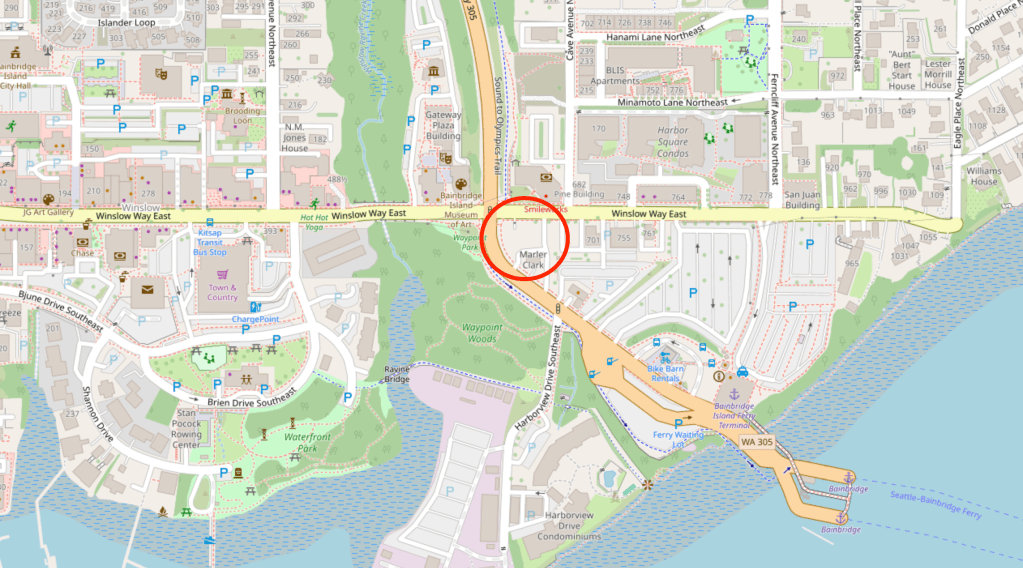

I recently had the misfortune of reading a poorly articulated op-ed in the Seattle Times. It was so bad that I feel the need to respond to it in depth, and the Times limits letters to the editor to 200 words, so that won’t do1. The op-ed in question can be found here, and it’s a response to an opinion column that is worth a read here. In summary, the original opinion column talks about how the responses to Bainbridge Island’s unending saga of a single affordable housing complex at the corner of Winslow Way and WA 305 are steeped in generalized NIMBY attitudes that are often wholly blind to the realities of life for wage workers on Bainbridge.

A key point is that housing on Bainbridge is almost unfathomably unaffordable – with average home prices nearing $1.5 million, and rents approaching $3,000 (if you can even find a unit). Pearl-clutching about how a 90-unit affordable housing complex on a visible and publicly owned parcel “doesn’t fit the character of Bainbridge” is essentially saying that we don’t believe affordable housing fits in our concept of Bainbridge Island.

The response, written by James Forsher, is borderline unreadable. Instead of addressing any of the specific points about the specific parcel, he chooses to engage in whataboutisms concerning development on Bainbridge writ large. This is obvious when you consider his first two points about water and sewer connections with any amount of a critical eye. Let’s start with water.

Part 1: Water

Forsher begins by saying that “Bainbridge Island depends almost entirely on groundwater [and] no comprehensive, recent study has been conducted to determine whether local water tables are rising or declining”, and “homes outside the downtown core rely on private wells”. While concern of the water table is justifiable, and the specifics of Bainbridge’s water situation (as an island reliant on groundwater) matter, this is a bad-faith argument for two reasons.

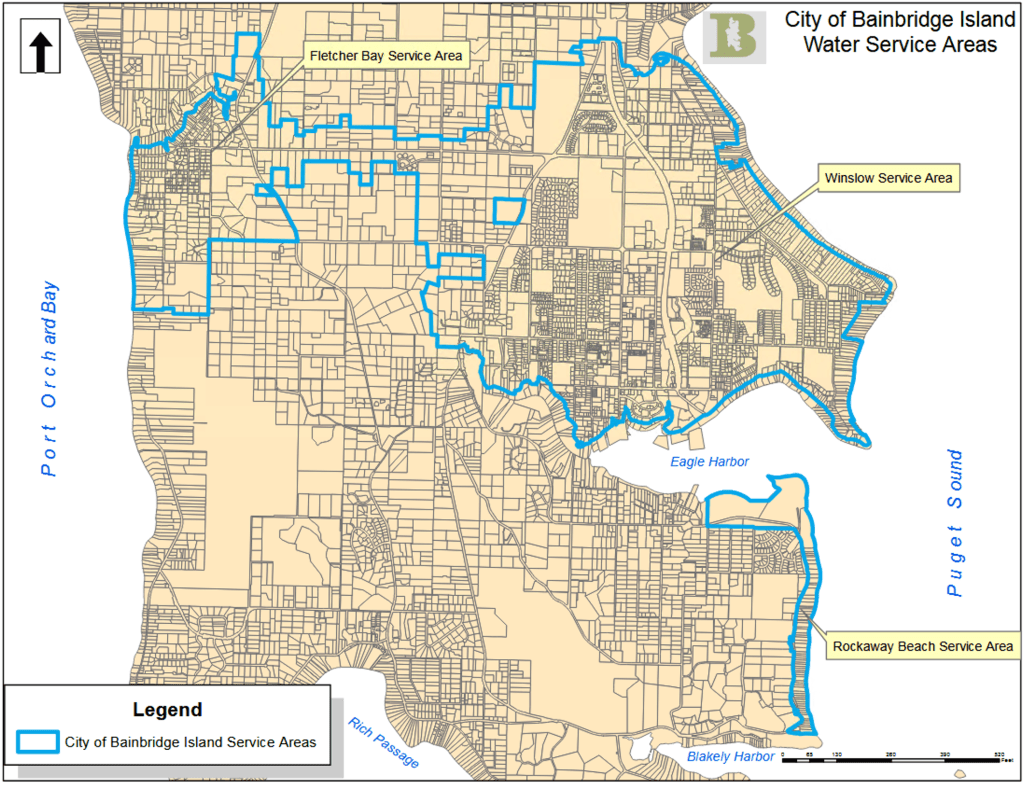

The first is obvious: this housing development is in downtown Bainbridge, and is thus served by the Bainbridge water utility. This doesn’t excuse the development from being party to the generalized water situation on the island, but it does make you wonder why the author would bother talking about how homes outside the downtown core rely on private wells.

The second is more nuanced, and requires a brief look at the current plans for Bainbridge’s water utility. But first, let’s look at some context. According to the city, the water utility provides 200 million gallons of water to 6,000 customers per year2. Based on this study of water usage in multifamily units nationally, we can expect the 90 units in question to use in the neighborhood of 4 million gallons per year, or about 2% of the total water usage on in downtown Bainbridge3. That is potentially concerning, but there’s a large gap between “potentially” and “actually”.

Here it’s worth saying that nationally, per-capita water usage is about 25% lower in multi-family units than single family ones4, and that water rates on Bainbridge Island are low5. Since rates are low, and water usage is correlated to cost, if new development goes in and strains the water system necessitating costly interventions the likely outcome is reducing per-capita water usage. That seems fine to me, even if using prices to do so can be unfair. And from the perspective of usage by density, preventing multi-family development (in favor of existing single family homes) is not really justifiable, as per-capita water usage declines with density6. Of course, in absolute terms a new multi-family development will have a high water usage, but is this the relevant metric? If we are concerned about groundwater management, we should take a more holistic view at how the resource is managed island-wide.

So let’s consult the in-progress Bainbridge Island Groundwater Management Plan7. The draft report8 makes some key recommendations, none of which are “prevent new development”. Instead, they focus on reducing water use through programs, better surface and storm water management, and well monitoring programs. Most of these have more to do with protecting groundwater in the sort of rural lot that Forsher lives on than they do with justifying reducing development capacity in downtown Bainbridge.

And while there are legitimate long-term ground water concerns on Bainbridge Island, it doesn’t seem like the Bainbridge water utility is all that concerned with capacity. They are still allowing for new hookups, and none of the planning documents that I see contain language to suggest that the situation is dire enough to justify something like a development moratorium. Forsher is wrong to imply otherwise.

Part 2: Sewer

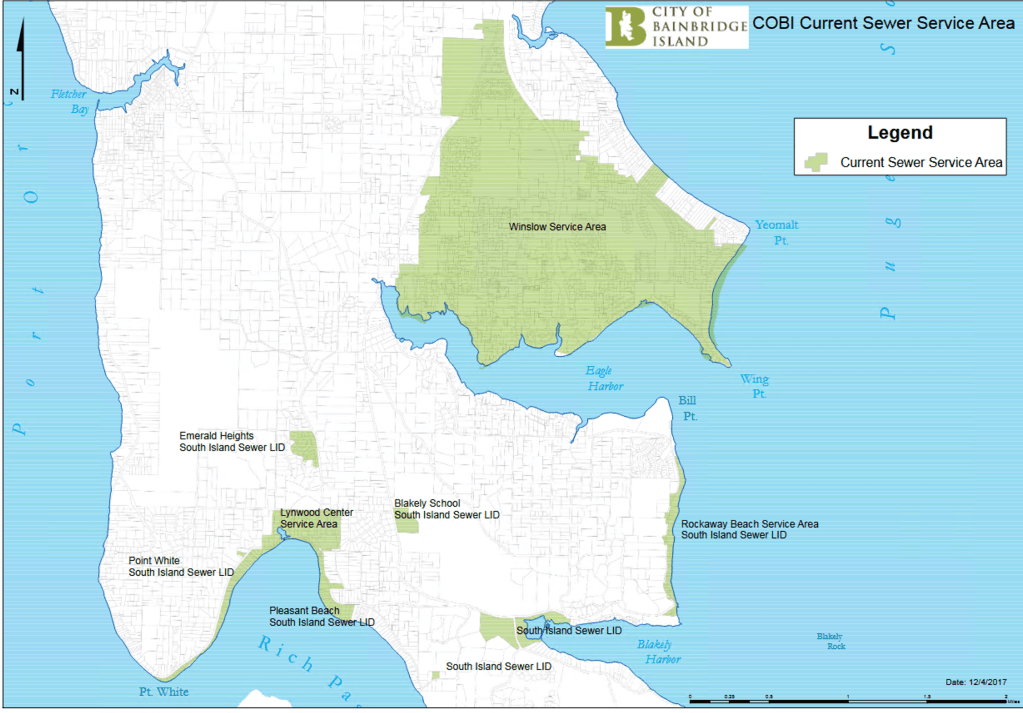

While there are actual constraints that developers and residents of Bainbridge have to navigate with respect to groundwater, the same cannot be said of sewer. At least those who live in the service utility area (which is basically all of Winslow/downtown). True to form, Forsher chooses to ignore the fact that the development in question is in downtown Bainbridge and served by a sewer system with no capacity constraints and relatively low rates. Instead, he says: “[b]ecause most of the island is rural, new housing is constrained by septic system requirements…. [and these] are environmental realities tied to soil and wastewater capacity.”

This is true of where he lives in Bainbridge. But – and this is crucial – it’s not true of where the development is slated to go in. The sewer utility that serves downtown Bainbridge is doing fine, and wastewater treatment is generally more flexible to groundwater concerns than something like drinking water. His points are pure whatboutisms that border on the absurd.

Wait, This Guy has a PhD in Urban Planning?!

As I was reading this, I thought to myself “oh great, another rich retiree on Bainbridge Island who doesn’t know how to read a capital improvement plan and has already decided that they are against something (for anti-urban and anti-working class reasons), but they rightfully view their actual reasons as distasteful (even to themselves) so they have to find a post-hoc justification for an unjustifiable political belief”9. Then I saw the tagline of “James Forsher is a retired university professor with a PhD in urban planning”.

I’m trying not to steer this into a discussion about the merits of the author as a person or scholar, and would instead prefer to focus on their talking points, but it is worth considering the ramifications of that credential being included (by the author). If you read this article – one responding to a journalist with no specific training in urban planning – you may come away with the impression that Forsher knows what he’s talking about, and the original article missed some key details about sewer and water policy. People see a PhD and think that person is an expert.

But urban planning is a large, sprawling, and poorly defined discipline – especially in the academy – and reading that he had a career in media and academia is somewhat telling. Because academics are not often dealing with the specifics of a city’s Groundwater Management Plans; they are dealing with something more theoretical (and thus worthy of “objective” study). Forsher seems to be more of a scholar of film (and its relation to urban spaces)10 than a technical expert in development or event land use planning11.

And on that note, I’m sure he could provide great insights into something like the recent discussions over film space at the Port of Seattle. But if you claim a PhD in urban planning, and you want to discuss utility availability about the development of a particular parcel, you should do more homework. If there are gaps or issues with how the City of Bainbridge Island manages their utility services, then that’s an issue worth discussing12. But just vaguely gesturing to septic and well systems in parts of Bainbridge where no one is building an apartment (on account of the lack of urban sewer and water services) is wrong at best and intellectually dishonest at worst.

The Rest Isn’t Great Either

The sewer and water utility discussion contains the most obvious and least genuine parts of Forsher’s op-ed. But the rest of it isn’t great either. Let’s do a quick point by point breakdown:

- “The term “affordable housing” is often used imprecisely. The real issue is housing affordable to people earning below a specific income threshold.”

- No duh, and that’s why the building being developed is designated as affordable for people earning below a certain income. There are issues with this system – massive, crippling issues – but Forsher doesn’t mention any of them.

- “When I retired in 2012, I purchased a modest three-bedroom home for $275,000. Thirteen years later, prices have increased dramatically, reflecting national trends rather than a single local failure.”

- The issue is more acute in Bainbridge than elsewhere, and a cursory look at any data will show this. Here’s an obvious one, in 2012 the median home price in the US was $199,100. In 2024, that number was $365,400 or 83% higher. On Bainbridge, those numbers were $590,000 and $1,167,100 or 98% higher. Also of note, there are zero homes like Forsher’s (50% of median value, 0.5 acre lot) on the market now which indicates that he either got a great deal or the market has gotten much worse at the lower end (or both).

- “If a nonprofit produces 50 units over two years, the administrative cost alone can exceed $100,000 per unit”

- Wow, I wonder if there is any reason why nonprofit affordable housing developers would have a hard time developing on Bainbridge, and thus would experience high unit costs? Oh, and the developer in question is Seattle-based anyways, so this point is entirely irrelevant as they have staff working on numerous projects at once. This is just a baffling and poorly thought out point.

- “Rising housing costs exclude people long before community attitudes do.”

- Which is why people want to build affordable housing on Bainbridge Island. Home costs keep people out, and preventing affordable housing from being built is part of that. Is that not a community attitude?

And ironically, his main solution (of expanding ADU development potential) is likely to actually be constrained by sewer services. After all, there are relatively fewer single family homes with a yard for an ADU in the areas served by sewer on Bainbridge Island. At some point, you need to acknowledge that ADUs are not a silver bullet. Rental subsidies are almost certainly impractical as well, as there are just so few apartments on Bainbridge that waitlists are likely to be outrageously long. Something like three quarters of workers on Bainbridge who commute would prefer to live on the island. If there isn’t space, there isn’t space.

And it goes without saying that the obligatory mention of low down payments and paternalistic mentoring programs for prospective home buyers is entirely irrelevant. When the issue is high costs, down payment deferrals only benefit a very narrow segment of the buying market who can afford higher monthly costs now but who are short on capital for a down payment13. On a median Bainbridge home with current interest rates, the mortgage is over $7,000 a month with zero down14. That’s well over $1,000 per month more than a 20% down payment would have.

I work a good job, with good benefits. I can’t afford the $200k+ down needed for a home on Bainbridge, but I also cannot afford the monthly payment even with a 20% down payment. You can’t do financial wizardry to solve this problem. The people who work critical jobs on Bainbridge don’t need financial coaching, they need rent they can afford without living paycheck to paycheck.

At Some Point, You Have to Be For Things in Imperfect Places

I’ve already talked a bit about a process where rich folks gaslight themselves into believing that they aren’t part of a reactionary movement that negatively impacts the working class that they still rely on. Much of the backlash around the development in question stems from the idea that “this corner is too important to our civic identity to develop an affordable housing complex on”. Phrased that way, it’s undeniable that the community in question does not recognize affordable housing in the form of apartment buildings as a legitimate part of their community.

If you only ever say “we support affordable housing, but not here – why not another place?”, you have a moral responsibility to specifically identify those places. But one look at the “Save the Corner” site shows exactly the sort of impractical solutions that Forsher espouses. Dispersed ADU-based solutions are unlikely to be affordable, unlikely to be widespread enough, and unlikely to actually happen. There is no reason to think that 90 or so housing units near one of the only functional transit nodes in Kitsap County would cause significant traffic problems. Larger than say, the WSF car ferry being right there. Smaller scale projects on non-publicly owned land are guaranteed to be more expensive, and it seems like this project is already on the precipice of not working.

The reactionaries on Bainbridge say things like “this is a rare, perhaps once-in-a-lifetime chance to ensure that one of our most prominent public sites reflects the values, pride, and long-term vision of Bainbridge Island“. I agree, and they should do so by ensuring that the workers who provide them with the services that they need to live the charmed life they live have an opportunity to live in their community. It would make me less embarrassed to visit.

Thanks for reading, ’til next time.

Footnotes

- Though yes, I have submitted an abbreviated version to them anyways. ↩︎

- You can find this info here. ↩︎

- This is probably an overestimate, since water usage is correlated to precipitation and Bainbridge is relatively moist. ↩︎

- By unit, it’s 50% but since multifamily units tend to have fewer people it’s best to use per capita numbers. See this study. ↩︎

- Sourced from this rate study ↩︎

- Incidentally, if you look at Bainbridge Island’s water service charges you can see a clear (and potentially unfair) biases against multi-family homes (page 13). I am under the impression this is quite common, and it should be understood as a way in which cities conceptualize multi-family homes as a burden they must tolerate (or risk lawsuits) while single family homes are a basic unit of life. ↩︎

- Which you can find here ↩︎

- Download link here ↩︎

- Yes, it was that exact thought with that many words. ↩︎

- His book, Community of Cinema, seems to be the most relevant here (and an interesting topic!). His other book I can find record of is about using archival film to make your own film more engaging. Seems cool, but not really urban planning. ↩︎

- I want to stress that I don’t think this is an issue, just that saying “PhD in urban planning” for an urban planning topic that you know nothing about is a bit pretentious for my tastes. ↩︎

- I wouldn’t rule this out. It’s not uncommon for utility planning to be shortsighted, and the relationships that developers have with the planning apparatus can be unsavory. But claiming those things still requires some actual, tangible proof of wrongdoing. ↩︎

- This can be important, but other solutions to this problem (like raising property taxes!!!!) are preferable for obvious reasons. ↩︎

- Sourced from here ↩︎

Leave a comment