If you’re an American, the idea of a small homestead farm on a 40 to 120 acre lot is probably what you imagine when you think of farmland. In Oregon, when the state land use law system was set up, this idea of rural land was codified, both in the form of the urban growth boundary and in the form of 80 acre minimum lot sizes for dwellings in rural areas. The tacit assumption in these regulations is that an urban area (with high population densities) is incongruous with a rural one (with homestead farms).

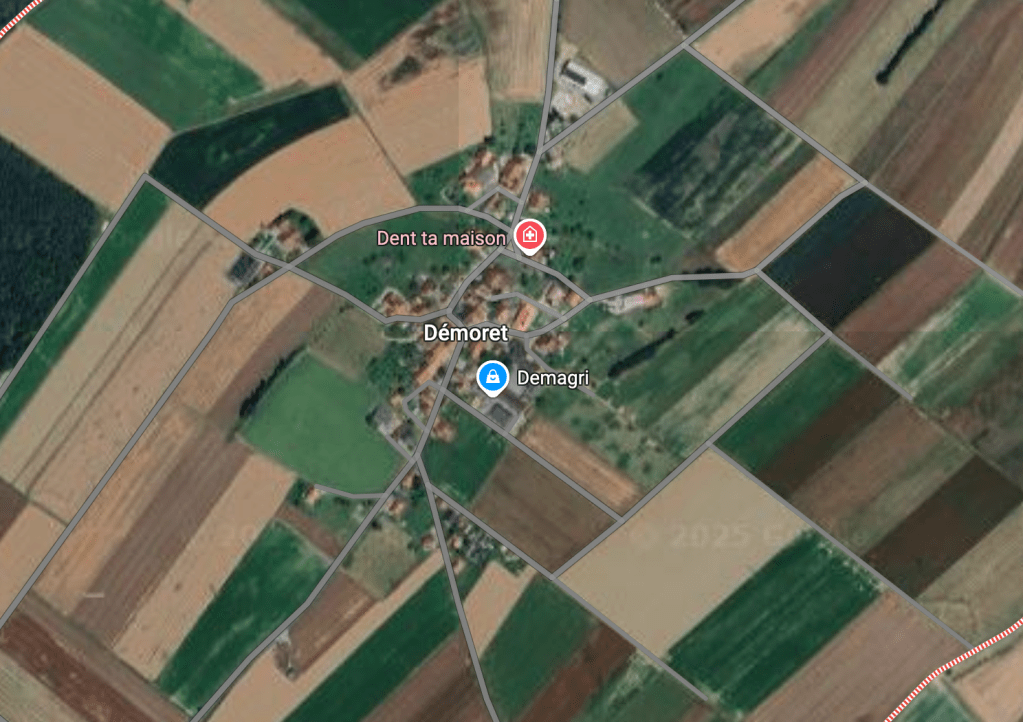

In other parts of the world, where settlement of rural land was less regimented and where human settlement patterns long predate the modern age, the differentiation between urban and rural cannot be done neatly on population density lines. Let’s consider the Swiss municipality of Démoret, about 20 miles north of Lausanne. It’s an unambiguously rural place with a population of just 141. If you just check the Wikipedia, you’ll see that it has a US level of rural population density – about 85 people per square mile (~30 acres per four people). But a glance at the satellite will show that almost all of the homes are clustered into a small village.

Now I know what you’re thinking: “Swiss villages existing isn’t exactly groundbreaking”. And that’s true. But about half of the employed residents of this village work in the primary sector (i.e. agriculture or other direct resource extraction work). The nearby farms largely do not have dwellings on site, so we can assume that farms are worked by villagers who have a short commute to the field from their picturesque little village. When you compare this to towns of comparable sizes in the US, like Halsey, Oregon you’ll find a rounding error of people working directly in agriculture (the primary sector). Small town Americana is typified by warehousing, manufacturing, transportation, and other rural services more than by direct farm employment.

Of course, our sociocultural conceptualization of rural land plays a large role in this, which is reflected in our state’s land use code. There are a lot of interesting ramifications of this, but as ever, the one that’s most interesting to me is public transportation.

The Post Bus

In Switzerland, the Post Bus carries a whopping 175 million passengers per year. Of course, it’s Switzerland, so the nation-wide integration of all public transportation providers makes using transit genuinely attractive. But still, the decidedly rural canton of Graubünden has car ownership rates (588 per 1,000) lower than every US city other than New York (#2, Newark is at 597 per 1,000). The fact that 14.5% of commuters in Graubünden (population density: 23 people/square mile) use public transit to get to work, a rate greater than Cook County, IL (home of Chicago, population density: 3,200 people/square mile), is legitimately mind blowing.

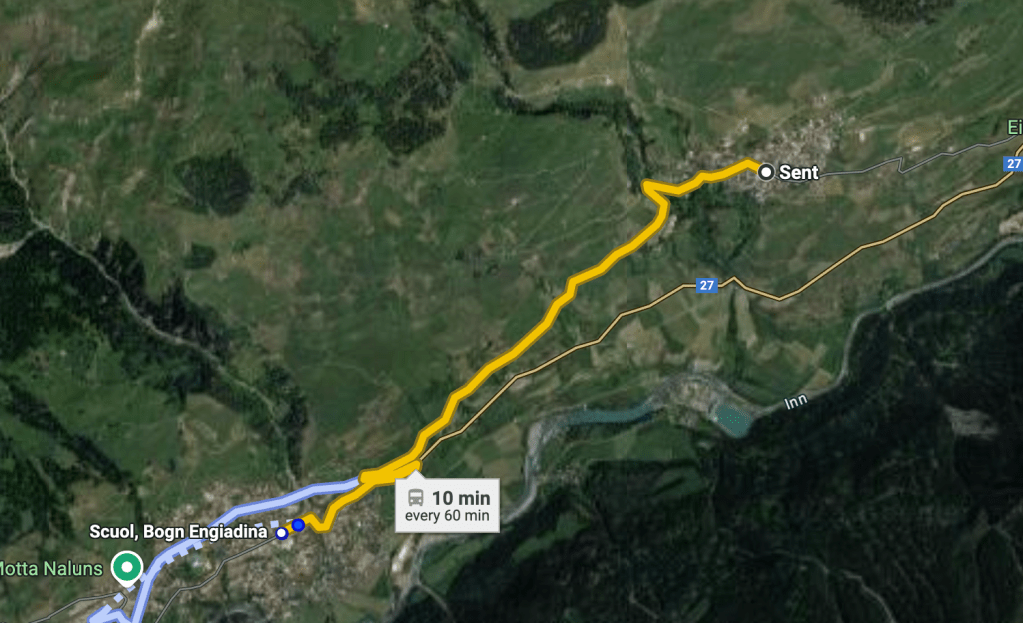

Sure, Graubünden’s population density is reduced significantly by the presence of the Alps, but I could have used Jura (575 cars per 1,000 people), Solothurn (581 cars per 1,000 people), or Vaud (522 cars per 1,000 people) as example rural cantons – none of which are significantly Alpine. The fact is that rural Swiss public transportation is extensive and well-ridden – to an extent that is pretty jaw dropping. In 2023, only seven urbanized areas in the US had higher ridership than the Post Bus (New York, LA, Chicago, DC, San Francisco, Boston, and Philly). Yes, the Post Bus serves the entirety of Switzerland (population 9 million), but most of routes (and therefore ridership) comes from things like an hourly bus between Sent and Scuol in Graubünden.

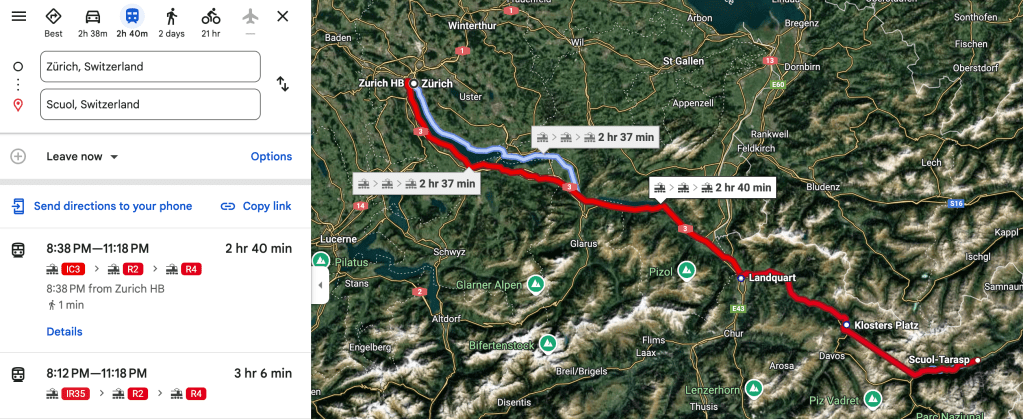

Obviously, this route works in large part because of a truly outstanding rail network. You can get a train from Zurich to just about any other part of Switzerland with a train station for a time that’s analogous to driving.

The extent which rural population density allows for the Post Bus to thrive is not usually discussed (at least in English speaking sources). But it stands to reason that this benefits the provider to a great degree. If everyone lives in a few discrete, dense villages it’s easy to get a bus within a stones throw of their home. If they live on 40 to 80 acre homesteads, this quickly becomes impractical. The fact that about the same number of people ride a rural bus provider in a year in Switzerland as they do in the entirety of Houston, Dallas, and Phoenix combined is not explained on “great intercity train service” alone.

There’s an extent to which Swiss land use (and culture) is driven by topography. Narrow Alpine valleys create natural transportation corridors, removing a dimension of travel and making access to a bus stop or train station less of an ordeal. But even in the parts of Switzerland where topography plays less of a role, you’ll almost always find small clusters of people in villages rather than spread out in the way things are in the US.

Cultural Values and Getting Around

The spread out nature of rural life in the US is at least partly a reflection of our cultural values. Rugged individualism, the Jeffersonian yeoman, and Puritanical ideas about the relationship between land, labor, and ownership play a role here – as do a slew of other things I’m sure. You don’t have to browse Zillow listings in rural places to find the keywords “space”, “seclusion”, and “privacy”. Especially for the country estate type of house, “getting away from it all” is a primary draw. Much of the cultural draw of suburbia exists within this framework as well. A typical suburban pitch is “the best of both worlds” – having a spacious home and yard to yourself, while still being able to access the trappings of modern life.

Even though most US cities came of age before the automobile, this cultural undercurrent has always been a force in American life. The historical need to balance the practicalities of getting around with the cultural desire for independence meant that earlier iterations of public transportation were almost unbelievably large in scope. The US has abandoned more rail lines than any other country has built (as measured by track-mileage), which of course has something to do with the sheer size of the country, but also has something to do with the need for a whole lot of transportation infrastructure to support the more dispersed population.

Urbanists talk in great detail about the need for zoning reform to allow for the population densities to support public transit, and this is tinged with a weak rejection of some parts of the cultural values lined out (while reinforcing others). The walkable city is proposed as the antidote to the isolation of the car-dependent suburb (or exurb). And on these lines, I clearly agree. But I think the narrow focus on zoning, and the urban focus of reforms limits us. It is not a hard and fast truth that rural folks need to be separated by the vast expanses of their farms (or former farms in many exurban cases), it’s an expression of a cultural value.

But any way you slice it, this traditional American rural lifeway can hardly said to be thriving. The rural population in the US is falling in absolute terms, and in free fall in relative terms. With the industrialization of agricultural processes, the need for the Jeffersonian yeoman has rapidly declined (at least economically). Lacking the economic power of yore, and having a generally difficult physical built environment to navigate (typified by long travel distances and few direct neighbors), it’s not surprising to see this. Contrast this with Switzerland, where Post Bus ridership is at an all time high and rural populations are increasing, and you hardly need to have a PhD to draw conclusions.

I won’t argue against the historical justification for the Jeffersonian yeoman, though suffice to say I’m not a big fan. If we need urban land reform to bring us to a more sustainable future, surely we need rural land reform as well.

The Elephant in the Room

And the great owners, who must lose their land in an upheaval, the great owners with access to history, with eyes to read history and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away.

The Grapes of Wrath

While it’s easy to sit in my comfy chair in a cozy apartment in Portland, Oregon and wax about rural land reform, to do it without addressing “the big C” would be difficult. The social issues downstream of the Jeffersonian yeoman are clear, and the Swiss village makes for a neat example, but it is unlikely that we can graft it neatly onto our existing rural landscape. And the cultural aspect of the rural crisis in America is ultimately overrated. The real issues are economic.

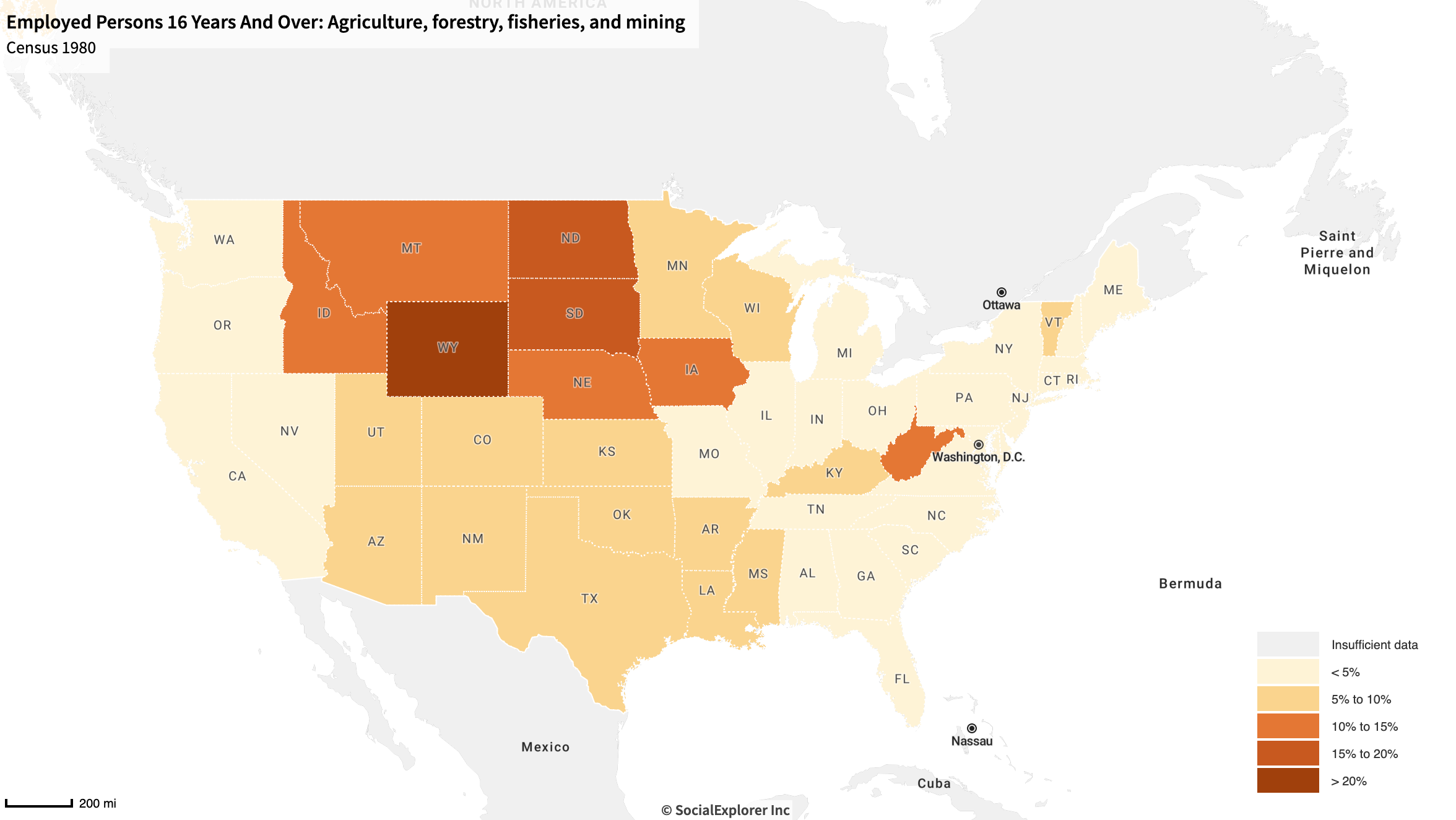

As automation and further industrialization has transformed the rural economy, job losses have been the norm. Even in Wyoming, a state which has seen huge booms in coal, oil, and gas since the 70s and 80s has seen a 25% reduction in jobs in the primary sector. Technological advances mean less labor is required for resource extraction, which means less money flows into rural economies. The benefactors are the corporations, shareholders, and secondary/tertiary workers – who ironically largely live in urban areas. While much has been made about corporate farm ownership and the like, and some trends are worrying, it seems to me that lessening labor requirements are a likelier culprit of rural population declines. Of course, this doesn’t mean that farming is in some stable state – cash-poor farmers relying on credit for new equipment (tractors, etc.) and even seeds (thanks to “breakthroughs” in the GMO world by Monsanto et al.) is generally reflective of a race to the bottom.

As the economic fabric of rural life has declined, there has not been a social fabric to fall back on. Without the need for as many families to own and work farms, the economic incentive is for fewer farmers and correspondingly fewer future farmers. Landlordism is on the rise – with more than half of all cropland in the US being rented – and it doesn’t take a tin foil hate to conclude that socially isolated, small-scale producers have the most to loose in a consolidating future. To the extent that one blames the profit motive and capitalism for this is a personal question, but I have a hard time not seeing a link.

Putting It All Together

The issues of social and economic decline can never fully be separated from each other. European countries tend to do a better job of preserving rural life patterns, but it’s not just about having a more socially cohesive village life. They also do things like the “protected designation of origin” for many agricultural products, which essentially gives local producers a monopoly on key products inherent to the place they operate in. Hence, Parmesan (or Parmigiano Reggiano if you prefer) can only be produced in the Italian provinces of Parma and Reggio Emilia.

To the extent that this kind of agricultural policy has preserved local agricultural jobs is debatable, but it feels like the right direction. Equally important to the story is the role of transportation policy. The Swiss village of your imagination probably has a train station, and certainly has a bus stop with more than a pittance of service. But this sort of investment is made far more difficult in the US, where rural land is literally defined as being low population density. 1,000 people per square mile is used by the Census Bureau as a threshold for urban/rural, an approach which would classify most Swiss villages as urban.*

*a note here: a typical small Swiss municipality (village) includes the adjacent farmland and thus lowers the population density. The US Census Bureau takes a very granular approach to urbanized area – at the household level – so I think it would classify a small village (like Nods in the Canton of Jura) as urban, surrounded by non-urban, even though half of workers in Nods are in the primary (farming/forestry) sector and thus presumably have a close tie to the adjacent farmland as workers/owner-operators.

Public transit works best when a simple, direct route can connect a lot of people. I’ve written before about how the loss of passenger service on the vast majority of rail lines in the US is inextricably linked to the decline of the vaunted American small town, and I stand by that. But simply restoring service levels on every main, branch, and spur line would likely not be enough to move the needle as far as we need. Without some kind of rural land reform towards a village model, actually reaching rural folks via transit will be predicated on car access.

I won’t pretend to have authority on if anyone living in rural American wants this, nor will I insist that it’s a solution to all of the economic and social ills which plague us. But if we can combine a coherent (and well-funded) passenger rail policy with the need for rural land reform intended to revitalize our flailing small towns and rural locales, it will stand a much greater chance of garnering widespread support. So much of our political moment revolves around the urban/rural divide, and if we actually want to bridge it we need to consider what that may look like. I think public transportation is a good place to start, but as ever, its viability is linked to land reform.

Thanks for reading. ‘Til next time.

Leave a comment