Here in the US, everyone and their mother* has something to say about urbanism in Europe. The standard which bike advocates compare to is Amsterdam, and everyone seems to be finding a square in Barcelona or Paris to find car-free inspiration. To be clear, I find biking in Amsterdam and car-free spaces in European cities to be lovely. When I was in Europe after college, I fondly recall siting in the central square of Enschede, a Dutch city near the German border, having a few beers and chatting with dear friends. It was extremely nice, and probably was part of my inspiration in becoming someone who cares about cities.

*I’m not sure what my Mom has to say about all this

But it’s worth considering why it always seems to be Europe when we are looking to draw inspiration. At PSU, there are two study abroad opportunities for my program, one in Sheffield in the UK (led by a professor who formerly worked there), and one to either the Netherlands or Copenhagen (led mostly be TREC, the transportation folks and focusing on bike/ped related issues). I’m sure they are both wonderful, but they also cost thousands of dollars – something that grad students have in short supply.

I’m not here to advocate for something as narrow as the PSU MURP program having a study abroad opportunity at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver (okay but if anyone is reading this and make that happen I would sign up for it!). Rather, I want to consider what is lost when Europe is the only place for inspiration, and what the implications are for doing so.

Because urbanism (and planning more broadly) is about fundamental questions concerning how human society should be arranged, too much of a focus on any given area narrows what’s possible for those human arrangements. And while it’s generally accepted that the US and Europe have many cultural similarities, I think that framing diminishes how much we as Americans (in the US sense) have in common with our American (in the continental sense) neighbors.

How Native Americans Structured Society, and How it Impacted Europe

I recently read The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, which is centered around how typical assumptions about human society – namely the linear “progression” from simple childlike hunter-gatherer tribes to farming to industrialized societies is ahistorical and kind of racist, or at least demeaning to our ancestors who were fully capable of forming complex political societies. The entire book is fascinating, and you should absolutely read it for yourself, but some of the most interesting parts of the story relate to how European intellectuals reacted to the various ways that Native Americans structured their societies.

The central thesis is that Native societies weren’t some backwater of the world, waiting in squalor for the arrival of European notions of property to save them from their misery. Rather, their societies were structured in particular ways to solve particular problems relating to inequities that often come about in human life. Of particular note was the notion of freedom, with leaders generally having no way to convince anyone to do anything other than their own words. This was a wholly foreign concepts to most European intellectuals, and the Indigenous critique of European society heavily influenced the Enlightenment.

I think this is an important thing to bring up largely because the concept of freedom is a central tenant of American philosophy, at least in spirit. Identifying that concept as being a part of the cultural heritage of being American (in the continental sense) means that we should natural look to our own hemisphere for inspiration. The Enlightenment concepts that were foundational principles for the US would not have been possible without the influence of Native American cultures, and given that much of later European thought is grounded in this as well we ought to take American urbanism, planning, and city history more seriously.

Yes, Native Americans Built Cities

Some of this discussion is admittedly, a bit of a non sequitur. The cultural roots of concepts like freedom are not unique to the Americas, and many traditional European societies were non-hierarchical, eschewed profit accumulation, and had a strong traditions of freedom. But in the grand “story” of history from the Western perspective, the Enlightenment came about because of the superiority of what is now mainstream European culture and scientific reasoning rather than a complex exchange of ideas with many groups – ranging from Native Americans to China to the Arab World.

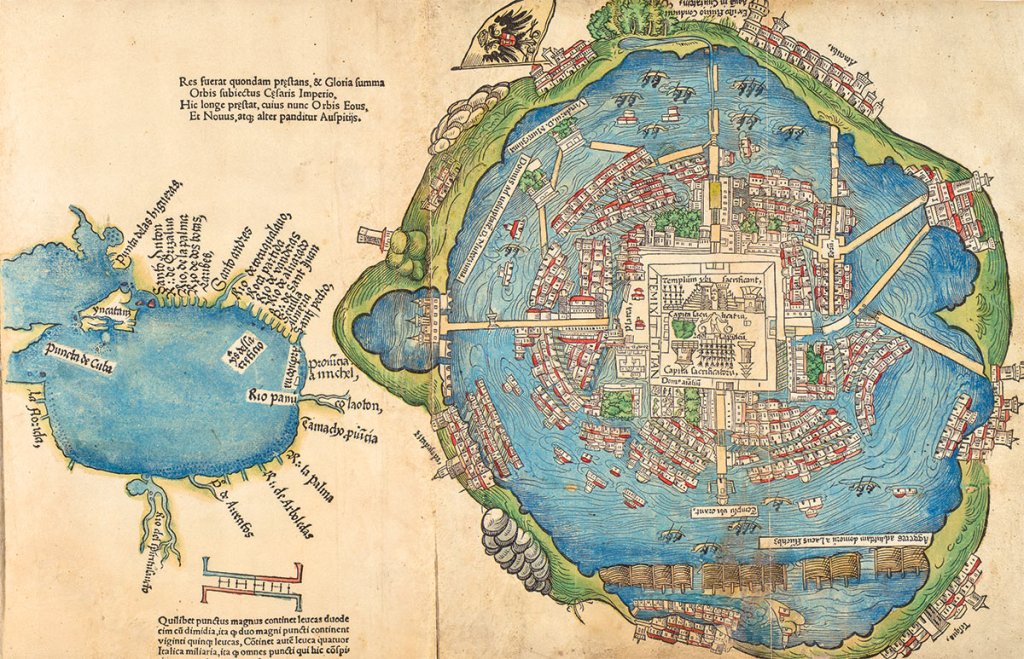

But back to the topic of cities and how people live in them, the Valley of Mexico has historically been home to many cities. Tenochtitlan housed between 200,000 and 400,000 at the time of the conquista, and was certainly planned around the social and economic needs of the residents. It was also in Lake Texcoco, and featured a dike system to contain freshwater for planting crops.

However, a few centuries earlier 30 miles to the northeast the city of Teotihuacan has a history worth understanding in more detail. Disclaimer that according to David Graeber and David Wengrow, speculating on the sort of city that Teotihuacán was to a specialist in Mesoamerican history and you’re like to get “a roll of the eyes and a resigned acknowledgement that there’s just something ‘weird’ about the place”. It rose to prominence sometime around 100 BC, and was abandoned by 700 AD leaving behind grand pyramids, which still stand today.

Notably absent from the site is any indication of a royal court, or fancy tombs, or anything that would indicate some level of aristocratic rule. Instead, it is likely best described as a self consciously egalitarian republic of sorts, though few specific details are known. Some of the primary evidence for this – and indeed at the heart of the mystery surrounding what sort city Teotihuacán was – is in a uniform and very widespread style of apartment, typically covered in murals and likely some sort of social housing.

In the Western canon, a republic is the sort of thing dreamed about by philosophers in Ancient Greece, briefly tried in Rome, visited again in medieval city-states, and the perfected in the US of A. Surely evidence of a republic-style city of 100,000 (or more) existing at the same time as Rome ought to be of interest to those who care about representative government, but instead Teotihuacán is largely seen as a site of Aztec mythology or an archaeological quirk.

I find Teotihuacan to be a fascinating place for a ton of reasons, but it really is a prime example of Native American urbanism, and ought to stand as an example of what’s possible in modern cities too. If a bunch of people in the Valley of Mexico using obsidian tools without domesticated beast of burden could build housing for all of their citizenry nearly 2,000 years ago, we ought to be able to do at least as much now.

What’s Possible For Our Shared Future?

The nuts and bolts of the archaeological record in Mexico is beyond the pale of what most people really care about when it comes to cities, but I think it’s important to have a wide understanding of how different societies have constructed urban life. So much dialogue in US urbanism tends to revolve around broadcasting a better life for city dwellers, but it’s not just European cities that have this. Of course, the lessons of social housing in Teotihuacan could have well been gleamed from Vienna as well – and with far less speculation.

Indeed, the story of Wiener social housing is also something I find extremely interesting – as it takes its roots from a left-wing government building social housing for the poor after the first World War. But it’s still important to have a broad understanding that there is nothing “special” about Teotihuacan, Vienna, or any other city that manages to create space for all its citizens. Rather, it “simply” requires the collective will to change. There is no hard and fast reason for a society to be structured in any particular way, and anyone claiming to do so is likely just broadcasting how they believe society should be structured.

And to me, this is ultimately what is needed for US cities (and many other cities the world over). It’s not so much that we need to learn design lessons, or “best practices” for zoning – the real thing to learn is a political lesson. Cities that manage to provide decent housing for all are cities which have some deeper level of self conscious egalitarianism guiding them. The people have to believe that everyone deserves the right to something like a place to live, and they have to create a political system that actually delivers that.

What’s unique about Europe relative to Mexico in American eyes is simply that Europeans have the freedom to choose their own political fates to a much wider degree. In Mexico, indigenous communities held ejidos as common land, and were constitutionally protected – something established in the wake of the ten year long Mexican Revolution. The fact that the US sat idly by allowing indigenous peasants in Mexico own land communally from 1920 to the signing of NAFTA is a strange quirk of history, but as the Wikipedia for NAFTA so clearly puts it “this barrier to investment was incompatible with NAFTA”. Would the US dare to claim that communally held social housing in Austria is a “barrier to investment”, something incompatible to free trade with the EU?

If we as a country are so worried about protecting the right for foreign investors to buy land from impoverished peasants in Mexico, it’s really no wonder that our cities almost uniformly reject large-scale social housing that would be accessible to all. This is all slightly off topic, but it sheds light on part of why Eurocentrism is so enduring – the US doesn’t do nearly as much meddling in European politics, so self consciously egalitarian social structures aren’t destroyed in the name of protecting foreign investment.

Public Transit Is Just Okay In Europe

On the topic of public transit, we simply do not pay close enough attention to China, India, and Latin America. Here is the World Economic Forum saying that seven of the top ten cities for public transport are in Europe, and none are in mainland China, India, or Latin America. Frankly, you can tell the methodology is fundamentally flawed just by seeing that Oslo, Helsinki, and Stockholm rank higher than Tokyo, but it’s even more egregious that Beijing is missing from the list. So let’s compare the Beijing subway to Helsinki.

| Category | Beijing | Helsinki |

| Total Length | 836 km | 43 km |

| Stations | 490 | 30 |

| Ridership (yearly) | 3.85 billion | 92.6 million |

| Ridership/Capita | 172.1 rides/person | 58.7 rides/person |

Wow, it turns out that Beijing is the busiest metro on the planet (or at least near to it) and moves 3x as many people in per capita terms and 42x as many people in absolute terms as Helsinki. Of course, it’s in China so that makes it scary for the folks at the World Economic Forum to call a success, since it was centrally planned by a nominally socialist country that participates in the global market. But of course, the study in question ranks Dallas, Texas higher than Beijing on the overall urban mobility index, and Beijing ranks just 27th/60 in public transit. Again, this is all in the context of having one of the busiest metros on the planet! Mexico City, home to the tenth busiest public transit system in the world, ranks 50th out of 60, and the study cites that they “Mexico City has not yet prioritized connected autonomous vehicles technologies” as a reason for doubt. Get a grip and leave the Bay Area for the love of God.

It’s difficult to understate my ire with this study. If your study ranks both Dallas (45th) and Houston (43rd) as places with better public transportation than Mexico City (50th), you should be fired into the sun. The worst ranked city in Europe for public transport, Dublin (28/60) ranks higher than the best ranked city in Latin America, Buenos Aires (30/60). Buenos Aires has commuter rail, BRT, and a six line metro with 90 stations and 57 km of track. Dublin doesn’t even have a metro! I feel like I’m losing my mind reading this list

While European cities tend to have good tram networks and good intercity connections, urbanist darling Amsterdam runs peak frequencies of 6 to 10 trains per hour on its metro and ranks as the 11th best city for public transport. Ahead of New York City (13th) – New York! You know, the city that’s known for the subway, where peak hour frequencies are like 20 trains per hour or more on busy lines. New York’s public transit system blows Amsterdam’s out of the water, and it’s not even close.

This report is pure, distilled, Eurocentrism (with a side order of Californian exceptionalism). If your metrics for public transportation manage to rank Oslo over Tokyo, Dublin over Mexico City, and Amsterdam over New York wrong doesn’t even begin to describe the issues. Purposefully misleading at best, propaganda at worst, this report perfectly sums up my issues with Eurocentrism in the English speaking world. A random person in a random Chinese city has a good chance of having better urban amenities than you do, but admitting that would mean admitting that parts of Chinese society are structured well – and that is an unforgivable faux pas.

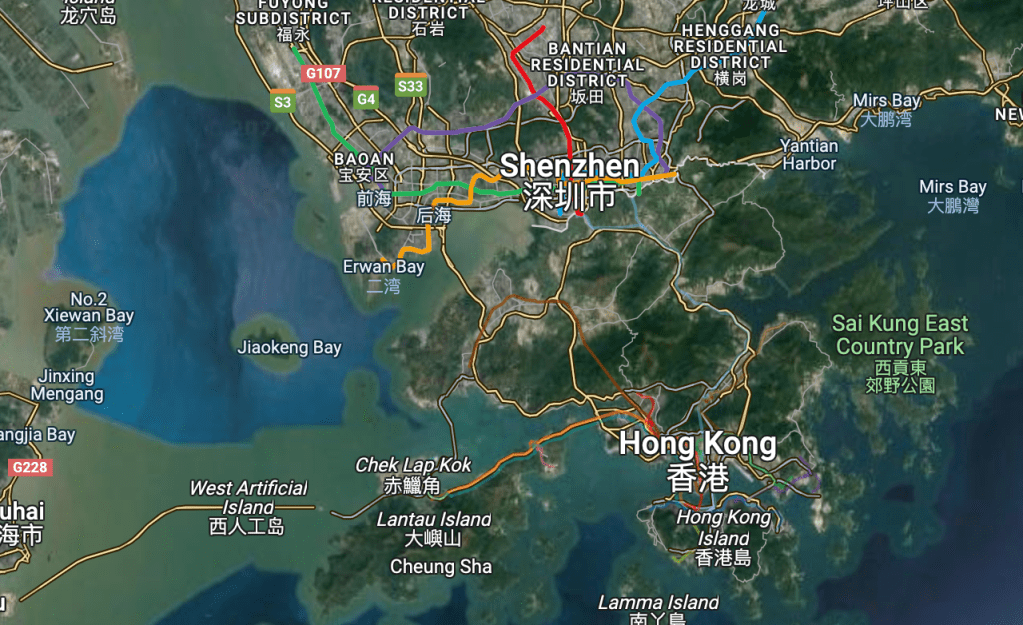

If you want a tip on if a ranking of cities is Eurocentric, also consider counting the number of European cities and comparing with the number of Chinese cities. In this report, there are 13 (or 14 if you count Istanbul) European cities, but only three Chinese ones – Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai. It’s extremely telling that Hong Kong, arguably the third largest city in its own metropolitan region*, is included while nearby Shenzhen and Guangzhou are excluded. Sure, it’s an important economic center, and it does have an excellent transit system, but I feel it gets included over its larger neighbors more because of its familiarity for western audiences.

*The Pearl River delta is a huge region, and Guangzhou would likely be considered a separate metropolitan area in the US. But Shenzhen is less than 20 miles from Hong Kong, and I think you can transfer between their metro systems. It’s hard to argue that they are really separate, but Shenzhen has ten million (!) more people than Hong Kong and is growing at a truly frenetic pace (+7 million between 2010 and 2020).

A few other things I just have to mention from these rankings: San Francisco is ranked #1 overall “thanks to a rich ecosystem of academia and entrepreneurs who have made the city a global hub for Mobility as a Service and connected autonomous vehicles technologies”. No wonder it’s such a bad list. And wow, San Francisco gets points because electric vehicles get federal tax credits and electric vehicles being able to use highway HOV lanes, visionary stuff right there.

Finding Inspiration Everywhere

Does anyone pay attention to the World Economic Forum? I sure don’t, but it’s likely that you may have seen this list, an article going over it was published in Bloomberg after all. And while the astute among you may recognize Bloomberg as fairly obviously a tool of US ruling class interests (it is owned by Michael Bloomberg after all), City Lab is a fairly respected outlet from what I can surmise in urbanist circles and some of what they publish isn’t quite so bad. To be clear, I’m not really here to say that it’s some piece of Western corporate propaganda (okay maybe a little), but we should all be able to agree that citing a study with such obviously flawed rankings is bad practice.

There are tons of fascinating examples of things cities the world over do, so now I’d like to take you on a brief survey of a few cities that I think are excellent – but that you don’t really hear much about when people talk about great cities.

Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Guadalajara boasts three metro lines, or two light rail lines and a metro line depending on how you count things like this. Seeing as all of the lines are underground in the central city, and it gets metro levels of ridership (250k/day), I think it’s better understood as a metro than a light rail. But either way, it has a fairly good urban rail system, and is one of the original practitioners of Latin American Bus Rapid Transit – which is noted for being actually rapid transit (instead of whatever we end up with in the states pretending to be BRT). I think Guadalajara is an excellent example of how compact and urban looking most Mexican cities are.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

China as a whole is generally poorly understood by most people in the US, and I reckon if you asked 100 people on the street maybe three of them could locate Hangzhou on a map. While the city owes its historical prominence to its location at the southern end of the Grand Canal, Hangzhou is generally of note to urbanists because of its bike share – the largest in the world terms of number of stations and number of bikes. While China in the Mao era was noted for extremely high levels of bike ridership, with party leadership using “a bike in every household” as a heuristic for prosperity this has fallen out of favor as automobile use has increased.

Still, the Hangzhou bike share is noted for being popular among households with cars and if a Chinese city of 10 million can find a way to make cycling work, I’m hopeful for just about every city under the sun. Also of note, Hangzhou has 12 metro lines (despite Google only displaying 3) and had 2021 ridership of almost 900 million – more than every US system outside of New York. And of course, it has more than 500 km of track, with expansion plans for a further 160 km – all for a system that did not exist in 2011. If you want your mind blown, just go down a rabbit hole of Chinese metro systems.

Santiago, Chile

Santiago, like most cities in Latin America is quintessentially urban. Markets, train stations, markets at train stations, and a well-ridden metro system. It’s massive, sprawling, chaotic, and beautiful. I don’t really have much insight to offer other than it has a busy metro system – the fourth busiest in the Americas (after New York, São Paulo, and Mexico City) and that Chile is a fascinating country.

Istanbul, Turkey

While American commentators the world over exude joy over the latest car-free streets in [insert your city here], I see functionally no space dedicated to the humble bazaar. Maybe I need to break out of my English speaking bubble, but the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is pretty unfathomable – it’s both the oldest and most visited “shopping mall” in the world, a framing that feels a little strange. But still – 4,000+ shops over 7 and a half acres, it seems like you could spend an entire lifetime just exploring this one place.

Istanbul is arguably in Europe, but I am including because Turkey exists in a bit of a liminal space between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. It’s the quintessential crossroads, and Istanbul has been one of the most important cities in the world for as long as their have been cities in the world. And of course, it has a well ridden 11 line metro system with half a billion yearly riders, and probably the only trans-continental regional rail service in the world (if you buy that the border between Europe and Asia really is the Bosporus anyways).

Putting it All Together

At its core, all this is about dreaming bigger for our cities. If Karaj, Iran (metro population of 2.5 million) is building a proper metro system, why on earth can’t Portland too? A lack of global perspective will continue to cripple us if we do nothing about it. And while there are useful perspective to glean from Europe, I think it’s limited in scope. Like it or not, the US shares a political and cultural background that is just as similar to our kin in Latin America as Europe.

Furthermore, great urban places exist everywhere that humans have settled, in many places for thousands of years. Walkability, car free spaces, cycling, and great public transit is not something unique or endemic to Europe. Rather, it’s the natural state of being for humans in urban areas. To draw inspiration solely from Europe is ignorant at best, and [redacted] at worst. Every quasi-fascist Twitter account with a name like “Cultural Tutor” will post long threads about how “we need to return to Europe” for fairly surface level aesthetic reasons, and I think that urbanists risk aligning too closely with that societal current.

Again, great urban spaces are our shared human inheritance – even if we have temporarily ventured from the norm in the US to accommodate almost exclusively travel by automobile. Fixing the mess of the mid 20th century will require reusing and rekindling existing spaces, but there are far more places than just Europe to draw inspiration from.

Leave a reply to Japan Trip 2024: Cycling in Tokyo – Urban Adventure League Cancel reply