If you’re like me and you follow transit news in Portland closely, you’ll have been following along with TriMet’s 82nd Avenue Transit Project. Preliminary stop locations have been released, along with some additional information. Some of this is very interesting – like how the 72 is being rerouted to (presumably) end at Parkrose TC, while the FX route will terminate at Cully after traveling up 82nd from Clackamas TC. I had started a whole spiel about what the fate of the Killingsworth leg of the 72 would be now once the Cully terminus of the FX route was announced, but this feels like a moot point now (though the impact of loss of frequency along that leg is worth considering).

But for the most part, the proposal is alarmingly milquetoast. The ongoing safety project of enhanced medians will preclude a center running busway (not that anyone ever advocated for that), and instead the most right of way treatment we can hope for is the occasional BAT lane (business access and transit). On a road like 82nd, where essentially the entire route is curb cuts for parking lots, even a full corridor side running bus lane would be just partially effective if right turns are allowed. There’s basically no chance of even this though. In the ongoing 15% design comments, TriMet essentially states that intersection area BAT lanes are the major consideration. This tracks closely with other small-scale projects like Rose Lanes that seek to alleviate bottlenecks in minimally invasive (to car traffic) ways.

This Isn’t BRT

Even if the FTA is funding this project as if it were bus rapid transit (BRT), it simply is not. The primary feature that makes or breaks BRT is a dedicated right of way – which is classically a center-running alignment along a major road.

Other features (off-board payment, level boarding, and signal priority) are great and necessary features, but without a dedicated right of way, BRT is just a bus. Rapid transit systems operate on dedicated rights of way, and that is the thing that distinguishes them from buses or streetcars/trams. The FTA has been ignoring this since at least 2009, and instead focusing on the secondary features (like branding, station amenities, and higher capacity vehicles).

And I know I’ve talked about this at length before, but I find extraordinarily frustrating that the FTA has such minimal requirements for funding BRT. In this 2017 Oregon Business article about the Division Transit Project, I’m struck by how willing everyone is to just throw out any semblance of “rapid transit” from the discussion. Saying that “transit experts don’t care what people call it, as long as it works” may be true to some extent, but I have a deep sense of frustration that we spend $170M on a transit project whose major benefits are just one more bus an hour, nicer shelters, signal priority, and longer stop spacing.

All of these can be implemented without a major capital project. So what’s the point of even the project? On Division, there were tons of ancillary justifications as it related to pedestrian safety . And yes, of course those improvements benefit and improve the transit environment, and serve to make bus riders lives better in the short and long term. But if you’ve walked Outer Division since the FX bus came to town, you’ll know that it’s still horrible. Less horrible, sure, but still horrible. An actual BRT could have done more to improve pedestrian safety than the project we got.

Does It Matter?

Jarrett Walker says in that same article that “in the end, what matters in transit is getting people places sooner.” I concur, but this ultimately is why pseudo-BRT is a failure. While it’s true that the FX2 is faster and more frequent* than the 2 and 4 that preceded it, it’s also slower than an actual BRT service would be along the same corridor. Travel time savings on Division amounted to 10% to 15%, while the actual BRT project on Van Ness in San Fransisco led to a 36% travel time saving.

*more frequent in the off-peak, generally less frequent in the peak hour. Though most of this lesser frequency in the peak hour is Covid transit commute loss related, and is probably fine.

Of course, you don’t need me to tell you that doubling an improvement is good. Sure, the Van Ness project cost like 5 times as much per mile and was in planning for the better part of 30 years but that’s more of a “San Francisco is an insane place” story than anything else. But the 49 gets eye-watering ridership numbers as well. 35,000 riders a day on a 7 mile route versus 8,100 on a 15 mile route is nearly 10 times as many riders per mile. I’d chock that up to San Francisco being way denser and more transit-reliant than Portland, but the 49 has seen upwards of 40% in ridership gains since 2019, while the 2/FX2 has seen a 15% drop.

It’s difficult to compare anywhere to San Francisco, but the huge ridership gains along Van Ness – even in an environment where transit ridership is still down – illustrate why we should not be too quick to dismiss the rapid transit aspects of BRT. Faster travel times matter, but relative changes can be misleading. A 15% travel time improvement that goes from “very slow” to “pretty slow” is less useful than a 10% travel time improvement that goes from “pretty slow” to “reasonable”. I think that the FX2 falls closer to the former than the latter, and based on what I can tell from the 82nd plans I’m expecting more of the same.

Regular Buses Can Be Good

When we were in Lugano last summer, Olivia and I rode the bus all over the place. Of course, some of this was ideological – I’m a bus rider through and through, there was no way we would have not ridden the bus. But it was also practical. Lugano isn’t a sprawling metropolis by any means, but the walk up the hill from the lake to the places we stayed was not appealing after a long day of arduous relaxation.

While there were some annoyances with riding the bus (namely, the final trip of the night being around midnight), each stop had a shelter, bench, and ticket machine. Most of the buses were articulated, at least for the core routes, and the buses ran almost exclusively in mixed traffic. While car access is generally lower in Switzerland than the US – two-thirds of Swiss households own a car versus 90% of American – it seems that this type of service is enough to get a quorum of regular schmucks who ride the bus over there. So it’s been invested in, and not everyone owns a car.

Speed has a lot to do with the bus being attractive as well though. Let’s consider speed relative to driving plus parking. It’s an 11 minute bus ride from Breganzona Posta down the hill to Lugano Centro, compared to a 9 minute drive. Surely once you factor in parking in the dense core of Lugano, the bus is just about faster. My commute downtown is a similar distance (about 2 miles), and has a comparable bus travel time of 11 minutes. Does the two minute difference in drive time make a difference?

In the narrow sense, probably not. Very few people are checking drive time versus transit time for a given trip and making a rational decision. But in the broader scheme of things, the gap between transit travel times and car travel times should be understood to be a proximate cause in relatively poor transit ridership in the majority of US cities. And it’s worth saying explicitly: the relative unattractiveness of buses in the US in terms of travel time stems from both fast cars and slow buses.

BRT has the benefit of improving both sides of this coin. Prioritizing buses on an existing corridor does mean marginally slowing down cars. Transit signal priority adds delay to private vehicles, and reduced capacity generally means some level of additional delay. Doing European style local buses only improves one side of the coin, but in tons of places this is potentially sufficient. The inner Division section of the FX2 demonstrates this well, and a 15% improvement here is about as good as the corridor could have dreamed of. It’s not like we can go from two regular travel lanes to zero*. The issue there was that this improvement on Division has been treated as if it’s a MAX-level transit line, when it’s still much closer to the preceding bus service than that.

*citation needed

Reserve BRT Funding For Actual Rapid Transit

I get that it’s tempting to pursue federal grants. There’s no better money to spend than someone else’s money after all. But if projects like the FX2 – which essentially amount to the minimum viable European local bus route – are what we fund as BRT, then what exactly is our longer term outlook for constructing actual BRT? I reckon they aren’t good.

I think it’s no accident that the truly rapid transit style bus projects that have been built were almost all planned decades ago. The Eugene EmX, the LA Metro Orange/G Line, and the various Pittsburgh busways all predate the 2007/8 recession. As these projects saw success for less investment than a typical light rail line, the FTA and other transit agencies took notice – but the resulting projects usually steer closer to TriMet’s FX than Eugene’s EmX. It’s easier for politicians to use pseudo BRT as a solution that benefits everyone. No need to scare all the tax paying motorists away with taking away lanes, you can just not do that and the FTA will give you $75M all the same.

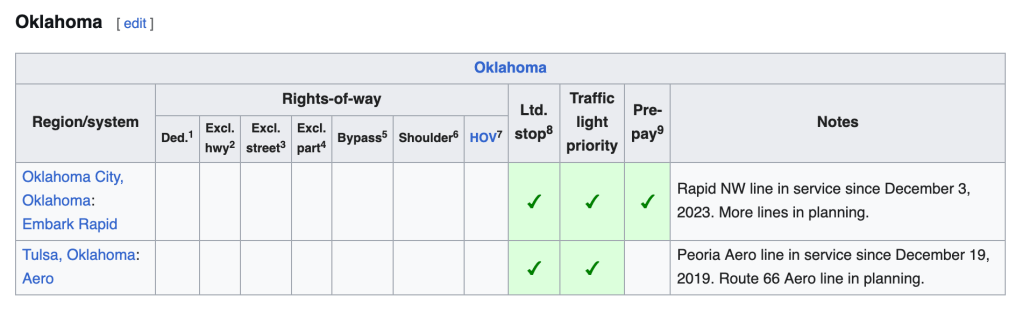

All of these pseudo BRT projects – the Vine in Vancouver, the FX in Portland, the Aero in Tulsa, the Pace Pulsa in suburban Chicago, the Dixie Rapid in Louisville (you get the idea) – are surely improvements to what came before, and were worth building, but calling them “rapid transit” and comparing them to rail transit is absurd. We should fund bus improvements, but we shouldn’t pretend we’re building BRT when it’s obvious to anyone who looks closely that it isn’t.

It should be obvious to anyone who rides transit or follows the news that we can’t always count on the federal government to fund projects. And even when they do, we certainly can’t count on them to fund good projects. I feel strongly that advocates, planners, and bus riders need to speak clearly about the costs, benefits, and drawbacks of the plans that we collectively make. Labeling everything better than the typical dysfunctional US bus as “BRT” serves no one other than the feeble politicians who imagine the highest and best use of sparse roadway space as adding more car travel lanes.

If there is any transit mode native to the US, it’s the bus. While I yearn for the halcyon days of yore when streetcars still plied the quiet streets of [insert your hometown here], the reality is that buses can do everything streetcars can for less money right now. Getting bus service right matters a lot, and I think that having local public agencies take the lead on that is a necessity. Upgrading every heavily trafficked trunk bus route in the US to minimum viable European standards is no mean feat, but it’s something that could be done locally.

Parting Thoughts

If we consider our local system, TriMet has about 6,000 stops in the network, 700 of which have shelters. The upper end of cost for basic bus shelters in 2018 was $10,000. Closing half of stops and adding a shelter to each remaining stop would cost $23M. I guess a lot has changed in the procurement world since, so maybe double it to $50M. But then if we reduce the scope of improvements down to just current or future frequent service routes (~50% of the network), we head back down to the $25M range. Add in ticket machines, and we’re looking at an additional $25M to $50M (at $20k to $50k a piece [2022]). Planning and engagement around what specific bus stops may close, and other odds and ends brings us to let’s say $100M.

A project of this size probably needs external funding. Would Metro voters bite on a bond measure? It’s hard to say, but TriMet could (in theory) sell the public on the benefits in two ways. First, there would be absolute increases in route speed. The 2 had a 17% reduction in travel time on a typical weekday in the wake of the Division Transit Project. How much of this had to do with stop spacing is debatable, but it’s intuitive that it matters. A typical “stop penalty” for a bus is 25s, so going from 40 stops to 20 (as was the case on Division) should save about 9 minutes if every stop were always used. This is rarely the case, so maybe in reality it’s about 5 or 6 minutes saved – which would be a bit over half of the 17% reduction. I think a 10% travel time reduction is a fair guesstimate – enough to begin further research and planning anyways.

And secondly, a 10% reduction in travel time for all frequent service routes would amount to some $12M in yearly savings on labor alone, since a faster bus route requires fewer operators to maintain a consistent level of service. Spending $100M to save $12M per year is a no brainer, since it would pay for itself in like 8 years.

A key dynamic in these FX projects is just how incredibly expensive they are for what we end up getting. Sure, $175M would be dirt cheap for rapid transit, but of course we aren’t getting that. At this rate of $175M per line, it would cost some $3B to upgrade the frequent service network. That’s almost certainly too much to spend in the eyes of the public. But if we can get 50% of the benefits for 3% of the cost, that’s a good investment. If we want Portland to be a sustainable place that centers public transportation, this is where we should start.

It should be clear by now, less than a month into a new horrible era of federal government malfeasance, that we need to have a local focus to our problems. Funding for transit is sparse, and seems to get sparser every year. Making a bold step into the future is still possible, it just requires some leadership. Do we have that? It remains to be seen.

Thanks for reading – til next time.

Leave a comment