If you know one thing about me these days, it’s that I love a good bus ride. I love the convenience of not driving, but most of all I love seeing the people in my community going about their day to day lives. My local transit agency, TriMet ostensibly agrees here; they have a plan for the future which includes 30% more bus service! But I want to take a deeper look into who TriMet is, what they stand for, and what it means for the bus-loving pedestrians of the Greater Portland Region.

Beginnings

TriMet, like most municipal transit agencies, was founded in the aftermath of the freeway building spree of the 50s and 60s as formerly private bus (and earlier streetcar/interurban services) continued to decline in profitability. TriMet was founded after the near-bankruptcy of Rose City Transit in 1968, and has been with us ever since. But the watershed year for transit in Portland I want to touch on before continuing with TriMet is 1958.

In 1958, the final passenger run on both extant branches of the Portland Traction Company’s interurban lines – the Springwater and Oregon City lines – abruptly ended. In addition, with the completion of new ramps on and off both the Hawthorne and Morrison street bridges, all streetcar service within the city was permanently ended by 1958. And Rose City Transit ceased all electric trolley bus operations in 1958, dismantling key parts of the overhead wire system before city council could act to stop it.

I want to linger on that last point, because it is a continuing point of frustration for me. At the time, Portland (and the Pacific Northwest as a whole) enjoyed easily the least expensive electric rates in the entire country – yet Rose City Transit removed them. In large part, this was to skirt around the Public Utility Commission who had authority to regulate both streetcars and electric trolley buses, but not gas buses. More on the consequences of this later.

So by 1968, TriMet was left to pick up the pieces of a once excellent electric transit system and try to make the best of it. To their credit, ridership stabilized and recovered after the tumultuous Rose City Transit days – but I am skeptical how much of this can really be attributed to TriMet doing things well (as opposed to just being actively awful like Rose City Transit was). But that’s where I will leave the history – it’s all very interesting, but also very long.

TriMet Today

These days, TriMet has decidedly less cool bus livery and still no trolley buses. They do have five* light rail lines (or two, with a multitude of branches), operate three* (or two, does the loop really count as two??) streetcar lines, run a weird commuter rail line, and about 84 diesel bus lines. However, despite the good stuff TriMet remains a very car-centric transit system – both in operations and philosophy. Let’s unpack that.

You’ll Go Downtown And You’ll Like It

As it currently stands, 42% of all TriMet routes end up Downtown (see this for details – feel free to play around) – and a whopping 60% of routes within the city of Portland do. Chicago, another classic example of a downtown-focused system has 36% of it’s routes converging in the Loop. In the pre-Covid days, Downtown Portland was the office job center with garish prices on parking – making public transit more attractive. TriMet going all in on this is evident if you take a quick look at the major capital projects undertaken or planned since it’s inception:

- The Original MAX Line (Banfield Light Rail project) – serves Downtown

- The Westside MAX Line Extension – serves downtown

- The Yellow MAX Line – serves downtown

- The Orange MAX Line – serves downtown

- The failed SW Light Rail Corridor – serves downtown

- The FX Bus service – serves downtown

This model was largely predicated on getting downtown commuters out of their cars, and onto public transit. But what this model really lacks is offering true intra-city connectivity. When downtown is pulling every bus across the river, it makes it painfully slow and difficult to travel North/South in the inner parts of the city – and this is a problem that TriMet needs to do so much more to address.

Quick aside – I’ve read a lot of official TriMet documents and plans lately, and I just feel like they are gaslighting me:

How does this grid of bus lines really look? Here are the routes of the 70, 71, 72 and 75 – the only buses that really qualify as cross-town service without a trip downtown.

And while this looks vaguely grid-ish, the 70 and 71 (first and third routes east of the river, south of I84) have just terrible schedules. The last full run of the 70 on Saturday evening is at.. 5:17 PM. No sane person can rely on that kind of schedule! Good luck getting from your apartment in Brooklyn to the airport on the weekend!

A Critical Analysis of TriMet’s Stated Purpose

I’m on board for lots of this, but I want to talk about my beef with the purpose of “easing congestion”. You could write a book about the history of fighting traffic congestion in American cities, but everyone these days frames congestion as bad. State Department of Transportations funnel billions of dollars into freeway widening projects, cities have built entire commuter rail services to ease congestion concerns for downtown commuters, and transportation planners the world over tout the economic benefits of less traffic.

All of this is an incredibly car-centric outlook on the world. “If only these poor cars sitting in traffic could flow freely, think of the economic gains!” is a common refrain. When a transit agency engages in this, they lose the thread on what transit is, and why it’s useful. Yes, it’s nice to get downtown in rush hour on transit – but the benefits shouldn’t be primarily considered as traffic relief. If it is, then the primary benefactors of the transit trip are the drivers outside of it.

Public transportation is not and should not be considered primarily as a “congestion relief tool” – it is an entirely different (and better) way of interacting with your city. Learning the bus routes in Portland has made every one of my walks and rides more enjoyable – it’s less daunting to explore when I know I can get back home on a bus for $2.50. Understanding the history of the network has led me to conceptualize the city in an entirely different way than I did as a driver – it’s way more interesting to experience a commercial district with an understanding of its history as a streetcar stop. And I’ve saved a ton of money doing all this to boot (which is a big plus when you quit your job 3 months ago and have barely started looking for a new one). Using 20% of your value statement to cater to downtown car commuters is banal.

TriMet and Equity

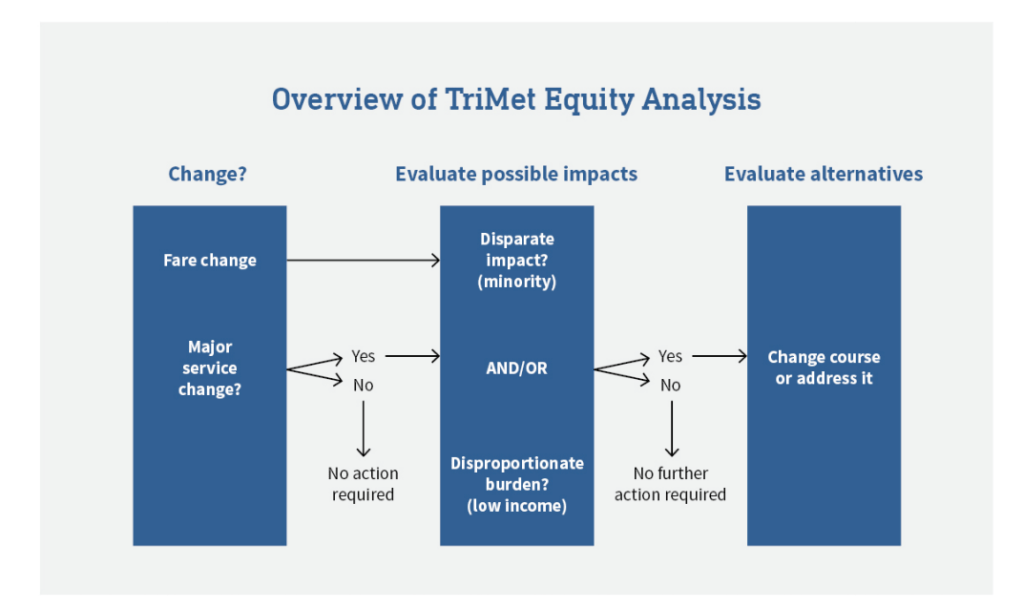

In the new bus service proposal I alluded to earlier, TriMet makes sure to center equity as a driving force in the decisions being made.

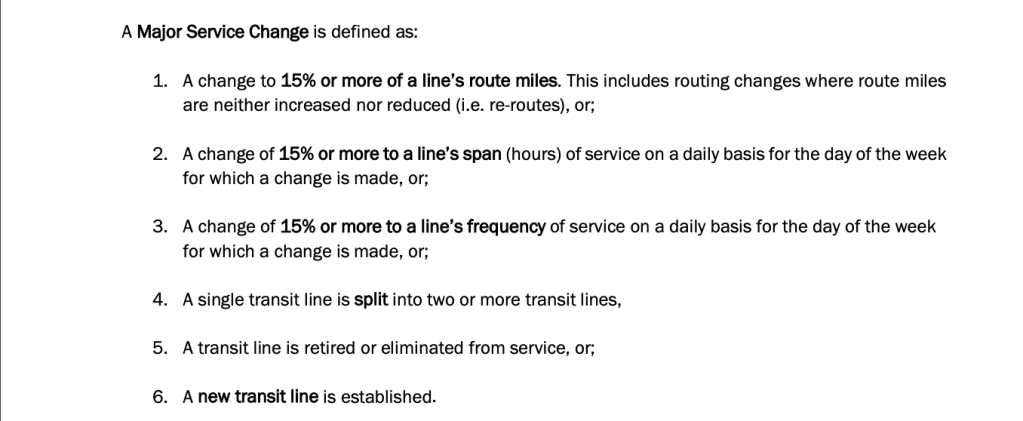

“Major service change” is necessarily an arbitrary metric – but by focusing on “15% of a line” I think there is a good possibility for shenanigans to happen. For starters, 15% is a huge change. If a bus runs from 6 AM to 10 PM (16 hours) a less than 15% change in would look like cutting service back to 6 AM to 7:45 PM (13.75 hours). And more importantly, any analysis here is predicated on the assumption here that the current service is appropriate and good. As far as I can tell, as long as planned service cuts stay below 15%, successive cuts to a line would not preclude any major service change analysis.

You can see this by looking at historic timetables for routes (shoutout to the wayback machine). The #70 ran 47 buses on Saturday southbound in 1997 (between the Rose Quarter and Milwaukie) from 8:51 AM to 10:10 PM (13:19 span), while the #70 now runs 30 buses on Saturday southbound from 9:02 AM to 7:26 PM (10:24 span). This is a massive loss of service – 36% fewer buses, with a 23% loss of span, but since it has happened piecemeal over the course of 25 years it doesn’t really register. Of course it’s entirely fair to hold TriMet to this level of scrutiny – the point is not to say that TriMet needs to replicate the best service schedules on all lines at all times, rather to point that this method is prone to a “death by a thousand cuts”.

I also want to spend some time considering something assumed here: Rich people don’t need good bus service. Implied in this, is that they can just drive! And while this may be literally true (wealthy people often have much greater access to a private automobile), it doesn’t mean it should be this way.

Public transportation already faces a lot of “only for poor people” stigma, and this intensely geographic way to consider equity misses the forest for the trees so to speak. It further solidifies long-standing class divides on neighborhood lines, while reinforcing car superiority. And in the long run, TriMet has a lot to lose by reinforcing these attitudes. In today’s constrained budget, the proposed changes are mostly good – but I think TriMet should be more careful with the way they frame things.

A Case Study – The Transit Mall

In 1977, TriMet opened the Downtown Transit Mall – two one-way couplets on 5th and 6th Ave that were bus only. This was done for two reasons – one to speed service up by removing private automobiles (thus making bus service more reliable, especially in rush hours), and to simplify the network downtown by focusing all service onto two paired streets.

When the mall was rebuilt in 2007 to add the new MAX Green Line, the Portland Business Community lobbied Metro and TriMet to add both on-street parking and through lanes for private vehicles to the transit mall along it’s entire length. Citing data from a consultant gathered over about 20 years, they noted that occupancy rates were about 10% lower on 5th/6th as opposed to 4th/Broadway (the nearest parallel streets). However, it’s obviously more complicated than this – with 4th and 5th having 77% and 76% occupancy respectively, and Broadway and 6th having 87% and 68% respectively.

I find it absurd that anyone would take this study seriously – Broadway is the premier commercial street in the entire city! It makes no sense to compare it to 4th, 5th, or 6th. It seems to me like this entire decision probably hinged more on a survey of business owners and managers on what “improvements” would help them most. Shockingly, 61% said automobile access; with 48% saying on-street parking as the top priority.

Pay no mind to the fact that downtown Portland has a huge amount of automobile access, with tons of structured parking and lots within a one block walk; this small number of business owners was able to make bus service in the entire city worse, all to serve some perceived “boost to business” because people could drive right to their doorstep. And it’s not an exaggeration to say bus service in the entire city is worse because of this – cars continually get in the way of buses on the transit mall now, and when you run nearly every single bus in the network along it, those little delays can cascade and add up.

Final Thoughts

All of this is somewhat frustrating, but I still think TriMet is among the best public transit providers in the US. They provide good bus service, and while the MAX isn’t exactly “express” a lot of the times, I love having an extensive rail network that has service on it. I think most of my issues with TriMet could be extended to public transit in the country in general, and stem from a much deeper cultural capitulation to the car than one regional transit agency should be expected to fix.

But I still think it’s worth critiquing them – not because I think they are some awful public agency, but because I think they are so close to having an excellent network of services. With marginally better bus service, and a few well chosen capital projects for the MAX, I think Portland could rival just about any other American transit city this side of the Hudson.

My priorities for TriMet:

- Express MAX service from Hillsboro to Goose Hollow. The current travel time of 45 minutes is just brutal – especially when the drive is like 20. A good timetable can make express trains on a corridor feasible even with just two tracks – CalTrain currently does it from San Jose to San Francisco.

- Grade separation for the MAX through downtown/Lloyd Center. As bad as a 45 minute trip from Hillsboro to Goose Hollow is, it’s a 21 minute ride for the 2.7 mile trip between Goose Hollow and NE 11th – that’s 7.7 miles per hour. A tunnel or elevated viaduct with a dedicated river crossing should be TriMet’s first priority.

- 15 minutes isn’t frequent enough. TriMet has pegged itself to “Frequent Service = 15 minutes or better, most of the day”. I could write a whole bit about how this isn’t true, but I think it’s just not ambitious enough. Seattle has a whole tier of transit service better than this, operating ten minute headways on a large portion of their bus network.

Thanks for reading, more to come later about whatever is bouncing around my mind. Probably somethings more about walking than transit and urban planning.

Leave a comment