How the City of Portland killed a neighborhood.

Historical Context

Long before the stadiums and urban renewal areas of the twentieth century, Lower Albina was home to a vibrant community of integrated, working class people. After Albina and East Portland’s consolidation into Portland in 1891, the Lower Albina area – roughly the area between Grand Ave, Oregon Ave, the Willamette and Fremont Ave – became a typical working class neighborhood; with close proximity to the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company yard (now Union Pacific’s Albina yard) being the primary draw.

And until World War II, Lower Albina retained this character of a working class population living close in to a heavily industrial and commercial area. The first changes came around 1950 when the Oregon Department of Transportation completed a re-route to Highway 99W from it’s original designation over the Broadway Bridge to the then-new Harbor Drive, Steel Bridge and a re-aligned Interstate Ave. This required the bulldozing some of the homes and apartments closest to the river, but had much lower impacts relative to the later projects in the area.

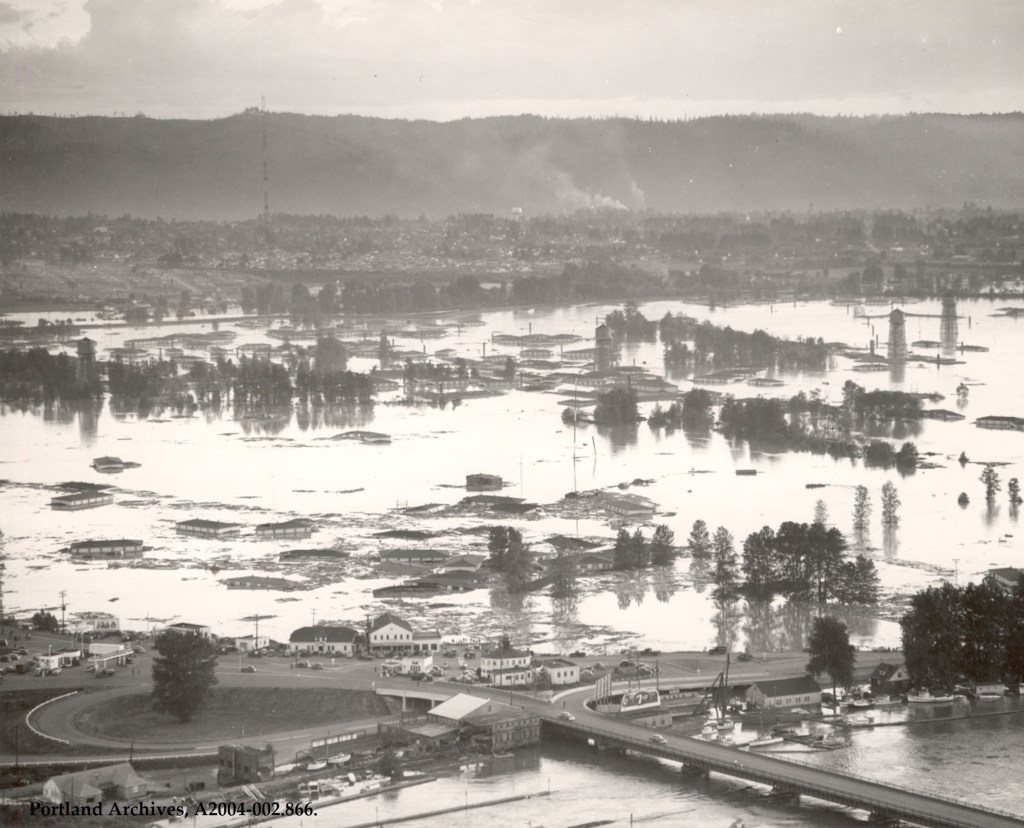

Like most of Portland, Albina as was predominately white until World War II – although Lower Albina had more diversity since it was common for Black men to work as porters or laborers on the railroad. During the war, Portland became the center of shipbuilding on the Pacific coast, which drew ten of thousands of new workers to the area. Housing was scarce and discrimination endemic to Oregon at the time, so most of the Black (and many White) workers moved their families to Vanport – a purpose built settlement for shipyard workers. At its peak during the war, Vanport was home to about 40,000 people (the second largest city in Oregon at the time), with 40% of them being Black – or about 16,000 (which considering that Portland had a pre-war Black population of about 1,800 is very significant). In the spring of 1948, a berm for a railroad broke due to flood waters on the Columbia and the entire city was inundated. Better writers and historians than me have covered the Vanport Flood, so I’ll spare the details here.

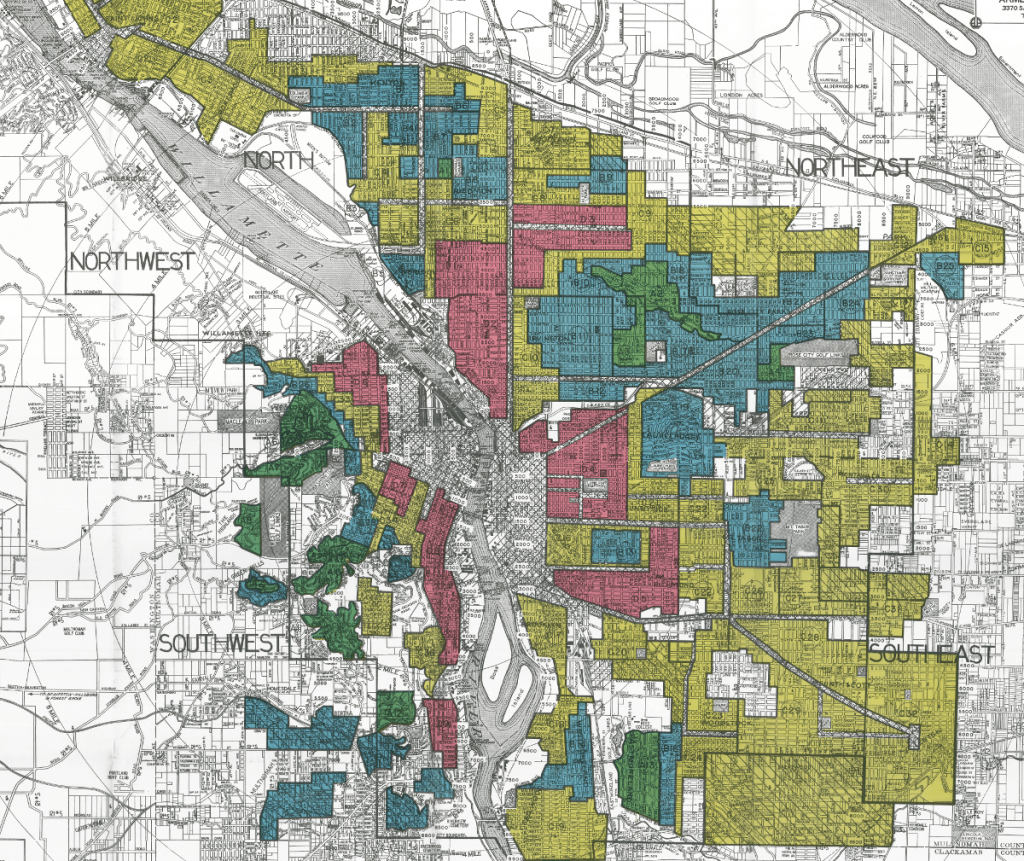

An intense refugee crises unfolded in the days and weeks after the flood, but most of the Black people who had previously lived in Vanport were sequestered into whatever neighborhoods the Housing Authority of Portland, FHA, and various neighborhoods associations would allow. Given Portland’s reputation as a hotbed for white supremacy (Oregon’s statewide Black Exclusion was only repealed 22 years prior to the 1948 flood), and the FHA’s policy of purposeful racial segregation it is no surprise that most of the Black refugees ended up in Lower Albina.

It is hard to overstate how vicious of a practice redlining was. Despite being unconstitutional (even at the time – 1917 Supreme Court Decision Buchanan v. Warley), the US Federal Government enforced racial segregation via FHA policy. I would highly recommend reading both The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein and Sundown Towns by James Loewen for more detailed analysis of redlining in the post-war era, and racism with regards to segregated living areas more generally. All of this to say, most Black refugees ended up in a vibrant, diverse urban community – which in the late 40s and 50s was an affront to the American Dream.

Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum

With rapid suburbanization and the automobile having finished its conquering of American consciousness, city planners in Portland (and nationwide) could begin realizing their dreams of remaking the city in its image. Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum was built with the dreams of wooing a shiny professional sports team to town, and ended up demolishing hundreds of the oldest homes and businesses in East Portland. And while the path to get from “Stadium Proposal” to “bulldoze diverse integrated working class neighborhood” sounds pretty standard nowadays, there are a few twists and turns that make this even more infuriating.

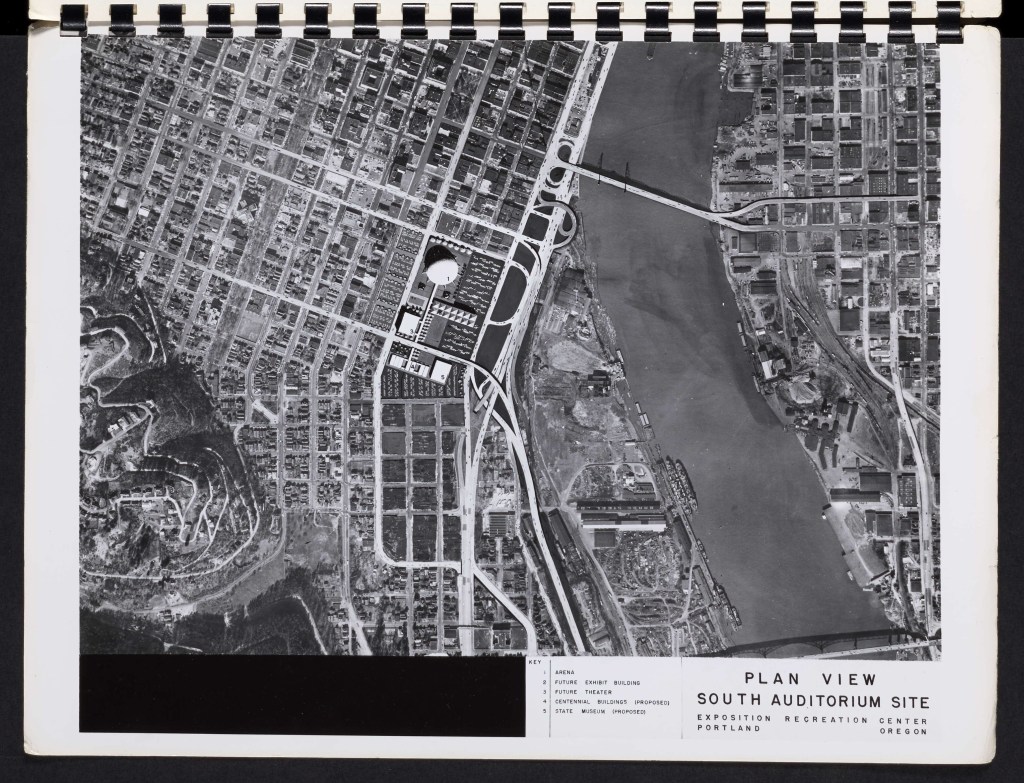

A 1954 $8 million ballot initiative to build an “Exposition-Recreation Center” passed easily for a sports center and park – at a site in Vanport. The site selection apparently wasn’t final though, given that there were multiple other ballot measures after 1954 regarding the Exposition-Recreation Center. The biggest drawbacks for the Vanport site according to a 1954 City Club Bulletin were flood risk and distance from the city center. Given the recent catastrophic flood, the first concern is not exactly surprising – and given the City Club’s clientele (old, rich and white) neither is the second.

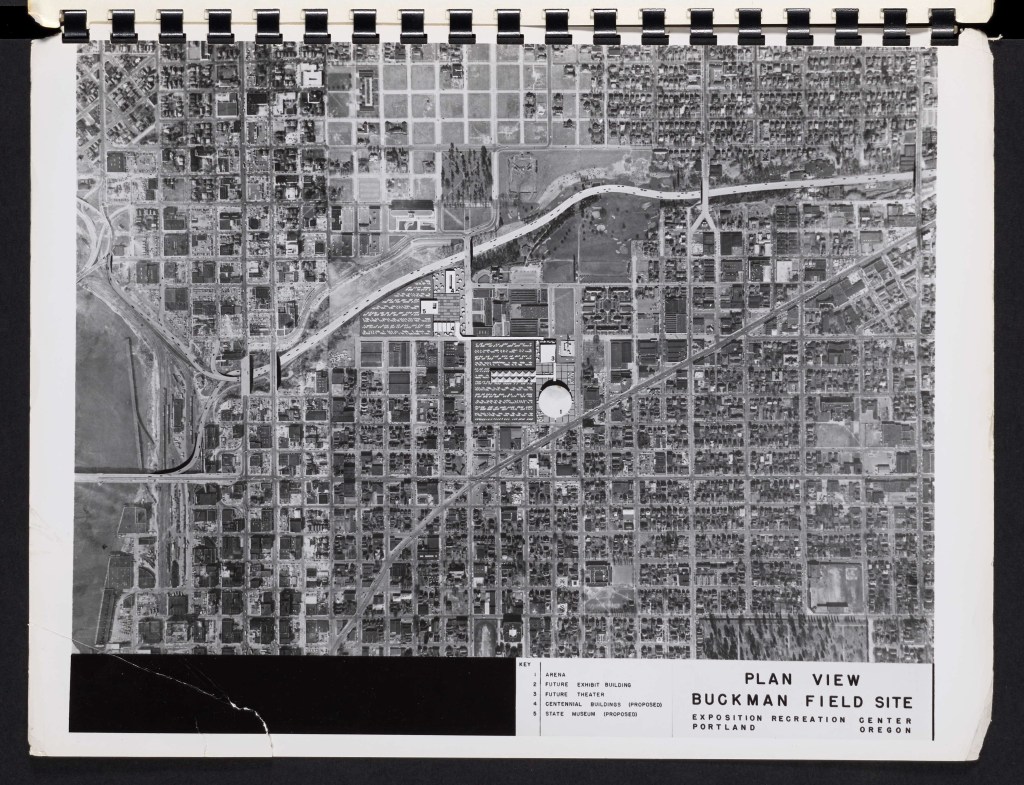

By early 1956, the leading locations for the “Exposition-Recreation Center” that would become Memorial Coliseum were Delta Park/Vanport, South Auditorium, Lower Albina (between the Broadway and Steel Bridges) and Buckman Field (annoyingly not noted on the stadium sites image, but referenced in a 1956 report). A second ballot measure passed in 1956 by less than 500 votes limiting the proposed stadium sites to the east side of the river (thus eliminating the South Auditorium option). The South Auditorium was bulldozed anyways, but primarily for office high rises and the like instead. Buckman Field still exists, and the central Eastside neighborhoods largely escaped urban renewal intact.

In 1958, the 5th (and final) vote was taken to move the site of the “Exposition-Recreation” Center to Delta Park. Despite the fact that, as far as I can tell, there was never any actual vote to move the site from Delta Park/Vanport in the first place (the 1956 vote is worded on just an “Eastside restriction” and I’d say Delta Park is firmly east of the river). A Portland City Club Bulletin concerning this ballot measure recommended a “no” vote, primarily because a fair amount of money had already been spent by the city on the Lower Albina site. I have not been able to find exactly why – but presumably the city planners acted somewhat outside the purview of what was literally allowed by the specific ballot measures (or I am misunderstanding what the meaning of the 1956 vote was).

So after all the hemming and hawing about location, city planners decided to bulldoze the community which took in refugees from Vanport, and that had become the nexus of Black community in Portland – without actual voter approval to boot. Bulldozing the post-Vanport center of Black community, instead of building the Coliseum at the Vanport site shows an impressive lack of care on the part of the city.

But even saying “lack of care” is giving the city too much credit. This excerpt from the 1956 report on potential locations for the Coliseum site mentions explicitly that because the region has fewer owner occupied units (Black families were routinely denied mortgages), experienced a higher degree of overcrowding (Black families were routinely run out of other neighborhoods), and had lower than average income and education relative to the rest of the city – it was a good candidate for “renewal”. Which is to say, the city figured it was better to bulldoze the poorer, more diverse, less financially able than to build the Coliseum in a place where the people they were displacing had already been forced out of (and where no one actually lived anymore).

Interstate Highways

The next “improvement” project to hit Lower Albina in the middle of the 20th century was the Interstate Highway. Starting with I-5 in the late 50’s, the Oregon Department of Transportation bulldozed approximately 90 acres out of 650 acres in Lower Albina for the various freeway projects and their associated infrastructure. The entire Minnesota Freeway project demolished ~330 homes, with approximately a quarter of those coming from Lower Albina. As noted by the good people at City Observatory here, ODOT acquired homes for about $50 each, and did not attempt to build any homes to replace the ones lost.

All too familiar reasons were used to justify the route of I-5 through North Portland. Highway Engineers preferred to follow the path of least political resistance – which meant bulldozing the poorest neighborhoods. Portland is typically noted for it’s “highway revolts” and the cancelling of the Mount Hood Freeway (along with I-505 on the West side). But I-5 was the first* freeway to come to Portland and citizen resistance was relatively small (the Banfield Freeway – now I-84 – was the first freeway built in Portland, but avoided most of the issues of I-5 by following the rail corridor through Sullivan’s Gulch).

While the freeway physically severed Lower Albina in two, the constant noise and traffic served to further depress the situation in general. It is important to remember that the freeways through North Portland still serve both roles – the noise and pollution is physically harmful and generally stressful. All of this has disproportionately affected the lower income, primarily minority residents who have typically been forced (either by the building of, or lack of other opportunity) to live in the marginal areas near freeways. Put simply, a freeway running through a residential area is not acceptable.

In a future post, I will dissect the current “Rose Quarter” “Improvement” Project (and yes, I’d say I disagree with the nomenclature on everything other than “project” here) with it’s promises of congestion relief and building equity for Black Portlanders.

Other “Renewal” Projects

I won’t go into too much detail here, but Lower Albina was also subject to various lower profile urban renewal projects – most notably the Emmanuel Hospital Expansion. The hospital acquired adjacent property through the Portland Development Commissions urban renewal program, and used familiarly shady dealings to demolish the commercial heart of Lower Albina – the intersection of Russel and North Williams.

The Portland Public Schools main office also stands today in Lower Albina near the river – on what was the last vestige of the old residential heart of the area after the construction of the Coliseum. I am not sure if this was done explicitly under the guise of “urban renewal” or not however

Other development patterns reflect the automobile era still, and are distasteful for pedestrians – but I am not certain about the history of urban renewal outside the projects already mentioned.

Lower Albina Today

Because of all this, Lower Albina is one of the least walkable places in Portland. The freeway noise is incessant, the parking lots are massive, and there’s not a whole lot of care for pedestrian accommodations. As much as I do genuinely enjoy exploring the built urban environment, even I have my limits.

It’s this kind of environment that makes it really difficult to change behaviors and get people out of their cars. The Moda Center can have all the transit access in the world, but if crosswalks are forgotten, signs are never updated, and cars are still given absolute priority it will always be a steep road to reducing car trips to the area. And this general theme is something Portland (and the country as a whole) struggle mightily with – if the pedestrian accommodations suck, people will drive. Alternate modes almost always require some amount of walking, and a stressful postgame walk to a train station on dilapidated sidewalks is a big barrier to adoption. A great instagram account (@pdx_bad_drivers) recently shared an experience of theirs, noting that post-event traffic by the Moda Center is typically way worse than post-event traffic at Providence Park (despite the nominally better transit service at the Moda). Providence Park is certainly no transit Shangri-La, but it sure helps that it feels safer (and quieter) to walk around.

Outside the Moda Center area, I-5 and I-405 really make things miserable as well. There are a total of four East/West crossings of I-5 in Lower Albina, two of which the very busy Broadway/Weidler couplet, and two (Russell and Graham) that are uncomfortable under crossings of the massively overbuilt 5/405 interchange. This lack of actual east/west crossings severely limits mobility in the area outside a car – and further serves to divide what’s left of the residential parts of Lower Albina from the “amenities” like the Moda Center and Coliseum.

North of Russell, the area has been heavily gentrified – which I won’t touch on much since I feel it is out of scope here, but would highly recommend reading Bleeding Albina and/or The Portland Black Panthers if you’re interested in a thorough history of Albina in the post WWII era. However, this is also where most of the urban renewal horrors of the mid-twentieth century stop. Due to luck or changing political tides, the residential areas here were spared the bulldozer of the older areas directly south. But the bulk of damage had already been done – the commercial and cultural centers shifted north, towards Alberta Street and the death of Lower Albina as a place that exists at all went relatively unnoticed. In 1973, when Portland moved to formalize neighborhoods, Lower Albina was left out – split amongst Eliot, Boise and Lloyd – either owing to a lack of remaining housing or along school district lines.

The story of Lower Albina isn’t wholly unique. Even within Portland, other neighborhoods faced similar total erasure due to urban renewal – like South Portland (which has had the indignity of being reborn in a totally different urban renewal area) while other parts of Albina suffered equally, if not more, under ghetto conditions imposed by local (and federal) policy. But Lower Albina suffered perhaps the most – and the city is worse off for demolishing it.

References

Portland Ballot Results in the 1950’s: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/auditor/article/4979

City Club Memo 1954: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=oscdl_cityclub

City Club Memo 1958: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1179&context=oscdl_cityclub

Noise in cities: https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.8141291

Sites for the Exposition-Recreation Center: https://multcolib.bibliocommons.com/v2/record/S152C1017061

Leave a reply to The I5 Rose Quarter Project is a Sham – City Hikes Cancel reply