyebrows. There was no one forcing Los Angeles to refuse to foreclose on the Malibu Ranch property in the 1940s, and there was no one forcing us to continually rebuild in some of the most fire-prone areas in the world. Oh, and we could do something about climate change too. It’s just a simple matter of recreating the entire economic structure of the world .

Hazard Zoning

But outside of a climate-oriented social revolution, the short term solution to the problem of wildfire destruction is potentially something as “simple” as hazard zoning. Put shortly, preventing development in areas with a clear vulnerability to fire. Rather than continually developing and redeveloping Malibu, we could instead create a natural, publicly accessible area managed in harmony with the fire ecology inherent to the area.

Of course, it all sounds so simple and easy when you put it that way – but that involves preventing some of the wealthiest and most powerful people in Los Angeles from getting their way. And if there’s one thing you should know about Southern California, it’s that things like that don’t really happen. But we should not stop at Malibu – indeed, it’s simply the place most likely to garner headlines when it burns. There are countless examples of developments – entire cities – situated in disaster zones. Can we expand this idea to them?

The Hazards of Hazard Zoning

To identify areas that are most prone to natural disasters – fires, hurricanes, flooding, earthquakes – you name it, we first need to consider what this would entail. Evidently, some government agency would create a map to show which regions are most likely to be affected by some kind of natural disaster that would threaten the solvency of the insurance market. Next, some kind of relative scale should be introduced – let’s use green for “suitable for development”, and then a yellow-red gradient towards “not suitable for development”.

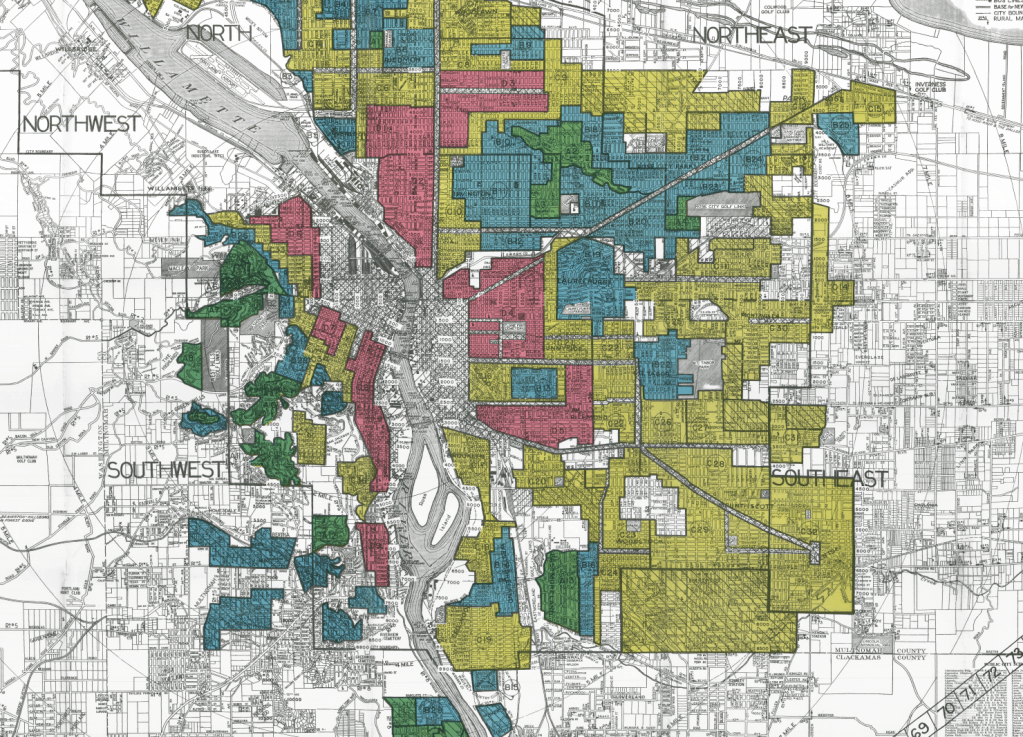

Now if this description sounds a lot like a redlining map, that was intentional. In the 1930s, the Federal Government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created a series of maps outlining investment risk in certain areas. Of course, it was the 1930s, so a primary “negative” factor is the presence of Black people, as well as any other so-called subversive race. The net result of these maps was that home owners in redlined areas found it much more difficult to secure financing for repairs or other improvements, and new residents had difficulties securing mortgages. It went hand-in-hand with policies designed to disenfranchise racial minorities – but specifically Black Americans – from the mortgage and lending markets.

Of course, these days we rightfully feel strongly that this was wrong on its face. The redlining maps were a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the reduction in credit caused the very rot and dilapidation the maps alleged to care about. If we aren’t careful, hazard zoning risks falling in to the same trap. If the federal government creates a map of areas not considered suitable for development, redevelopment, or other uses, it will necessarily mean destroying the ability of those who live there to seek insurance policies or ensure financing for continued maintenance. In a country already facing an acute housing shortage, can we displace the millions of Americans who live in the floodplains, liquefaction zones, and fire belts our predecessors were too greedy to resist building on?

The short answer is no, though the long answer is that we may not have a choice. To bridge this gap, we need sensibly crafted policy and a real alternative to our current market-oriented housing world. Let’s take a look to see what we may find.

Market Forces Mean Rich People Win

Issues with redlining extend beyond the overt racism. While that’s obviously the proximate cause of the harm, the vicious cycle that the federal government created is wrapped up in the fact that insurers and lenders refused to deal in those areas – not just the reasons why. And the lasting harm of redlining – even some 60 years after the formal conclusion of the Civil Rights movement – has just as much to do with the predatory market forces spawned by government policy as it does to do with the policy itself. In short, if we want to have good land use (and housing) policy in a climate-threatened future, we need to think about more than just the first-order effects of the policy.

Absent any discussion of the economics of hazard zoning, we should understand the effects to be as follows:

- Government policy dictates the ways in which development can occur in climate hazard zones. Some of these areas contain existing developments.

- The government deals with existing development either directly by mass removal (extremely unlikely), or indirectly by denying financing (more likely).

- The value and resources afforded to these zones is massively reduced, leading to an exodus of any remaining of the well-to-dos.

- The working poor and any others who have few choices will resort to these less desirable areas.

- Natural disasters come all the same, and poor residents experience a disproportionate impact.

The classic example of this is New Orleans. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the Urban Land Institute (ULI) crafted a plan which outlined three investment areas corresponding to the extent of the post-storm floods (with Zone A being the most affected and Zone C being the least). In Zone A, extensive amounts of land were to be taken in the name of flood protection. Of course, New Orleans is basically all built on filled wetland so the need for more robust flood protection is absolutely there. The issue is that Zone A was disproportionately poor and Black, and the condemnation of these areas would burden the same people who bore the brunt of the Hurricane.

The denial of credit to flooded areas would have amounted to a death knell, and the entire plan centered around the presupposition that there wouldn’t be enough money to rebuild it all, so the city must pick and choose. Inevitably, the ULI made the same choice land profiteers the world over have – build amenities for the wealthy and middle class, and leave the poor to rot. The plan as crafted would have directed investment to places where it surely was needed, but in part by denying to places where it was needed more. It was redlining by a different name.

The difficult part about this is that the plan has a great deal of good logic. At some point, a discussion needs to be had about where should or shouldn’t be developed as it relates to areas prone to disasters, especially in New Orleans. But the choice always seems to be to sacrifice poor neighborhoods to save the rich ones. No matter how dire the need may be, this can never be an acceptable course of action.

A Return to Social Housing …

Homelessness is up 18.1% nationally, and we are already staring down the barrel of only the rich being afforded the luxury of a roof over their heads. Once upon a time, our nation addressed a housing crisis of similar scale – borne out of the Great Depression and WWII – with intense action. Of course, the following suburban boom and the racist practices of the FHA to deny non-white (but especially Black) families credit are infamous – but this was also a time where government commitment to social housing was high.

Of course, the projects built were ultimately deemed to be massive failures. But is this a fundamental result of social housing, or was it simply a result of poor implementation? I lean toward the latter. There are many examples of successful social housing – like in Vienna, where the city government directly owns 25% of the housing stock. Evidently, a cursory bit of research will reveal a lot of success stories in Europe, and this is no accident. Rich countries in Western Europe didn’t retreat from their mid-century commitment to a more equitable society to the same degree that we did here in the US.

It’s easy to throw out Vienna as an example of how successful socialized housing can be, but it’s worth considering how Vienna managed it. In short, the “Red Vienna” government of the interwar period took advantage of a huge crisis in the wake of the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with an aggressive building strategy. The combination of leftist politics and a unique historical moment yielded a lasting, permanent affordable housing market which is truly remarkable, even in Europe. The buildings were designed with constituents best interests in mind, rather than by paternalistic master planners, something that speaks to the bottom-up nature of the government ideology at the time.

… Means a Return to Democracy

In an old video debating the merits of railway nationalization, the leftist YouTuber Unlearning Economics outlines a specific problem with railway nationalization in the UK. In short, when nationalization occurred in the wake of the Second World War, the same people who managed the private railways ended up heading the soon-to-be dysfunctional British Rail. When privatization occurred in the 1990s, it was the heads of British Rail who ended up running the private companies again.

Essentially, the problem with railway nationalization is that the top-down, centralized structure is stifling and bad for workers. Nationalization failed to meaningfully change this, and so did re-privatization, so the net result is massive labor unrest and a dysfunctional system. It doesn’t really matter who runs the system (corporate overlords or government overlords), if those with the greatest stake in the process (workers, residents, etc.) lack the power to effect change, the system will not be responsive enough to satisfy the needs of those people. Post-war US public housing suffered from this same fate – with sprawling, underfunded bureaucrats being unable to respond to the needs of residents.

In my estimation, Vienna’s social housing model succeeds at least in part because it bucks this trend. Of course, it is centrally managed and planned, but the metrics by which it is done are essentially democratic. High income limits, the fact that residents are not pushed out if they earn more money, the expansive, multifaceted nature of the system (including subsidized co-ops and directly owned buildings), and the transparent allocation criteria are all factors in this. And since so many Wieners hold the system in high esteem and have a direct stake in its continued success, it is continually reinvested in.

A core tenet of social democratic (or socialist, if you don’t balk at that term) values is that freedom extends into the economic realm. If people do not have the resources to meaningfully participate in society, they can hardly be said to be free – regardless of the legal commitments that may exist. In a housing market dominated by market forces, rich people have the freedom to live wherever they please, while the poor are forced to be where the rich don’t want to be. Moving beyond our current economic model means granting freedom to millions of people unable to live happy and fruitful lives who are currently crushed as cogs in the machine of an inhumane system.

Strengthening the political and economic power of the working classes is a key point in preserving democratic structures. In a country with a worrying trend towards authoritarian rule, it’s worth keeping this in mind. We need to solve the climate crisis, but we cannot do this justly without a democratic process in which we all have a say.

Looking Forward

Eventually, climate change will force our society to reevaluate that, and implementing hazard zoning in the former hovels of the rich and famous will hopefully become significantly easier. It’s clear we are a very long way from there. Even now, as the fires rage, California governor Gavin Newsom has waived existing regulatory requirements for rebuilding in wildfire affected areas. Faced with a climate catastrophe, the physical manifestation of the corporate wing of the Democratic Party reflexively sides with wealthy, landed interests over common climate sense. Refusing to pay lip service to the idea that parts of urbanized Los Angeles may not be suitable for intensive human development is quite literally playing with fire.

But when this day finally comes, and we realize that it’s a fool’s errand to permanently inhabit the leeward slope of the Santa Monica mountains, the structure of our society will not be able to save the working class communities endemic to the floodplains, fire corridors, and liquefaction zones in our major cities. Malibu may sink beneath the sands of time, but the wealthy Angelenos will establish themselves elsewhere with little difficulty. Can the same be said of their working class compatriots in San Bernardino?

Ultimately, to judge our success in mitigating the climate crisis we will have to analyze the impact on those in our society who we have pushed to the margins. If we can only manage to stem the rising tides for the rich and famous in their ivory towers, while leaving the working poor to languish in the toxic lagoons of ages past, it will be impossible to judge it as a success – even if the crisis is abated.

Thanks for reading – ’til next time.

Leave a comment