From the 1860s to 1904, the Oregon & California Railroad (O&C) defrauded the public for billions. A land-grant era railroad, the O&C received millions of acres from the government in exchange for building a railroad connecting Oregon with California. In 1904, the Oregonian broke the story – the O&C (by then part of the Southern Pacific) committed systematic fraud by way of perusing saloons in Portland to find people to fraudulently apply for the land grants as settlers. The railroad then scooped up all of the land to package them to timber companies – who were not eligible for the land.

I find this bit of Oregon history to be fascinating. Of course, The Octopus of Frank Norris1 engaging in massive fraud at the expense of the public is no surprise. But what’s interesting about this particular case is how the knock on effects of the fraud are still politically relevant in Oregon. In the years that followed the 1904 exposé, something like 100 people were indited for their connections to the fraud, including Senator John Mitchell (one of just five US Senators to be convicted of a crime while in office2). The Federal Government spent decades trying to get the fraudulently disbursed land back, culminating with the Chamberlain-Ferris Act (1916) and the O&C Act (1937). The first act “revested” the land (gave it back to the government), but aimed to give the land back to settlers. This didn’t work for the same reasons the O&C committed fraud: the land was only valuable if you could log it en masse, and a single family wouldn’t really stand a chance.

The 1937 O&C Act recognized this, and gave the respective counties (the 17 counties in Western Oregon – Clatsop + Klamath4) 50% to 75% of the revenue from timber sales on the revested lands. It’s important to note that the intention of this policy was to reimburse counties for the lost tax revenue caused when the federal government took control of the land – but the result is that the O&C counties were given a huge financial incentive to over-harvest timber on these lands. And the counties took advantage of this, with Curry County (one of the more dependent counties on O&C payments) leveraging their federal payments as a means to lower tax burdens – levying a meager 60¢ per $1,000 of assessed value in 2012, just 21% of the state’s average at the time5.

It’s this context – counties which have a clear financial incentive to log as much as possible – which underpinned both the Timber Wars and associated Northwest Forest Plan of the 1990s. While it’s standard Oregon politics to construe owl-loving liberal Portlanders as stymieing hard-working, timber-reliant rural folks, the reality is that federal policy inadvertently played a large role in creating this situation. The O&C timber boom created an unsustainable situation – despite a directive for sustainable harvesting practices. People grew accustomed to the boom times being normal, and the spotted owl became a scapegoat for a collapse that was probably inevitable. The sustainable practices were always “in name only” – total yields were increased from 500 million board-feet in the 1930s to well over 1 billion by the 1960s. These days, total yields are in the 200 million board-feet range6 (a result of diminished supply and more stringent regulations).

Beyond the drama of county insolvencies, a legacy of forest protection direct action, and railroad fraud understanding the ways in which history builds on itself is important to me. When rural communities in Oregon make calls back to the golden days of the logging industry, it’s important to realize how and why these golden days came about. This rhetoric, in the hands of the typically conservative power brokers of rural Oregon inevitably leads to tax cuts in seek of prosperity. This is never the answer, especially in an economic environment where automation, corporate consolidation, and lowering job prospects are the norm7.

And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that the normative way of dealing with environmental devastation in the US is not a practical solution. The usual choice – expanding a wilderness area – means excluding the possibility for sustainably living with the land. Of course, having critical habitat plus some wilderness style areas is no crime – I am a known National Parks enjoyer – but we need be able to have a productive relationship with land. And I don’t say this because we need to extract shareholder value from the land, rather our collective lives are enriched by a cohesive and positive relationship with the land. Or maybe I’ve been watching too many Studio Ghibli films lately.

Visiting the O&C Revested Lands

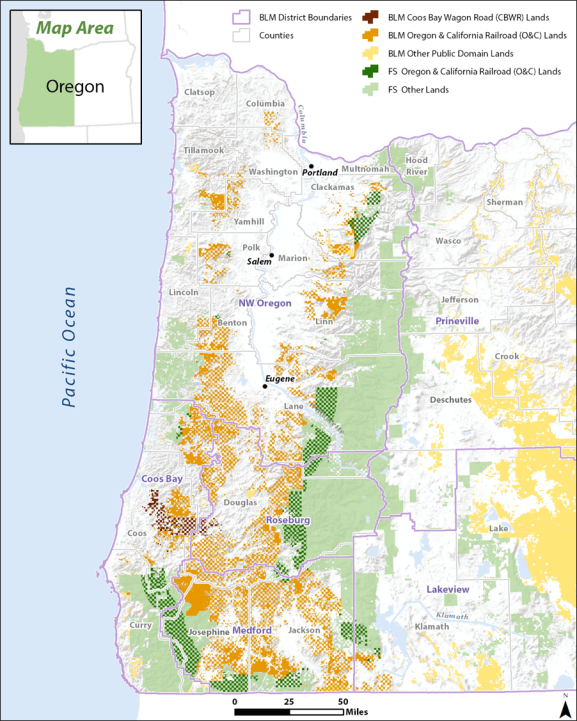

While glancing over the maps of the O&C lands, I couldn’t help but notice that some of the land is within a shout of Portland. So I figured, why not ride my bike out there to check them out? It turns out that I already have!

Way back in 2022, I rode the famous Netsucca River Road on my way to the coast. En route, I recall seeing a handful of Bureau of Land Management (BLM) managed campsites. At the time, I didn’t think much of it. But it turns out that this was O&C land – as all BLM land in western Oregon is. Interestingly, the Netsucca River seemingly hasn’t been as extensively logged as other O&C lands. Perhaps this has something to do with the scenic reputation of the corridor, or maybe it’s just a random chance, but the ride is truly wonderful.

And what do you know, Oxbow Regional Park – a site of another overnight trip of mine from 2021 – is also on O&C land. Metro leases some of the land that Oxbow lies on from the BLM. It’s another beautiful part of Oregon, but also one that doesn’t fit the historical profile of O&C lands. Being directly on the Sandy, less than 5 miles from a historic interurban line (the Mount Hood Railway and Power Company line to Dodge Park8) doesn’t exactly feel like the kind of place where a settler-oriented land grant would have been implausible, but fraud was the first language of the Southern Pacific so it’s not exactly shocking.

Still, I’m not content to just vaguely recall trips from a few years back, wonderful as that trip may have been. But the coast is a long way to go and the weather is not looking inspiring for the next few weeks. So I rode my bike out to the closest O&C revested land to my apartment – a tract just off of Skyline at the corner of Johnson and Beck. There wasn’t much to write home about. A power line running through and some land seemingly used for logging. Was it worth a visit? Of course, I’ll do anything for the bit and the ride was great.

Oxbow and the Netsucca River are unusual for O&C lands in the sense that they are both places that people regularly visit. For the most part, the land is still inaccessible and rugged. But the inaccessibility of today’s O&C land is different than the inaccessibility which started this whole debacle. These days, most of the places that 1800s era pioneers considered remote might as well be a Portland suburb – with no place in the lower 48 being more than 20-odd miles from a road9.

But for much of the land around the O&C Revested lands, it’s still difficult to access. Private companies like Weyerhauser charge up to $500 for access permits10 – despite the proliferation of roads making it perfectly feasible (by 19th century standards) for anyone to get there. But the patchwork of land ownership and timber harvesting orientation of the land makes this access needlessly difficult and cumbersome. Rather than being physically impossible to reach, most of these places are now impossible to reach to protect the valuable timber crop of multinational timber companies.

What Does It All Mean?

Despite its flaws and bad outcomes, the O&C tale shows us a time when the government acted to preserve a public interest over a corporate one. The widespread fraud and abuse that the railroads acted with at the turn of the 20th century is legendary, but the government response tends not to be. Before the functional collapse of the railroads at the hands of the Interstate Highway, the regulatory system set up in response to scandals like the O&C was fairly effective.

Public outrage over these corporate abuses was intense enough to create multiple competing third-party movements – the turn of the century Socialist Party of Eugene Debs and the Progressive Party of Bob La Follette. The results of this broader reform movement, culminating in the New Deal, was genuine change for the better, even if the third parties stalled out. The dismantling of the public sector in the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement and Vietnam war protests should be understood as a regressive step backwards from the New Deal.

It seems clear to me on reflection that the techno-optimism that colored my youth (2000 to 2015) was at least partly a result of this dynamic. As the role of the public sector was continually eroded, future monopolies like Google and Apple established themselves as places where the private sector would innovate and improve life for us all. But as these companies have entrenched themselves as ubiquitous, the optimistic tinge has washed away11 replaced by more cynical corporate dominance. The result is that our regulatory systems have been gutted, trust in public institutions is low (as they are continually underfunded), and everything is geared towards algorithmically maximal exploitation.

Things weren’t so different at the turn of 20th century. Sure, the technology wasn’t as insufferably advanced, but the post-Civil War era was certainly marked by dogmatic adherence to laissez faire principles and a general distrust of public institutions. I can’t speak as to if similar conditions will create the sort of political conditions that led to the O&C Act of 1937, but part of the value of looking into the history of this for me is taking some modicum of inspiration. Even if the results of the O&C Act were deeply flawed, this was mostly to do with the perverse incentive it gave the respective counties as it related to logging on those lands.

The broader victory – of partially breaking the power of a corporation for public benefits – is worth relishing in. And the fact that some of my favorite places in Oregon (Oxbow, Netsucca) happen to be land taken back by the government this way is the cherry on top. Maybe there’s no one lesson, but I’m happy that public access has been maintained to a great deal of places as a result. Even if logging policy remains a sore spot, it seems easier to change logging policy on public lands than private lands, and I’ll take the free ride down the Netsucca River Road over the $500 ride through Weyerhauser lands.

Thanks for reading – let me know if you’ve visited any of these places, or if you have strong feelings about 19th century rail policy.

Footnotes

- A classic book, inspired by the Southern Pacific’s outrageous behavior in California ↩︎

- I think SW Mitchell Street in Portland is named after him, but I can’t find proof. ↩︎

- See footnote #6 for source (yes, I did the footnotes out of order) ↩︎

- If you want to read some timber industry propaganda, may I suggest this website? ↩︎

- The Oregonian talked about this, but fails to mention the background relating to why the county gets specific payments in the first place ↩︎

- For further reading on these figures and others, this congressional brief has good stuff ↩︎

- The Oregonian also talked about this, with a circa 2000 tax cut playing a huge role here. ↩︎

- Formerly home to a seemingly lovely campsite as well, but no longer ↩︎

- This article is so chock-filled with hubris I may just have to write another piece about it, but it quotes 21.7 miles from the nearest road in Yellowstone ↩︎

- There’s something that really bothers me about this stuff, but you can look at their website if you want ↩︎

- I think this is best summed up in the opening sentence of this Wiki: “Don’t be evil is Google’s former motto” ↩︎

Leave a comment