As you may know, I’m something of a Wisconsinite. And I was in the middle of writing a tweet up when it occurred to me that I should flesh out my thoughts on high speed rail in my home state. This may seem a bit odd, since I live in Oregon for now and the foreseeable future, but looking at old timetables struck a nerve – so here I am.

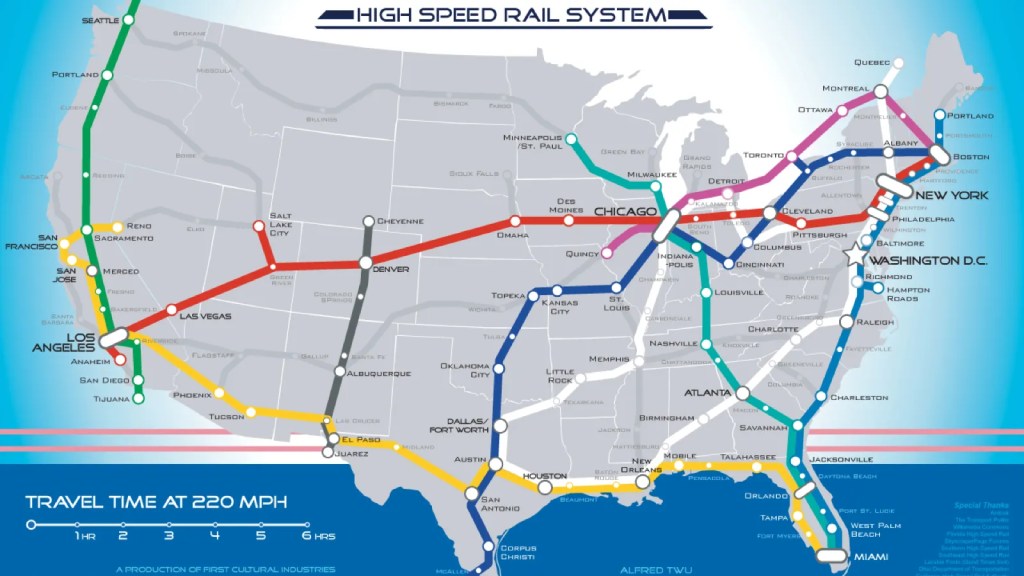

I’ve seen a ton of high speed rail maps, from the infamously bad one to many very good ones. And while I have thoughts on all of them, I find it frustrating that they are just lines on a map. I – and surely dozens of others – want more details on the specifics of each routing. So I’ve got a fantasy of map of my own to share, but before we get into that – a bit of background.

What Even Is High Speed Rail?

Well high speed rail doesn’t really have just one definition, but generally a train service that runs at over 200 kph (122 mph), or more stringently over 250 kmh (155 mph) qualify. It typically is electrified, though you could probably run a diesel service at high enough speeds to qualify. But it should be electrified!

Generally, when you mention high speed rail, the service that comes to mind are “Shinkansen” style services – literally “new main line” in Japanese. Without going too far off the depend of Japanese railway history, the primary reason that the Shinkansen was built rather than upgrading existing lines was technical – relating to Japan’s mainline railways being too narrow a gauge (the distance between the rails) to allow for the speeds desired. Additionally, there are further regulations on train speed outside the theoretical limits determined by curvature and gauge. In the US, tracks have different classifications which determine speed, and these speeds are limited by the physical track condition and the signalling system

Shinkansen style high speed rail is often necessary outside of gauge or signal related issues though, as maintaining high speeds requires tracks that are straight. Internationally, France, Italy, Spain, China, and Japan have all been in the Shinkansen camp building state of the art new lines to connect their largest cities. On the other hand, the UK and Germany have primarily upgraded existing lines – as has the US, as exemplified by the Northeast Corridor.

But even in Shinkansen style systems, it’s common for existing railway corridors to be utilized for the approach to stations. This is something I can pretend I remember with clarity from my handful of trips on high speed rail in Europe, with slower approaches to historic railway terminals.

Posing with a TGV back in 2014

What Approach Makes Sense For Wisconsin?

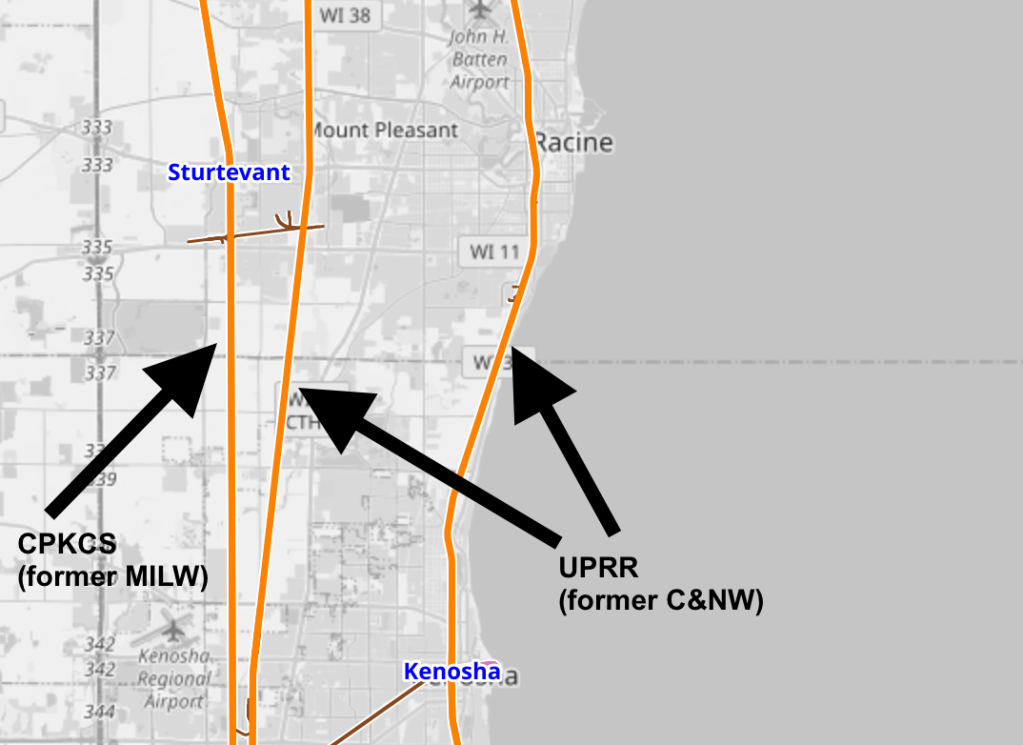

It depends on the location, but for the purposes of this post lets focus on just the section between Milwaukee and Chicago. Historically, three companies operated passenger service – The Milwaukee Road, Chicago & Northwestern, and the North Shore Line, with the latter operating as an electric interurban with the former being “proper” steam lines (the differences between interurban and “proper” main line rail are arbitrary and confusing). The North Shore Line’s tracks have largely been abandoned, but there are still three main lines between the two cities – owing to Chicago & Northwestern having two.

Why does any of this matter? Well it’s important to understand the specific location of each line. Currently, Amtrak runs seven daily round trips on the former Milwaukee Road mainline furthest to the west while Metra runs commuter service to Kenosha (bottom center) on the former C&NW mainline. As you’ll notice, the current Amtrak service bypasses downtown Racine and Kenosha – for one (or two) reasons.

The primary reason (I think) is that the Milwaukee Road tracks serve Union Station, while the C&NW tracks serve Northwestern Station (or Ogilvie Transportation Center if you prefer). Before Amtrak consolidated service in Chicago, there were six different railway terminals for intercity service (Dearborn, La Salle, Union, Northwestern, Randolph, and Grand Central) and Union Station was the preferred option – since it is a dual stub end terminal. Additionally, the Milwaukee Road ran faster service than C&NW did by about five minutes – though considering that the schedule now is slower than it was when the two carriers were competing for passengers, I’m not sure how much of a factor this was.

But despite all of these complications, it probably makes most sense for the Chicago – Milwaukee high speed rail corridor to focus on track upgrades, signalling, and electrification rather than building a new main line. It’s only ~90 miles between the two cities, and utilizing the existing railway terminals is the best option in both cities so any new tracks would need to connect at some point. Given the cost of land, this would likely be somewhere far out in the burbs which would also likely mean it would only be like 20 miles of new track.

So we have three lines to choose from, which one makes the most sense?

Option 1: C&NW Secondary Line

The middle line on the prior diagram would involve an 86 mile route, with a connecting track needed in both Chicago and Milwaukee to reach the terminal stations. Despite being ostensibly a C&NW main line, it likely never has seen significant passenger service. On the southern end in Chicago, it does not connect directly to Northwestern (Ogilvie) terminal and thus would need a connection where it crosses over the former Milwaukee Road tracks near Glenview.

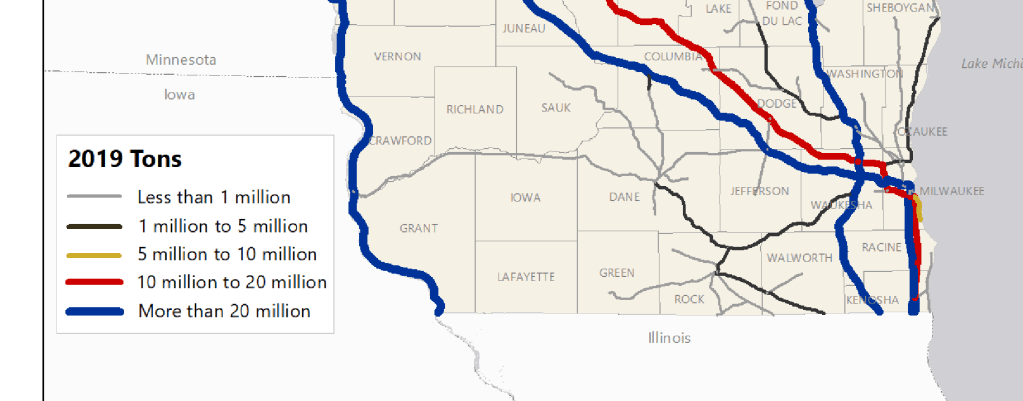

Probably because of its status as a secondary mainline, it doesn’t really much in the way of potential for stations in Racine or Kenosha and the need for multiple connections isn’t ideal either. It seems to carry more traffic than the old primary main line through Racine and Kenosha as illustrated by the map below (this line is the one in red heading due south from Milwaukee).

Option 2: Milwaukee Road Main Line

The furthest west line, currently hosting Amtrak’s Hiwatha and formerly of Milwaukee Road fame is also 86 miles long. It would not require any connecting tracks, but also does not directly serve Racine and Kenosha. It also has the benefit of being the most studied option, as the Wisconsin 2050 Rail Plan notes a goal of ten round trips on this route. However, that same plan does not mention much in the way of speed upgrades with the only mention being a “Sealed Corridor” for the Hiawatha – focusing on grade separation and speed increases up to 90 mph

This “Sealed Corridor” is still unlikely to beat the fastest Milwaukee Road trains from the 1940s – which routinely beat the scheduled 75 minute express services before the 80 mph speed limits came into affect post Naperville crash (1946). It’s disappointing that the best my home state can plan for is slower than we managed almost 100 years ago.

I would say this is the route that would also be most difficult to purchase. Its a key connection for Canadian Pacific Kansas City, while the two others are not nearly as important for Union Pacific (in terms of their networks).

Option 3: C&NW Main Line

And finally we have the C&NW main line, 84 miles long and directly serving both Racine and Kenosha. However, it’s not without its drawbacks for high speed service upgrades. For starters, the line passes through some of the denser parts of north Chicago and its suburbs. This might be good for a rapid transit line – and this line does parallel the Ravenswood CTA branch – but for a high speed line its not nearly as ideal. Additionally, there are some industrial uses, though not as many as there are for the other two lines.

But despite these issues, it’s also the option with the highest upside. You all should know my passion for smaller places and railroads by now, and returning passenger service to both downtown Racine and Kenosha would be a genuinely transformative thing – especially at the speeds we are talking about here.

Which One?

Ultimately, that’s a question of what really matters. Is it ridership potential, impact mitigation, or something else? I’d argue that what really matters is that the states of Wisconsin and Illinois have a way to purchase the line itself. While it is possible to run higher speed passenger service with a freight operator, it’s probably not practical for either of the primary main lines. Which means that the old C&NW main line (current UP) is probably the best choice.

Even if nationalization is my preferred route for public ownership of the rails, I do think the federal and state governments would be wise to start with a piecemeal approach for now. Milwaukee – Chicago is a proven success story for passenger rail travel – seeing consistent increases in trips per day throughout the Amtrak era and correspondingly high ridership. It also hosted upwards of 60 trips per day in the passenger railway heyday of the late 1940s (18 on C&NW, 15 on the Milwaukee Road, 27 on the North Shore Line).

In any case, the particular route choice is less important than the need to pursue purchasing one of them. If UP is only willing to sell the busier freight line in exchange for trackage rights on the CPKC (Milwaukee Road) line, then that would be an option worth pursuing. The larger point remains – the state needs to find a rail line it can reasonably purchase, and pursue that option, with a bond measure if necessary.

Putting It All Together

City Nerd has a few videos that talk about how the car is competitive at shorter distances because of the lack of time needed to get to the station, board, etc. and this is all fine and dandy. In an analysis like this, Milwaukee – Chicago is almost too short of a route (at under 100 miles) for a high speed service. But at top speeds of even 150 mph an express service could still reasonably make the 86 mile trip in 45 minutes – assuming about 20 total miles of 80 mph operation near the station ends, and a few extra minutes for good measure. I reckon that alone would be enough to induce quite a lot of additional demand.

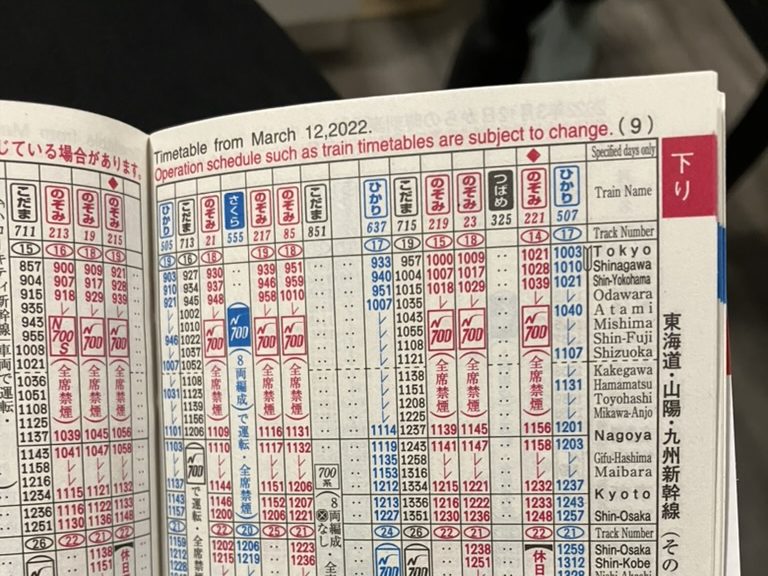

But there’s a larger point as to why high speed rail matters – and the speed is not really the point. The technical requirements to achieve high speed rail mean dedicated passenger service and electrification, which almost always means public ownership. And a publicly owned electric rail line can support service levels that even exceed our old friend the North Shore Line. Japan runs like 10 trains an hour on the Tokaido Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka!*

*technically, JR Central is now a private company, but the major Shinkansen lines were mostly built by the Japanese government in the JNR era. I don’t have time to go into the very interesting history of Japanese railway corporations unfortunately, and this is already my second tangent about the Shinkansen.

And I could go on about how a service like this would make Milwaukee much more desirable of a place to live for the Chicago commuter, but I don’t care so much about that. I mean I do, but I’m not sure suggesting that super commuters from Chicago bidding up prices in Milwaukee is something to be excited about. Rather, a high speed service between the cities would open the door for so many more opportunities for everyone.

Every God fearing Wisconsinite loves to rag on about FIBs and how much they hate the Bears – myself included – but frankly better access to Chicago matters. Chicago is more than just the home to bad drivers and bad sports teams, it has great museums, tons of theaters, and a fascinating history. And conversely, them having better access to Milwaukee matters too. More people seeing the Art Museum, City Hall, and the Mitchell Park Domes is a good thing for the city and the region. And given that Milwaukee has a unique civic history – including three long term socialist mayors – I think the city has a ton more to offer in terms of culture and history as well.

If there’s something I’ve learned from being away from home out here in Oregon its that the things that are different between Wisconsin and Illinois, or Milwaukee and Chicago are far less important than the things that are the same.

What’s Missing In Current Plans

I’ll conclude this post with a brief discussion of what the state of Wisconsin is missing in its current railway plan (which for some reason, is hosted on Google Drive? What are we doing guys?). Section 3.2 on Long Term improvements ought to be a good place to surmise the state’s priorities when it comes to passenger rail. Unfortunately, there are just seven subsections – all projects that I enthusiastically support. Extending passenger service to Madison, Eau Claire, and Green Bay are all projects worth accelerating, and if a commuter/regional rail service was to be spun up in Milwaukee I’d be there on opening day.

But there is a serious lack of vision for a long term planning document. Keep in mind, this is end-dated for 2050! Is the best we can hope for ten round trips between Milwaukee and Chicago, with one or two going to Madison, one to Green Bay, and a few to the Twin Cities; all on shared freight corridors? Other states – even with similar political landscapes like North Carolina – are aggressively pursuing public ownership of key rail corridors.

Again, even just a state-owned, electric railway between Milwaukee and Chicago with middling top speeds of 150 mph would fundamentally transform the state. It would also lay the groundwork for a much larger future system, leveraging Wisconsin’s particular historical context as the best path between Chicago and the Twin Cities. Upgrading the current Hiawatha service is a good idea, and something that can realistically be done in a few years. But we are fast approaching the limit of how much passenger service the corporate overlords in Calgary will accept on what is an extremely important line connecting their trackage in Canada to Chicago, the southern US, and Mexico.

Noted Chicagoan Daniel Burnham famously said “Make no little plans, for they have no magic in them to stir man’s blood”. And here we are offered an illustrative example of this. Wisconsin (and Illinois) could garner public support, and capture the imagination of a generation by doing a very straightforward and relatively cost-effective high speed rail project. But instead, our plans focus on minute upgrades, unlikely to be widely noticed or cared about even in transportation wonk circles. If we are serious about improving rail travel, it’s time to get serious with some modest plans. Starting small with high speed rail is still starting, and Milwaukee to Chicago is a slam dunk.

More on Wisconsin and high speed rail at a later date, but for now enjoy my own fantasy map of future passenger service in my home state

Leave a comment