Recently, I stumbled into a Metro’s “Regional Transit Strategy” rabbit hole. And now I have to rant about what it really means for a transit service (and system) to be “high capacity”. For the blissfully ignorant, Metro is the regional government in Portland (that doesn’t even cover the entire MSA!) which is a primary disbursement source of federal grants, as well as a centralized land use/transportation planning body. For the record, I think they do plenty of pretty good work. But I have a bone to pick with them today.

This was actually all prompted by a throwaway comment in a Vox article (that I found on the BikePortland Monday Morning Roundup) referring to the DC Metro as a “legacy system” (which it’s not! It was completed in 2001!). But it got me thinking, so let’s dive into an esoteric little discussion on what it all means.

In this update on our regional transportation plan, Metro says a few things that I think are worth dissecting

- High capacity transit is public transportation that moves a lot of people quickly and often – think light or commuter rail or bus rapid transit

- Division Transit – the regions first bus rapid transit line – will open this September (2022)

- Fewer cars on the road leads to less air pollution, more physical activity, less time in traffic, fewer crashes, and more reliability for moving both people and goods.

It’s instructive that Metro doesn’t mention the highest capacity transit options (maybe people would be confused if Metro talked about a metro though). The cities that move the most people on public transit always have fully grade separated, “heavy” rail systems. The New York Subway, the DC Metro, and the Chicago L were the busiest systems in the US pre-Covid, and are the gold standard for actual high capacity transit domestically. An eight car train on the DC Metro can carry about 1,400 people. A ten car train on the NYC Subway can carry about 2,000 people. An eight car train on the Chicago L can carry about 900 people. A two car MAX train in Portland can carry around 330 people.

Factoring in how much more frequently a subway-style service can run, the busiest lines on the true rapid transit systems can move an order of magnitude more people – the F train in New York has in the neighborhood of 190 trains per day, with a total capacity of 380,000 people (per day per direction). The Green Line in DC runs about 100 trains a day, for a total capacity of 140,000 people (per day per direction). The Blue Line in Chicago runs around 150 trains a day, for a total capacity of 135,000 people (per direction per day). The Red Line in Portland runs about 75 trains a day, for a total capacity of around 25,000.

I don’t know how to say this other than that’s between 5% and 18% of the capacity of a proper rapid transit line. Which is bad! And while New York is an exceptional system even by global standards, Chicago and DC are maybe just okay in the grander scheme of things. Metro, Portland, and TriMet often to refer to Portland as having “world class transit” but honestly it’s just not true. The entire MAX system runs in the neighborhood of 410 total trains per day, giving a total system capacity of just over 270,000 people – less than one direction of one line on the New York Subway. Is that world class? Single lines of other domestic systems can move more people than our entire rail network!

What does BRT even mean? Well, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy has a scorecard, and I don’t think it looks great for the Division Transit Project. Considering that basically the entirety of the alignment has very few miles of bus lanes, there is no off-board fare payment, there are few (if any) intersection treatments, there is no level boarding, there is only one route, no local/express service, and it’s dubious to even call it rapid. The slowest scheduled run in terms of average speed is 11.68 MPH (calculated from the GTFS files TriMet publishes). Is a bus route that goes slower than a medium speed biker really rapid? Compared to the EmX in Eugene (which is good BRT for the US, but nothing close to what you would find in Latin America), the Division Transit Project is pretty laughable.

TriMet focused a lot on the articulated bus rollout in marketing the FX Service on Division – but what you may not realize is that Portland was the largest transit market in the US (and maybe the world) that didn’t already have articulated buses. It’s a bit ridiculous to spend $175 million (even if it’s from the feds) when the primary benefit is a higher capacity bus that Portland really should already have running on its busiest routes. And honestly, if they didn’t slap the BRT label on this project, it would have been good with me. It’s just plainly not Bus Rapid Transit – especially by global standards.

Without actual bus lanes, it’s just disingenuous to call the FX Bus Rapid Transit, and seriously a bad joke to call it “high capacity transit”.

I’ve written some previously about transit existing to serve automobile related concerns but I want to talk about easing traffic congestion with transit specifically. Because I don’t think it works. In the US, where automobiles have just about saturated the market there is a functionally infinite demand for road space. Urbanists the world over have spilled ink about how freeway expansions don’t fix traffic in the long run. But to get to why I think transit doesn’t solve traffic, we need to understand a concept called “Induced Demand“.

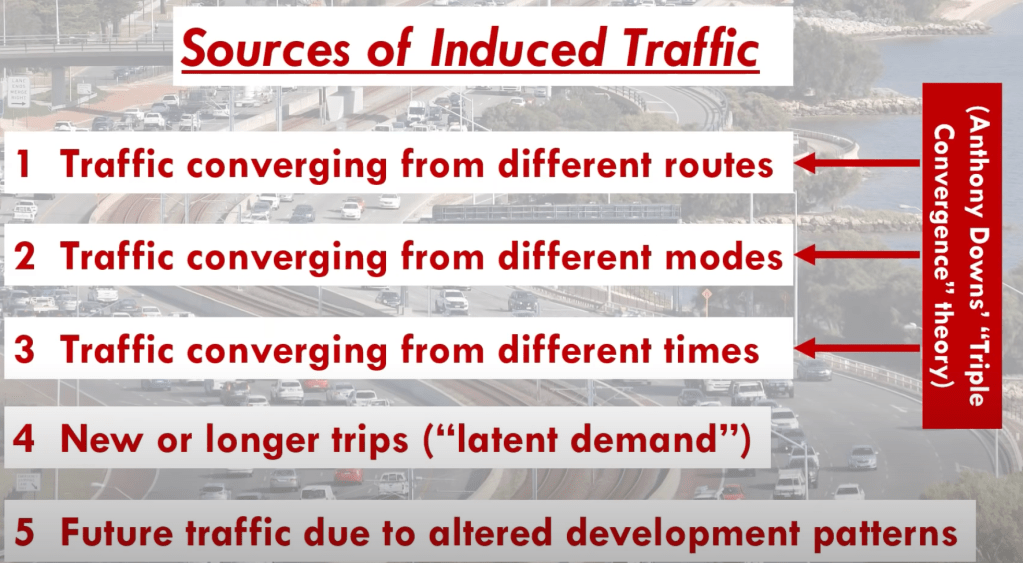

Traffic is often referred to in roughly liquid-like terms. Vehicles “flow” at given rates, so it’s tempting to conceptualize roads as pipes. When you widen a pipe, it can take in more water, and your capacity problem has been fixed. But when you widen a road (to alleviate congestion), the capacity is “used up” by other people who converge from a variety of sources (see below).

But this same logic should apply to transit projects as well! If a transit project is successful in removing 1,000 cars from the road in the peak hour we should expect them to be replaced by one of the “Sources of Induced Traffic”. When public agencies push the idea that “transit reduces traffic”, the long-term result of this is public distrust in the agencies when the traffic reduction ultimately doesn’t come. And this is bad of course, but it’s also bad because it misses the forest for the trees.

Transit is great in and of itself – it offers a different and better way to get around than driving. Riding the bus is a relaxing and enjoyable experience (most of the time), and riding trains is even better. Riding a real high capacity rapid transit service – with no traffic at all is incredibly reliable (and safe). Traffic is the result of a “tragedy of the commons” like experience – individuals overusing a resource (roadway space). Transit can only solve this by offering and entirely different source of mobility that is disconnected from the hectic, individualistic roadway system.

Ultimately, does it matter if our regional agencies blur the line on what high capacity transit is? I think it really does. Spending our precious resources on fancy stops for what essentially is a regular bus service instead of an actual high quality BRT service ultimately is very bad for the transit rider. That money would be better spent on doing something about the existing capacity constraints on the MAX – like the ancient bridge which carries all 4 lines (no, the Orange line and the Yellow line are not different services despite what TriMet would have you believe). Or grade separating the stretches through downtown (preferably elevated!) to allow for longer trains – since trains are currently sized to fit within a single downtown block (~200 feet long).

But beside the opportunity cost, when Metro and TriMet “completed” the BRT on Division what did it mean for the future of the corridor? Will they be unwilling to put money towards something better in the near future because the “high capacity corridor” has been “addressed”? I mean I don’t have any proof, but it’s reasonable to say they will not. And that is disappointing – especially when the corridor in question (Powell) is still dangerous, too wide, and right next door.

All of this makes it hard to be optimistic about transit in Portland. Of course I’ll keep riding the bus and trains. I enjoy it, I really do. But I don’t enjoy my regional public agencies acting like I don’t know what actual Bus Rapid Transit is, or that I’ve never heard of a subway. High capacity transit exists, but you’ll have to look elsewhere to find it I’m afraid.

Leave a reply to cityhikes Cancel reply