I’ve been reading a lot of economics recently. If you think it’s because was in an economics class in my last term, I regret to inform you that this has nothing to do with the readings for that class (which I actually did do most of, but this isn’t about those). This has led to something of a personal crisis at times. I mean isn’t economics just a bogus subject people study to reinforce right-wing ideas about the free market and competition?

It turns out the answer to that question is no, or at least not entirely. See, there’s entire sub-fields within economics dedicated to leftist ideas, you just can’t be afraid of the word “Marxist”. Even if I’ve got a copy of Capital, it’s hard for me to self-identify as a Marxist when I barely got 50 pages in last time I tried. But I am earnestly interested in the way the economy works in practice, and have become increasingly so as I’ve studied urban planning. So many of the problems planners face boil down to economics, and the approach to solve those problems inherit the basic worldview of the people attempting to do that.

So let’s start with the low-hanging fruit: the housing crisis, the housing market, and what the field as arrived at for solutions.

Roots of the Crisis

While pundits in the New York Times boldly claim that the crisis is “unprecedented”1, our current crisis is hardly new. One only has to consider the depression era “Hoovervilles” before you realize that the more things change, the more they stay the same. If you think the lack of adequate housing in the Great Depression is too hyperbolic a comparison for our current situation, the Dickensian slums of the Second Industrial Revolution will do as well.

While there are surely tomes of reports detailing the solutions to these historic housing crises, the idea I come back to is typically American: they were solved via massive improvements in transportation. The slums of Five Points and the Lower East Side were massively improved by the expansion of the New York Subway – providing all but the poorest a 5¢ ride out into the suburbs of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Harlem, and the South Bronx (an idea referred to as the “one-way ticket” – reducing the need for workers to crowd near major employers and walk to work2).

But as subway construction slowed at the dawn of the Robert Moses era, and as automobility began gripping the nation, these one-time reliefs on urban housing via transit-oriented suburban development began to fade. Thus, a new housing crisis fomented, just as a massive economic crisis arrived. While the auto-oriented suburb of the post War era required a huge amount of public policy innovation and intervention – from the fixed-term, government backed mortgage to the Interstate Highway System – it also represents another one-time solution to the crisis. Once you develop auto-oriented suburbs and codify them as the only use, you can’t just create the same type of suburb again when prices inevitably rise. The further away a suburb is from a job core, the lower value it is, since land value is an essentially location-based trait.

Thus, while our current crisis is obviously linked to the 2008 financial crisis and the American idea of housing as a commodity, it’s unique from it’s historic counterparts in that there is no transportation revolution coming around the bend3. Maybe that’s what they said in 1880 and 1930 too though. Ultimately, American housing and land use issues have historically been “solved”4 via cheap land. What happens when we run out?

No, We Can’t Just Sprawl

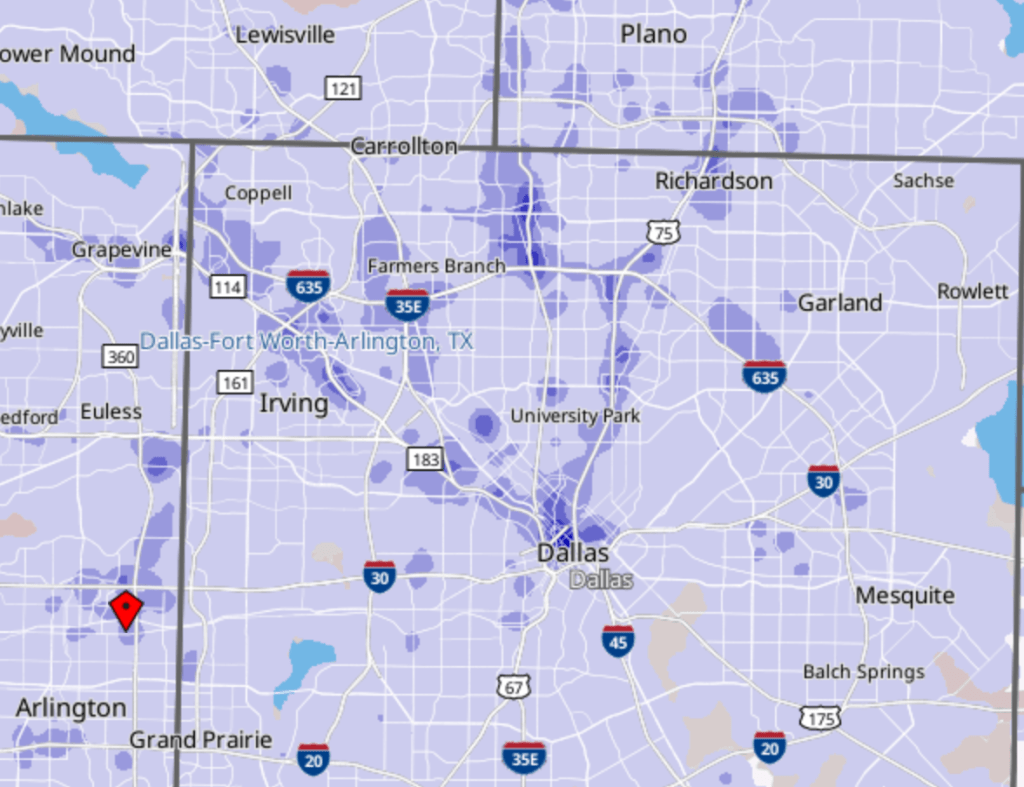

If you’re the type of person to read breathy pundit pieces, like this one from the NYT, you may think that we can just sprawl our way to a solution with no issue. Of course, this idea is environmentally catastrophic, probably financially ruinous, and generally distasteful (the perfect trifecta for a NYT pundit). It also won’t work. Let’s consider Dallas-Fort Worth, like the Times did.

In the map above, we can see the geographic distribution of jobs in and around Dallas. A major cluster in downtown Dallas, as well a big node at the interchange between the Dallas North Tollway and I-635. Princeton, among the fastest growing places in the country, at the fringe of urban development in Dallas, is a 2 hour drive from downtown in the AM peak5. And it’s not much better to the major cluster at the DNT and I-635 (up to an hour and 40 minutes).

While it’s true that these job clusters correlate to historically logical transportation nodes – with downtown Dallas being the site of a major rail and highway interchanges and the DNT/I-635 obviously being a freeway interchange – they also acquire a life of their own as that benefit wanes. The tendency for Dallas to sprawl north has shifted jobs that way, but that’s a much slower process than building suburbs, and one that has serious issues for south Dallas residents.

Absent faster transportation, suburban sprawl is eventually a fools errand. The NYT thinks we can get around this, by assuming that Princeton, Texas is to Dallas as Oakland is to San Fransico. Sure, cities have historically developed in uneven and expansionary ways, but this isn’t some fact of life, it’s a result of the nexus of human choice and transportation availability. And for what it’s worth, Princeton, Texas – a two hour drive in traffic to Dallas – has more in common with Tracy or Livermore than Oakland, something anyone with a functioning brain could tell you. Only a New York Times piece could say something like this with a straight face:

“Over decades, places like Plano and Frisco will come to look and feel more like central Dallas.”

As someone who has incidentally spent time in both Frisco and Dallas, this couldn’t be more of an exaggeration. Frisco’s main commercial center is a suburban shopping mall called “Stonebriar Mall at the Bridges” (with “Bridges” in reference to the freeway interchanges nearby). Dallas is a major legacy city that resembles an actual urban area despite being in Texas. If Plano and Frisco become the central nodes of the Dallas-Fort Worth area, it will be the result of human action and agency, not the inevitable march of some natural law.

Whats more while Dallas is affordable in terms of housing, when you consider both housing and transportation as a portion of income, Dallas is hardly a trendsetter. At 35.5% in 2022-23, it’s lower than every MSA in the Western US, but only by a hair: Denver comes in at 36.6%, Seattle at 36.7%. Meanwhile, the legacy regions of the Midwest and Northeast all beat Dallas handsomely – Chicago (34.3%), Philadelphia (34.1%), and Boston (33.5) all are examples of places that, while not exactly compact, are not actively sprawling in the way Dallas is.6

Essentially, Dallas sprawling ad infinitum has no real benefit to the general public, and if there is a benefactor, it’s probably just land developers. Yes, people can afford larger homes in the Dallas suburbs than they could in an older suburb of Philadelphia, but you won’t convince me that’s a positive for society.

Better Land Use Policy Is Necessary But Not Sufficient

Lots of the discussion around the housing crisis locally talks about “unlocking” new development potentially via relaxing a host of regulatory requirements. In Portland, this process has yielded some promise – as the Residential Infill Program 1 year report shows7 – but home prices are still generally unaffordable, with a $150k salary required to afford a median priced home8.

The issue with land use policy as a means to boost housing supply is that we are still fully reliant on the private market to have the desire, knowledge, and structure to create said housing. If you haven’t noticed, the entire last 100 years of American housing development has been essentially that of the single family home – with a sprinkling of the condo tower since the 1980s. Developers often lack the ability to develop small-scale apartments and condos, and our legal frameworks often prevent middle housing from being attractive on the development side. With tighter margins on housing for the lower end of the market (as a townhome or quadplex would be), there is just more money to be had in developing large detached homes or high-end condos.

This tendency is evident in the “death of the starter home”.9 As margins are smaller for small homes, an anti-competitive market tends away from them – and as any Georgist will tell you10, land is inherently monopolistic. Evidently, this same idea has driven the car market to create larger models with a plethora of extra features. The anti-competitive nature of the car market, coupled the bastardization of CAFE standards to benefit large, inefficient cars with higher margins for manufacturers means that middle-income consumers get priced out to favor high-income tastes11.

But beyond these issues inherent to the housing market, the biggest problem with using our current land use policy framework to alleviate a crisis is that it takes too long. When activists promise that townhouses, cottage clusters, and n-plexes will assist in reducing the cost of living in Portland, and this fails to make an impact at the bottom of the market, you risk cultivating a reactionary backlash. Thankfully, this hasn’t been a huge issue locally – there is broad support for the middle housing reforms that have occurred best I can tell – but market-oriented reforms can only go so far in actually reducing the effects of the housing crisis.

Commodified housing always seems to be expensive in the long run. Since economic power is ultimately derived from land in some way, there’s a tendency for the rich and powerful to accrue it at the expense of the public. The problem with land use reforms in our existing system is that they focus (by definition) on the use of land rather than on the control of land.

Land Reform is Hard

If you have the misfortune of reading the news, you may have noticed that the current US regime is admitting White Afrikaners as refugees12. This is not even thinly veiled racial politics13, but the stated justification of land expropriation targeting White Afrikaners robbing them of their land without just compensation being enough to call them a refugee is worth exploring as well. In the US, the takings clause of the fifth amendment …

“nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”

… prevents the government from taking land for public use without paying a fair market price for it, and this idea is underpinning the Trump administrations stated justification for targeting this particular group of people for refugee status. Again, we all know why they are doing it (because they are racist clowns) but invoking the sanctity of private property to justify this is interesting – especially if you consider the ways in which the Trump family fortune is linked to urban renewal projects in New York (which were made possible by the government playing a bit fast and loose with “just compensation”), but that’s a whole nother can of worms14.

If you work in urban planning, the takings clause is the primary means by which land use decisions are litigated – interpreted for land use law via the Nollan/Dolan cases15. In short, taking land via eminent domain, or even regulating the use of private land in a way that would render it economically useless, can only be done if there is good reason to do so (“essential nexus” is the legal jargon). This makes doing any kind of large-scale land reform not only prohibitively expensive, as each property owner would have to be justly compensated at or above the fair market value, but also of questionable effectiveness. If the public has to pay the rich landowner a very high price, the re-distributive benefits of doing so are minimized – since we are giving a whole boat load of money to already wealthy people.

Of course, the US famously did not give just compensation to the Native tribes whose land they stole, nor did they give just compensation for the various mid-century urban renewal projects16. If our current legal system posits that just compensation must be paid, the effect in practice is that just compensation must be paid to people who can afford to litigate. Naturally, this makes the only possibility for broad-based land reform to be taking land from the already economically disenfranchised.

Evidently, this kind of legal apparatus is bad on its face. The lack of ability for public bodies to redistribute land in an equitable way ultimately underlies our housing crisis in the sense that it prevents the historically logical option. Especially in pre-industrial societies, it was common for rulers to garner popular support by forgiving debts and redistributing land17, but this practice has continued to the modern age18. Our only hope in the US for any kind of economic redistribution (after all the stolen Native land was disbursed) has been to simply create a different class of oligarchs. Throughout history, as technological change has shifted the balance of economic power, the owners of that new production mode have massively benefited – sometimes at the relative expense of the old power brokers. Railroad robber barons rising to power diminished the economic standing of the large colonial landholders, and tech robber barons rising to power has diminished the economic standing of the great financial institutions (to some extent, anyways)19.

This gives the illusion of a society where people can rise to the top, if only they work hard enough. What is really required to rise to the top of American society is good timing with a transformative technology, and this surely explains part of why Americans are so willing to embrace technological progress as dogma. You too can be a bigger boot and be your own boss if you only get in on the ground floor of my crypto scheme.

In this context, land reform as a means to resolve our housing crisis feels somewhere between “outrageously daunting” and “impossible”. But if we want to live in a just society that is continuously improving, we may not have another choice.

We Still Need to Try

While mainstream economics is sullied by its association with being a post-hoc justification for the rich and powerful to be rich and powerful, there is plenty of evidence showing that our current ossified economic approach causes more harm than it needs to. The concentration of land in the hands of the few leads to economic power concentrated in the hands of the few, and thus income and wealth inequality rise in turn. It’s this rising tide of inequality which crushes the the hopes and dreams of the middle and working classes. Prices go up to cater to the wealthy, and especially for scarce goods like housing, the result is that poor and middle income people get priced out of areas altogether20.

And this issue of gentrification further widens the income and wealth gaps. Poorer people end up on land further from central areas worth less, and the rich displacers benefit from their newly acquired high value land. Now the neoclassical economist would respond by saying the poor person displaced got a fair market value for their land, but it’s usually not that simple. Poorer people have less of an ability to withstand difficult financial times, so may be induced to sell for less than the full long term value. Or they may be renters, forced out as their absentee landlord sells land off to make way for new market rate housing.

In any case, left to its own devices in our current highly unequal economic system, we should expect land to concentrate in the hands of the wealthy at the expense of the poor. We can try to solve this issue by building affordable housing in high demand areas, but the issues inherent to American affordable housing make this quite challenging21. We could attempt to build publicly owned affordable housing, and the fact that this is the more realistic option for alleviating the housing crisis in practice tells you all you need to know.

But all of these issues dance around the fact that allowing wealth (in the form of land) to steadily accumulate in the hands of the richest is bad for our society. And it’s a self-reinforcing trend: as the rich gain more land and wealth they can extract even higher rents, income inequality deepens, thus allowing them to gain even more land and wealth. If we are unable to do any kind of land reform (without further accelerating the transfer of wealth up the ladder), then we eventually end up back in the bad old days of the latifundia.

What to Do?

This all isn’t to say that we can’t alleviate our current housing crisis without large-scale, unconstitutional land reform, just that if we fail to consider the long term ramifications of economic inequality on things like the housing market, we may find ourselves carrying a knife to a gun fight. Good land use policy matters as a means of slowing the rise of future feudal landlord overlords, but we cannot solely rely on our current system to do so.

If we rely solely on market forces to regulate the supply of land, things will never work out as intended. Unlike other goods, land has a fixed supply. While we can increase supply of housing by increasing urban density, we cannot increase the supply of land. If our land use policy fails to address this, and instead treats land as just another thing, we loose to the large landholders who instinctively know that their high-value land is irreplaceable.

There isn’t a silver bullet solution here unfortunately, which is surely part of why YIMBY-oriented groups tend to be making political winds: one size fits all approaches are politically popular (their implicit alignment with powerful developers can’t hurt either, but there’s not an explicit conspiracy). Urban land politics tend to be reduced to three categories: homeowners, renters, and developers, with renters usually getting the short end of the stick no matter what. Finding a way to provide cheap affordable housing to everyone is ultimately what we should aspire to; how this is done seems like a tough nut to crack. But I’ll close with some of my thoughts on solutions – all of which fall short of full land reform, but have the benefit of being legal (mostly anyways):

- Rent to own: create a legal apparatus by which some part of a renters monthly rent goes towards the purchase of the unit. Allow renters to receive this money (with interest) if they choose to move out, and do some creative accounting to make sure current landlords aren’t totally screwed by it. While this may cause rents to rise, since the rental market is at least nominally competitive, it would probably end up being a combination of landlord profit reduction and higher rents.

- Expanding affordable housing into publicly built homes: rather than limiting our affordable housing schema to subsidized rentals, the government could build housing directly, then sell it at a loss. I realize there are lots of problems with this idea, but I feel like we could make it work

- Co-ops: Housing co-ops are a bit of an unknown in most of the US, and are probably most strongly associated with “alternative lifestyles”, but limited equity co-ops are super cool and offer a much lower-cost ownership option22. Any co-op structure provides affordability be removing the speculative value of the underlying land – something which is good for the public, but “bad” for someone hoping for an unearned windfall after sitting on land for a generation without improvement.

- Just go buck wild on publicly owned housing: Call this the Vienna solution and just build so many affordable public housing units that they have an appreciable impact on the local rent market. Is it likely to occur? Not really, but I do think we can theoretically afford to do it.

- Increasing tenant protections: While your local neoclassical economics study group shudders at the idea of rent control, since it reduces the incentives for landlords to generously provide housing, reconsidering the legal relationship between landlords and tenants should have the effect of de-financializing land transactions. Policy can be crafted to find some middle ground, but rethinking tenure23 needs to play a role in the future of a more equitable land system. Everything from eviction protection to rent increase limits involves some modest renegotiation of the legal relationship between landlord and tenant, and I think that’s exciting (even if the specifics of any given provision may be of little note).

- Property tax reform: Oregon is a state where the “tax revolt” era produced a massive reduction in property taxes. Given that there are strong economic cases for a robust property taxation system (ranging from land value tax to more typical systems), we should consider this to be both economically inefficient and deeply unfair. I’m more considered with the fairness – so basically any reform will improve things, but a well-structured land taxation system should be designed to reduce the appeal of speculating on land, which in turn has been shown to improve outcomes in urban areas.

- Very high marginal taxes on non-primary homes: While the effect of real estate speculation is downplayed by free market acolytes, land’s inherent traits of being permanent and scarce make it a great vessel for wealth storage. Thus, having policy that attempts to reduce the demand for non-primary dwelling uses should at least help to alleviate the supply constraints many major cities face. In some cities (Vancouver and NYC come to mind) newly built condos are used more as stores of wealth for foreign investors than as actual housing. We shouldn’t sit idly by and allow that to happen, and a high marginal property tax on homes not used for living has the benefit over an outright ban of generating revenue (that could be spent on other affordable housing options).

This has been a sprawling post, but the dynamics of land in urban economics is criminally under-taught and under-studied. I think it’s worth considering in some depth, and would strongly recommend reading Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing if my 3,500+ words about the topic weren’t enough.

Thanks for reading – ’til next time!

Footnotes

- Link to the NYT article ↩︎

- Further reading on this if you’re interested ↩︎

- Incidentally, high-speed rail boosters tend to claim it as a solution to these woes – but we should be wary of the impact. A high speed line connecting Portland to Seattle in 60 minutes is likely to induce land value rises in Portland that would make our housing market look more like Seattle’s (that is, “absolutely outrageous” instead of “insane”) ↩︎

- Just like they solved global warming in Futurama! ↩︎

- I’d rather be dead in Oregon than alive in the north Dallas suburbs to be honest. The commutes look insane. ↩︎

- Per the BLS: full tables here ↩︎

- Link to the report here: it’s worth a read. ↩︎

- Sometimes the news is really not great. On that note, is anyone hiring? ↩︎

- Reluctant link to a realtor site ↩︎

- I’m not much of a Georgist, but I do find some of his stuff to be of interest ↩︎

- Most articles (here, here) I could find on this strongly emphasize the role of regulation and underplay the role the manufacturers in the US have historically played in creating the “mega car” issue. In the pre-1970s oil crisis days, the same car bloat issue occurred almost solely because of “the big three” pushing bloated monstrosities on the public. This book provides a good historical background on this. ↩︎

- Link the AP post if you haven’t read about it yet ↩︎

- I would like to expand more on the racial politics of the US publicly supporting remnant pro-apartheid aspects of South African society but it feels a bit daunting to me. Here is a brief summary of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa – hopefully something I can come back to ↩︎

- Further reading on this topic if you’re interested ↩︎

- There’s also the Koontz and Sheetz cases, but the ramifications of those cases are less sweeping and more technical. Further reading. ↩︎

- For post WWII highway building, there are serious questions as to if residents were paid fair pre-highway plan compensation, or if they paid post-highway plan prices (link). In either case, getting just compensation for property these days usually requires an expensive lawyer and it stands to reason that the tendency for highways to go through the poorest parts of towns meant less potential for litigation as a result. ↩︎

- Look! Even the Financial Times agrees! ↩︎

- Usually in the aftermath of a major war or revolution – Maoist China was built on land reform, as was the modern German state ↩︎

- Important to note that there is of course a lot of interchange, and the “losers” in any of these situations are almost always still extremely well off. ↩︎

- See this book for more details on this dynamic (primarily focused on the UK, but illuminating for the US as well) [Chapter One as a pdf] ↩︎

- Yet another “topic for another time”, but chief among these is the fact that American affordable housing policy requires tenants to be rent burdened ↩︎

- And yes, this article about them is in Eugene (which will never beat the alternative lifestyle allegations) ↩︎

- Tenure is the broad term for any property relationship (renting, owning, leaseholding, limited equity co-op, condo, etc.). This book from footnote 20 also has a lot to say about this. ↩︎

Leave a comment