In another life, I was a road tripper. An honest to god “sure I’ll drive from Madison to Portland and back two and a half times in less than a year” type of guy. I mean I once drove more than 18 hours in one day (Portland to Bismarck, ND). Seeing National Parks was always a big part of this – I wanted to see “America’s Best Idea” for myself. And look – it was beautiful. The time I spent in Mount Rainier in October of 2020 was maybe the most beautiful experience I had ever had in my life. It galvanized my “I need to move the Pacific Northwest and explore it” in more ways than I can really put into words.

And really, the “Great American Road Trip” is an integral part of the American mythos. “Go West, young man”, see the national parks! Of course, you’ll be using America’s other “greatest investment” – the Interstate Highway System (I do not endorse that sentiment!) – to get there. I mean, how else would you get between two disparate parts of the country? Surely driving is the only way!

It Wasn’t Always This Way

The original interstate highways were the railroads. It wasn’t all butterflies and roses (the phrase the “wrong side of the tracks” didn’t come from nowhere), but most of the most famous National Parks were originally accessible by train. Some were functionally created by railroad companies looking to boost tourist (Great Northern did this with Glacier). Maybe it’s obvious, but it’s a point worth dwelling on: National Parks tourism predates the automobile.

It’s important to note that the railroads in this era were not “public transit”. They were for-profit companies who ran passenger service as part of a profit-making enterprise (at least initially – more on that later). And in the gilded age, the scenic beauty of Yellowstone, Glacier, or the Grand Canyon would have been far too expensive for the typical working-class person. It cost almost $10 to go between San Francisco and Los Angeles in 1937 – when the average hourly wage was around 45¢/hour. That same* ticket today is $54 on Amtrak, but with prevailing wages in the $17/hour range, you would have to work just over 3 hours today to afford that. In 1937, it would have been 22.

*technically you can’t get directly to San Francisco, since Amtrak has never served the city directly**. But it’s probably $3 on BART from Oakland, so close enough. If you want to recreate the original Southern Pacific route, transfer to Caltrain in San Jose – but that’ll cost more than BART.

**Okay technically between like 1977 and 1979 Amtrak operated Southern Pacific’s “Peninsula Commute” route from San Jose to San Francisco, so it would have been possible at one point. But not anymore, and you still would have had to transfer in San Jose.

I won’t turn this into an Amtrak history lesson (unless you really want me to), but a primary reason for the creation of Amtrak in the early 1970s was a “get out of passenger service free card” for the railroad companies. See, in the time between 1870 and 1970 a little device called the automobile took a hold on the hearts and minds of Americans everywhere (with definitely no foul play from GM and the like!). Passenger service was down (since the Federal Government had just spent $500 billion on the Interstate Highway system) so good old Richard Nixon devised a way to relieve the railroads of their obligation to provide service – not to create a public transit agency.

Because of this weird history, Amtrak has not really operated like a usual transit agency. Making a profit has had an outsized focus for the agency for years, rather than providing a quality service for Americans. Railroad tomfoolery or not, route cuts from budget constraints have plagued the agency since its inception. This means fewer trains taking the scenic route and fewer rural towns connected to major cities. The 5th most populous city in the country gets zero trains per day, and only two National Parks* are directly served by Amtrak (Glacier and New River Gorge).

*three if you count the Saint Louis Arch. Three more are served by other trains (Glacier Bay, Denali, and Indiana Dunes) owned and/or operated by the states they are in. More on that later.

How Did We Get Here?

In the 1950s, it became evident that the National Parks Service had an infrastructure problem. Mission 66 was the grand plan for the NPS to modernize its facilities for the cost of $1 billion, just in time for the 50th anniversary of the organization in 1966. Of course this was the 50s, so that meant expanding parking lots, widening roads, and generally making sure the motoring public could get to parks without too much trouble. Following the Robert Moses model of park development certainly has allowed many millions of Americans to see the parks – but was that a price worth paying? To answer this, I think there are two ideas worth discussing.

Let’s start with a pervasive idea in American culture – that the automobile boom of the 50s and 60s was a fait accompli, rather than the result of political choices (many of which turned out to be incredibly unpopular). In this brief article about Mission 66, the NPS themselves presents the idea that “[After WWII] the availability of affordable cars, increases in income, and better roads combined to spur automobile-borne tourism”. While these are true statements, I think it still represents an automobile fatalist view of park tourism. And this fatalist view would not have come about if not for Mission 66 itself.

Without the $1 billion spent on automobile-focused improvements, it’s possible the NPS wouldn’t be the beloved institution that it is today. But it came at a cost to the natural world that can never be undone. Every acre of park “developed” is an acre of park that can never be restored to its natural state. Given that the most famous and popular parks cite congestion and overuse as primary concerns, I think it’s fair to say that the legacy of car-focused development at National Parks is a mixed bag at best.

Secondly, it’s worth discussing if automobile focused tourism really results in an experience worth its salt. At the 11 most visited parks, only about 13% of visitors who stay overnight do so in the back country, while about 15% camp in RVs (NPS data can be found here). Look, I’m not here to get on a soapbox about how much better back country camping is than RVing – not everyone is physically able to back country camp. But in my experience, one trip to the back country is worth at least five in the front country.

But physical ability and backpacking aren’t the only things keeping visitors on the developed path. The NPS says “most” visitors stay within half a mile of the developed areas (at Yellowstone). It’s all about scenic drives, getting pictures at famous viewpoints, and taking a short little nature hike. The culture of National Parks tourism is still centered around the automobile, and if you already have a car at the park – well you might as well do that little drive around to see all the sights you can.

I would argue this isn’t a good way to experience nature though. The beauty of a back country trip comes more from the journey than the views themselves. You may get rained on, you may run into a bear after 11 hard miles on the trail, and you may feel emotionally drained at even the thought of walking another step but the rewards are indescribably sweeter after a rigorous physical (and emotional) challenge. Nature should be experienced on foot, and the National Parks Service needs to find ways to promote that.

Is There Another Way?

Public transportation has two huge benefits over automobiles when it comes to National Parks. Firstly, if well implemented, it can massively reduce automobile congestion. If old Johnny Hiker wants to do a day trip to his local park, and can take the bus with 20 other like-minded citizens that’s 20 fewer cars on the roads in the park. Which benefits everyone – it reduces congestion for the motoring public, it gives Johnny Hiker the opportunity to socialize with like-minded citizens on his ride into the park, and it reduces the need for expanded roadway facilities in the parks themselves.

Secondly, it allows for the Parks Service to manage use (and overuse) in a less intrusive way. Buses can be scheduled and controlled in a way that just isn’t possible with automobiles. If well managed, this can allow for crowd management without the timed permits or explicit quotas (which are unpopular). Because the roadway capacity freed up by the bus passengers is likely to be taken up by more motorists, it’s likely that quotas and timed entries may still be needed eventually. But to start, both crowd management and congestion relief are possible with a well run transit service.

Is This Possible Now?

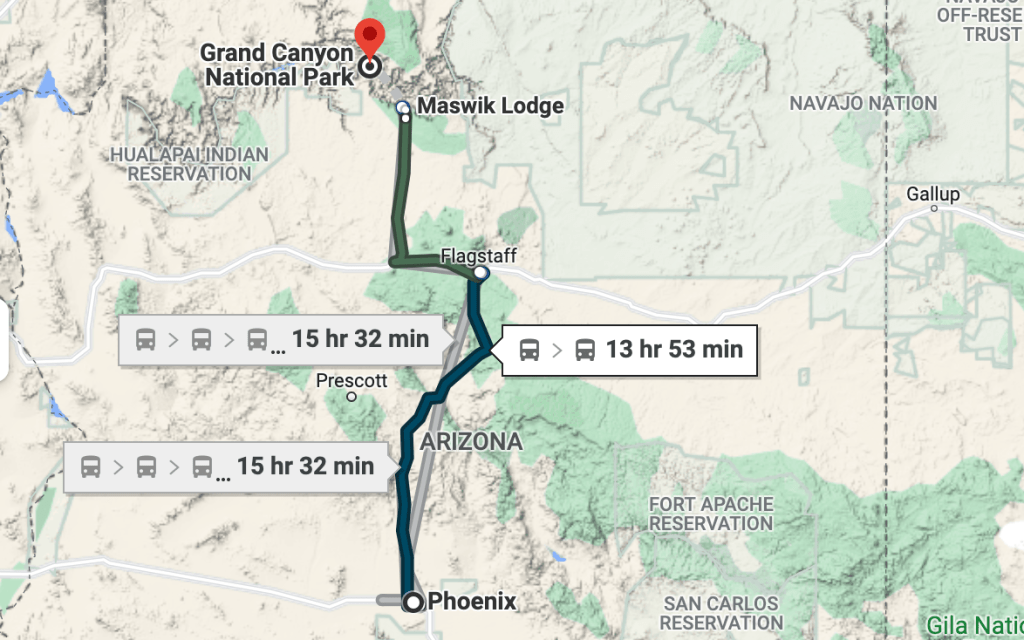

Not really. Only 17 of the 62 major National Parks are even nominally accessible by transit, and most of these are truly nominal connections. Some of them are good – Indiana Dunes has 12 trains a day (each way) from Chicago for less than $10 – while most are not (a Greyhound trip to a town three miles from Shenandoah is one of those 17). YARTS provides genuinely good service to Yosemite, and Clallam Transit runs buses to Hurricane Ridge in the summer. But there is serious amount work to be done for a coherent transit system.

You can ride transit to some of the National Parks, but I don’t think it’s fair to say that there is a transit system that the NPS taps into. Even Glacier, which has perhaps the highest profile transit connection – owing to the history and the current service – has somewhat limited information on arriving via transit, and relegates service between the park and train stations to a seasonal paid service by a third party.

A Crazy Idea

Greyhound is going bankrupt, and American intercity bus transit is seemingly dead in the water without public investment. The National Parks Service should run an intercity bus service in the same vein as Amtrak. I get it’s a wacky idea, but picture if you will a beautiful old Art Deco Greyhound station styled in Southwest colors gracing the rim of the Grand Canyon. Who could say no to that?

Seriously though, subsidized bus service to National Parks is a public price that is worth paying 100 times over. The vast majority of the investment has already been made – parks are not cheap to maintain and operate, and the roadway infrastructure is already there. Gating “America’s Best Idea” behind car ownership is a serious barrier to entry (and is a major reason that I myself still own a car) that disproportionately affects the poorest people in the country – and this is wrong on its face. The money exists to fund things like this – just take a look at how much is still being spent on freeway expansions – let’s channel it into something actually useful.

The National Parks are at a crossroads. They can either double down on car-focused infrastructure, capitulating to the public desire for unfettered automobile access to even the most remote and beautiful places on the continent. Or they can take the road less driven – towards a more sustainable future on the backs of the humble coach bus.

Leave a reply to Reflections On Car Free May – City Hikes Cancel reply