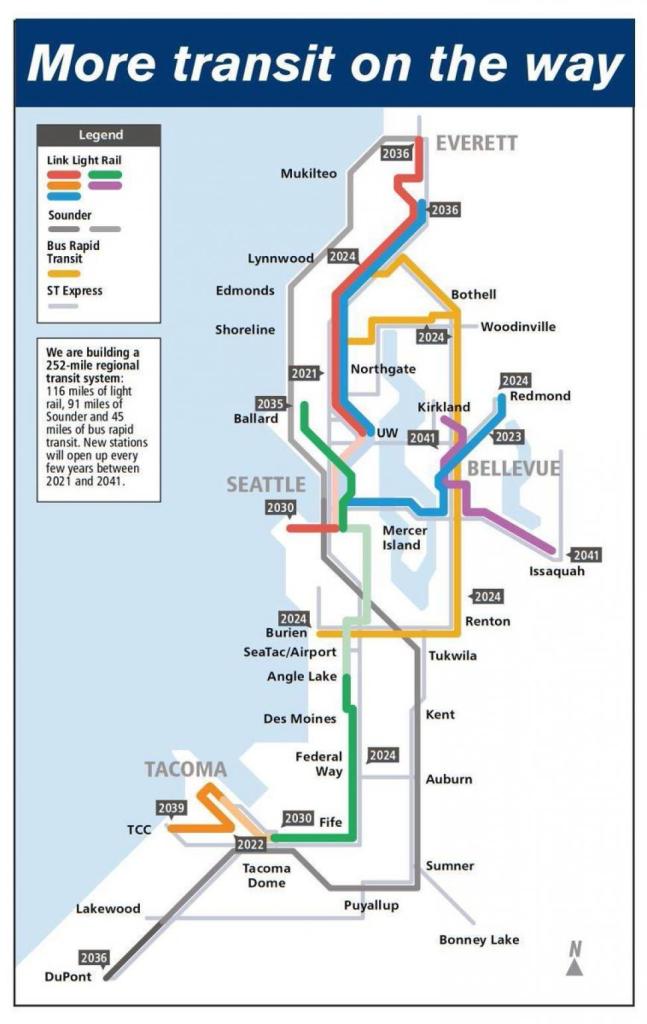

In 2009, Seattle finally joined Portland by opening a light rail line. The Central Link project, consisting of refurbishing the existing downtown bus tunnel and the rest of the line from Sodo to Tukwila, cost some $2.5 billion and forever transformed the transit scene in Seattle’s South End. Well that’s how the story goes anyways.

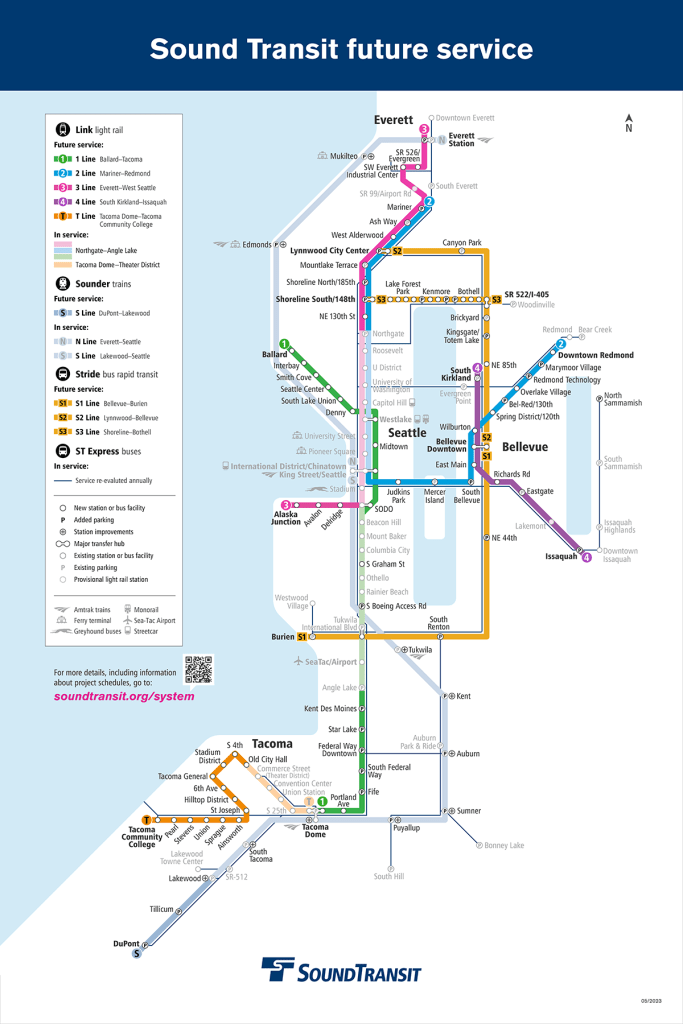

Before I made the move up to Seattle, I caught wind of a decision that didn’t make much sense to me – Sound Transit was forgoing a transfer with the new Ballard Link and Chinatown/International District/King Street Station1. As a regular Seattle visitor, I’d frequently used the current Chinatown/International District station to get from the train station to points north. With a massive expansion underway, I couldn’t really understand why this objectively2 bad choice for the regional transit network was being made.

I didn’t look into it much further, since there were more urgent things to do. But now I’m here and I live in the South End, so it’s a bit more urgent (if you believe that the Ballard Link project will be built by the 2045 timeline it has now).

Chinatown and Construction

In the original Sound Transit 3 ballot measure, Chinatown/International District was envisioned as a transfer point between the Ballard line, the east side line, and the West Seattle/north side lines. As the point where the east side line meets the current 1 Line, it’s a natural transfer point. Adding to this, Chinatown/International District is one of the highest ridership parts of the City of Seattle. Oh, and it’s across the street from the busiest intercity rail station in the Pacific Northwest.

In short: it’s a good place for a major transfer hub. But there are fundamental issues in doing complicated construction projects in the area. The first, is the fact that in the early 20th century, the fashionable thing to do was to knock hills down to fill the wetlands and salt flats making up the Duwamish estuary. The second, is that Chinatown/International District has been subject to a great deal of disinvestment from the City and region over the last hundred years.

While it’s easy to draw a line on a map and make a bubble, it’s less easy to make a construction project happen. Sound Transit identified three locations to actually put a new station: 4th, 5th, and Dearborn-ish3. From a network design perspective, the only really bad one is Dearborn – since it’s nearly a quarter mile from the existing station and even further from any bus routes (sorry to the 554 – you’re being cancelled and you didn’t stop there anyways). But 4th and 5th come with problems of their own – one physical, one cultural.

On 4th, the history of Seattle filling as much of the Duwamish River estuary with the tops of nearby hills is the primary concern. Land fill makes for difficult construction – especially for deep bore tunnels – and 4th is approximately the former shoreline. While this option is possible in the technical sense, it’s significantly more complex than transit advocates like to imagine. It would (apparently) involve rebuilding the existing viaduct and would take 10 to 12 years4.

And on 5th, the history of Chinatown/International District’s disinvestment, neglect, and active malice from local politicians comes to a head when a long construction timeline would leave local businesses out to dry for years. Or that’s the general story – but there’s more to consider as well. After all, Chinatown/International District is the neighborhood in Seattle with the highest rate of transit usage5 and has an existing light rail station. Surely the thousands of people using public transit every day would welcome the increased transit provision implied by a major light rail extension.

Well, Why Don’t They?

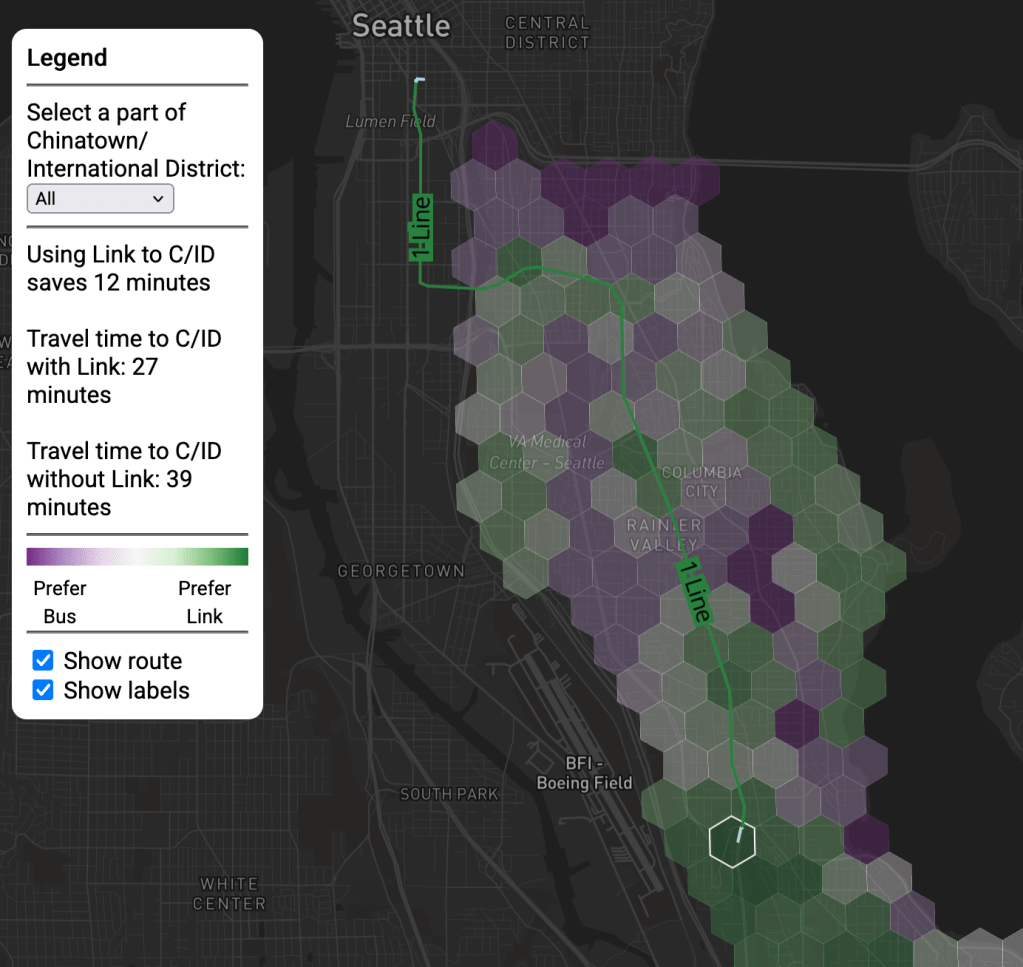

The Census Tracts that encompass Chinatown/International District may have over a 1,000 workers using public transit, but less than a third of those use the existing light rail line to do so6. Compare this to the tracts that encompass Capitol Hill7, where well over half of transit riders use light rail to get to work. Whatever reason for the reason this difference may be, conflating new light rail extensions with better transit for a local community isn’t always strictly accurate. But here’s my two cents: the Central Link project does a generally poor job of giving transit riders a better option than existing bus services, and this is essentially the only segment of the current and soon-to-finish projects8 where that is the case.

Speed may not be the only relevant metric to judge a transit project by, but I think its a useful starting point. And it’s easy to explain why a Capitol Hill – UW commuter may prefer the Link to the Metro Route 49: it’s ten minutes faster. In the South End, there are few trips that are appreciably faster on Link. To illustrate this, here’s an interactive map showing travel times from four parts of Chinatown to the South End of Seattle and unincorporated Skyway. Below are a few example trips that I think illustrate this:

As you can see in the examples, the only places that are in the “always take Link” category are either on top of a station are are in places that lack a direct bus downtown (as Seward Park and the western edge of Beacon Hill). Everywhere else is either strongly favored by the bus, or it will depend on where specifically in Chinatown/International District you are heading.

And while it’s easy to read the news about MLK and the issues it causes with reliability and speed, reality is not that simple. If we look at Beacon Hill (below) – a place where a transfer would involve no at-grade sections – you see that the 36 is close enough in speed to the Link from the Beacon Hill Station that a transfer just isn’t worth it. On the north side of town, this is never the case (below).

| Start | End | Bus time (rte) | Link time |

| Capitol Hill | UW | 17 min (#43) | 4 min |

| Capitol Hill | U District | 16 min (#49) | 6 min |

| U District | Roosevelt | 8 min (#67) | 1 min |

What Does It All Mean?

While the specific acute causes of the anti-second Chinatown backlash relating to feelings of disinvestment and difficult underlying soil conditions are certainly the most clear proximate causes, we should not dismiss the relative lack of utility for the majority of South End residents that the existing Link line provides. To be clear, it’s a good transit line, but in comparison to the segment of Link between Westlake and Roosevelt, it’s not.

How much this matters is up to you. I feel lucky as a new Beacon Hill resident that I’ve got extremely reliable and useful buses to pair with a pretty useful light rail line. And since I’m a weirdo, I even get a bit of extra enjoyment out of riding the #36 as a legacy route that’s still electrified9. But one only needs to sit at Westlake station at rush hour10 and compare the crowds heading north to those heading south and realize that the social base of train riders in North Seattle is a whole lot bigger than it is in South Seattle.

We’ve got some friends who live near the Roosevelt Link station and some who live near Capitol Hill. It’s hard to not be jealous of their almost unbelievably fast train to UW, downtown, and points north. I just waxed about my love for the 36, but it also takes me 20 minutes on the bus to go 2.2 miles home at rush hour. 20 minutes from Westlake gets you across the city line to Shoreline – something like 10 miles away.

And when it comes to building the political coalitions that are required to make a big transportation project, I find that this entire idea to be grossly under-articulated. The fact that Chinatown residents – who are overwhelmingly transit riders – have organized to make the regional light rail system serve them less well may be short sighted to someone who lives in Roosevelt and commutes to UW, but it should be a five alarm fire for transit planners. Or I think it should. When we’re designing a better transit system, the needs of current riders should prioritized over the hypothetical future rider. After all, these are people who already have shown a preference for our current system – won’t they be the ones to use a new one too?

Incidentally, this line of thinking doesn’t pervade most public conversations about mass transit in the US. Most of the discussion around new lines and new systems centers people who don’t ride, but would if it were better11. Of course, we should consider everyone when designing and advocating for better mass transit: it’s a public utility that needs to be for everyone. But still, when I think about who will benefit most from new transit investments I’m not usually thinking about drivers who are afraid of getting on the bus (despite it being pretty good). If we want to get people onto our existing bus systems, it’s not clear to me that the issue is anything other than widespread anti-bus stigma mixed with the overwhelming convenience of driving for most trips12.

And here we’ve arrived at a crucial point: new transit investment is usually framed as solving some problem with the old stuff, with the assumption that people who haven’t been riding will now try it (and like it). In Seattle, the Link has been essentially an unqualified success, just with a qualification that most of the ridership is not coming from the South End, partly because it’s a bit too slow here. While it’s easy to pontificate about why, the obvious explanation is historical circumstance. When Central Link opened, Seattle was coming out of the Great Recession worse for the wear and probably just excited to have anything at all.

But now, this historical circumstance is coming home to roost. 55 minute trips from Federal Way (express bus travel time: 35 minutes) is just the latest example of how Sound Transit’s regional light rail system was always a mixed bag. When it’s designed like a metro (Westlake and points north), it gets crush loads. When it’s designed like a tram (Mount Baker to Rainier Beach), it gets stuck at traffic lights and hit by cars with a decent number of folks on board. But I’ll save the paths that coulda woulda shoulda been taken here for a later date. For now, I’ll close by saying this: ride the bus, trains are cool too, but there is a 100% chance you live in a place where you could ride the bus more often. What’s stopping you?

Thanks for reading, ’til next time.

Footnotes

- This was the video I saw about it. Looking at some of the comments now make me angry enough that I’m glad to have just sort of watched it and thought “huh, seems weird” back then. I just read a comment from someone saying a circumferential rail route from Magnolia to Queen Anne and then somewhere east of I5 would be a good idea. Sigh. ↩︎

- By “objective” I’m referencing the utility for riders. Of course, you can judge a transit system any way you want, but I think that’s the most instructive one. ↩︎

- It’s worth saying that there’s another potential option: run everything through the existing tunnel. I personally think this is the obvious choice, but it hasn’t been formally considered. ↩︎

- Note here: I am skeptical of this, but I have no specific other figures to cite, so we just sort of have to use the official numbers. I’m no engineer, so don’t ask me to guesstimate if it’s possible to build this station for significantly less. ↩︎

- By commute share anyways – at almost 50% (City of Seattle) ↩︎

- Sourced from ACS Table B08006 ↩︎

- Same ACS Table, different geographies ↩︎

- As in the Federal Way Extension and the East Link project ↩︎

- I touched on this in an earlier post ↩︎

- As one does ↩︎

- This isn’t a problem per se, and in many ways is perfectly natural. After all, mass transit is still essentially a rounding error of transportation trips nationally (outside NYC). There are a lot more “potential riders” than “current riders” ↩︎

- A critical note on this: “most trips” is meant in the sense that if you looked at every possible trip, driving would be more convenient for almost all of them. In my experience, people don’t consider every possible trip, but if you have a group of friends whose normative transportation mode is the car, you can bet you’ll find yourself riding your bike to St. John’s while they catch a cab. ↩︎

Leave a comment