In the height of Covid, the Portland Metro region voted on a ballot measure to fund a new light rail line stretching about 11 miles from PSU to Tualatin. In part because of a well-funded opposition campaign from Nike, a global pandemic, and (presumably) a myriad of other reasons, the ballot measure did not pass. Some chalk this up to a regional rejection of light rail as a concept, some think it’s merely an blip in the radar of a transit friendly region.

For my money, it’s some of both – the broader Portland region has never really been all that stoked on funding light rail, even if planners generally have been. The original South/North corridor funding measure failed in Clark County, and the revised corridor failed in the Metro region (both in the late 1990s), while the Westside extension line failed a statewide funding ballot measure, before passing a local bond measure (this line perhaps represents the zenith of light rail support in the greater Portland area – the bond passed 70/30).

In any case, I think it’s best to not draw too strong a conclusion from any vote on a transportation funding package in Portland. They fail just as often as they succeed, and with seemingly no bearing on the quality of the project (both iterations of the failed South/North project were almost certainly a “higher quality” rapid transit project than it’s successor, the Yellow Line). And before we go further, the SW Corridor as it stands now is a “shovel ready” project, and as such any changes that require a new environmental impact statement (EIS) should be weighed against if the benefits outweigh the cost of basically starting from scratch.

So What’s the Big Deal With the Plan?

The light rail line was advertised as a 30 minute ride from Tualatin to PSU (my current institution). Before we go any further, it’s worth asking “is this any good?”

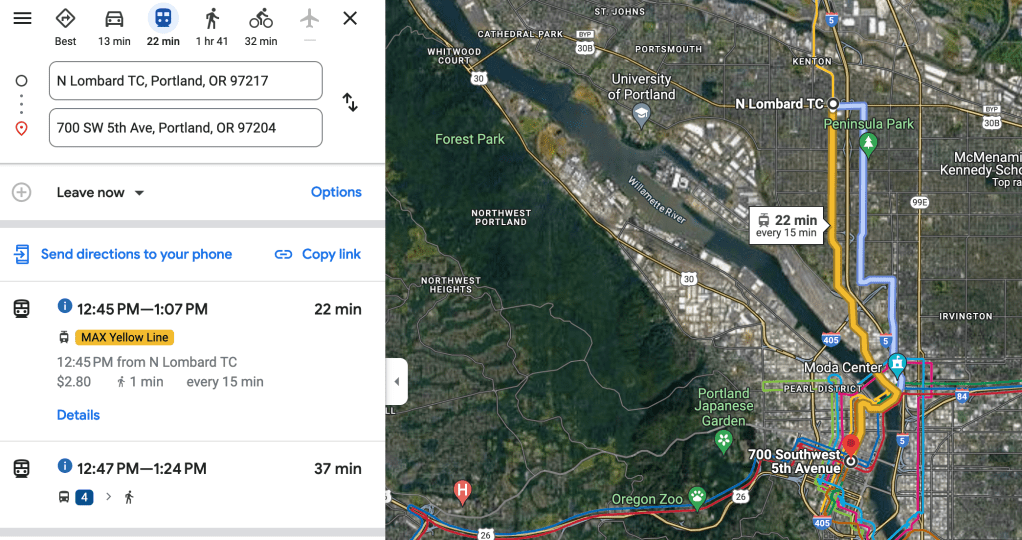

In short: not really. Right now (10:32 AM on a Monday), it’s an 11 minute drive from the terminus of the line to PSU. Sure, you’ve got to park too, but it’s not exactly competitive at 19 minutes slower. And here’s our first problem – designing a multi-billion dollar transit project aimed at commuters that fails to meaningfully speed up their commute. Even if we accept that this project has a good premise (we won’t accept that but humor me for a second), it sort of fails at the only thing it’s supposed to be doing.

Aha! But what about a future more-congested state of I5 you ask? Well, sure if you trust travel demand models that show a 30 to 40 minute trip in 2030, or 2040, or 2050. I don’t trust travel demand models, having worked with a particularly dubious one in some of my coursework last spring, but even if you’re willing to accept this then you still need to consider if it’s the best use of public transit dollars. Given that the 96 currently makes the trip from Tualatin to PSU in less than 30 minutes at peak times now (running express on I-5), the 12 makes the trip from Tigard to PSU in about 30 minutes at peak times now (running local on Barbur Blvd), it’s hard to see exactly how much better the transit experience would be for existing riders than it would be if we just spent money on running more buses (I know there are different funding streams, but you get the point).

Perhaps if you buy the big light rail pitch, that people prefer rail to buses, and thus if you build a rail project it will attract more riders than a bus then the project is worth. I won’t argue that premise, but it’s unclear to me why the rail option has to be so slow. Barely beating a local bus, while also barely beating an express bus stuck in I5 traffic just doesn’t really instill much confidence. I’m not particularly interested in the specifics of why the SW Corridor is slow by my standards – though it could most succinctly be described as “low top speed, too many stops”. TriMet limits light rail running on streets to the speed limit of that street, which ends up crippling the SW Corridor since it primarily runs along the median of Barbur Boulevard.

Why is it Always Light Rail?

Given that light rail is by it’s very definition lower capacity (“A transit mode that typically is an electric railway with a light volume traffic capacity compared to heavy rail.”), it makes a somewhat awkward candidate for the sorts of regional transportation projects we build in Portland. Former Portland planner, Ray Delahanty (aka City Nerd), mentioned in a video that I cannot find right now for the life of me that Metro has had a policy of pursuing light rail as a primary regional transportation solution for decades now. This has meant that Portland has gotten a slew of pretty good light rail lines, some of which are better substitutes for driving on a freeway than others.

Evidently, there are places where Portland’s light rail system works well for transit riders. Travel times from Beaverton to Downtown Portland are competitive with driving at all times – mostly due to very few stops and a fast alignment under the hills.

Likewise, Gateway to Lloyd Center does very well. It’s no surprise that these are the two most popular corridors on the MAX system. It’s not because they are well situated relative to dense land uses (they aren’t), or because they trains. The primary reason is that offer a service that is legitimately competitive with driving. The fact that they are trains probably doesn’t hurt, but plenty of places run bus service that puts the MAX to shame and they aren’t hurting for riders.

But in other places – like North Lombard to Downtown – the MAX is fairly significantly slower than driving (in a bit of traffic). There are good things about the Yellow Line, but given the fact that it’s currently the best* route for a transit expansion to Portland’s most important suburban neighbor (Vancouver) it’s status as a “Metropolitan Area Express” service feels a bit dubious.

*it’s only the fastest transit route if you’re unwilling to imagine a regional rail service using the existing BNSF corridor!!!

If we accept this as a fact – that speed is always a primary concern for transit riders – then we should not be too quick to always choose light rail for our regional transportation projects.

A Brief Tangent

One of my primary influences in thinking about transportation policy comes from a blog called “Caltrain HSR Compatibility Blog“. Every article is interesting, but the post about Metrics That Matter has stuck with me.

“The future of Caltrain is likely to hinge on the quality of the service provided”. This is true of all transit agencies, of course, but the 4 metrics used (average trip time, best trip time, average wait time, best wait time) are easily understandable, and derive themselves solely from timetables. Because of this, I think it’s a useful heuristic to judge the SW Corridor by.

An “In-Depth” Look At Travel Times

In the Caltrain HSR Compatibility Blog, blog author Clem Tillier spends a lot of time analyzing timetables and parsing out if they are any good. I had hoped to do this for the SW Corridor, but unfortunately the EIS has remarkably little in the way of actual schedules. In fact, despite spending far more time searching than I would have hoped, there is no documented timetable with the EIS at all.

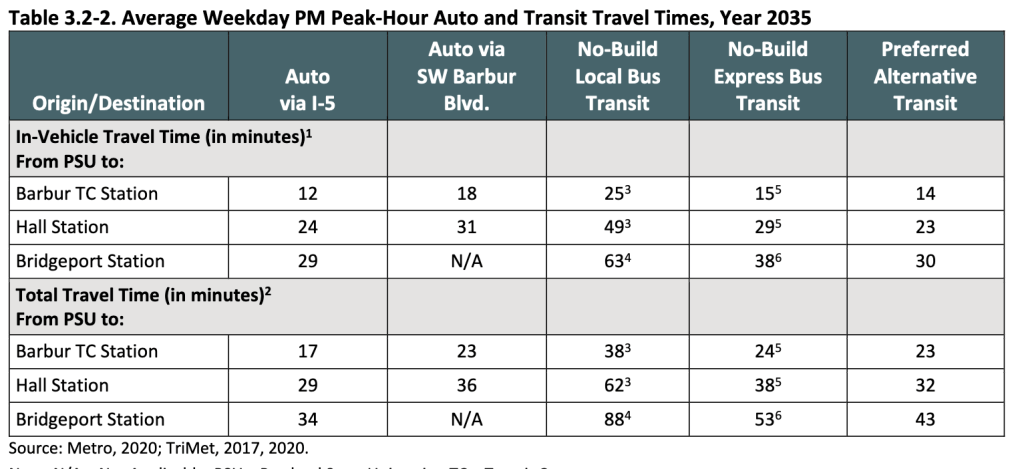

For a project whose stated purpose includes the sentence “improve transit service reliability, frequency and travel times, and provide connections to existing and future transit networks”, it’s a little frustrating that they don’t have a place where they can just put a schedule. The closest thing they have to a schedule is this table showing the projected PM peak auto and transit travel times (I found no similar table for the AM Peak).

But don’t worry, there are 14 parts for the 56 Appendices to Attachment B (transportation modeling – aka how to accommodate cars). Maybe I’m a sucker, but doesn’t it feel like there should be a schedule included? Also – for a project that advertised itself as “Portland to Tualatin in 30 minutes”, it feels mildly disingenuous to use the reverse peak travel time.

So instead of looking at official schedules, I had to make it up with a very ridiculous spreadsheet. What a shame! (You can have a look at it here). Using the “Metrics That Matter” post from the Caltrain/HSR blog, ODOT travel data (as a rough tell for relative demand), and a bit of cheeky physics, I was able to derive a rough estimate on travel times between each origin destination pair (for fastest trip), and then normalized those fastest trips to the average travel times in the table above. It’s a bit of a mess, but the point is to compare this light rail project to my personal favorite option (call it the “City Hikes Locally Preferred Alternative” if you will) – a high speed suburban rail line.

Suburban Rail Can Be Frequent

Surely the biggest gripe that most people have when talking about main line rail transit in the US is the lack of frequency on the few existing suburban lines. Even if there are some pretty good suburban lines in the US (Metra Electric runs ~3 tph from UChicago), the vast majority are peak-hour focused relics of a bygone era. So as ever, our attention should turn abroad for examples of places with similar land use patterns, and highly successful suburban rail projects. And for this, we should journey down under.

In the Western Australian metropolis of Perth, the Fremantle line runs 4 to 6 trains/hour to the southwest suburb of Fremantle about 12 miles away at the mouth of the Swan River in about 30 minutes. With 14 intermediate stops, this line functions in a broadly similar way to the proposed SW Corridor, just with faster travel times and more established neighborhood centers (as it is an old line). And Perth is about the same size as Portland at 2.3 million.

Heading east to Queensland, and you’ll find lines in Brisbane (population: 2.7 million) that have 6 to 10 trains an hour. And this is to say nothing of the extensive and excellent networks in Melbourne or Sydney. If the Portland-sized cities of Australia (a country with a very similar development history to the US) can manage a suburban rail network that puts the MAX to shame, it’s high time we start trying to emulate them.

And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Europe. Basically every large city (>300k) in the German speaking world has an S-Bahn with frequencies on the main trunk approaching every 5 to 10 minutes, and London suburbs like St. Albans see 6 to 10 trains/hour on the Thameslink. Portland is not as fortunate as many other US cities, and lacks a lot of legacy rail infrastructure that could support frequent suburban rail. The only N/S link is painfully slow and congested around Union Station, and doesn’t really serve key destinations – especially south of Portland.

But given that our state is at least nominally interested in a high speed rail project, it would be a good idea to plan for more than just Eugene – Portland – Seattle – Vancouver. Everyone loves to model a high speed rail service off of the Shinkansen (fully separated infrastructure for high speed trains), but forget that major Japanese cities supplement this with narrow-gauge suburban rail that comes more frequently than most US cities metros. Because of the lack of existing passenger service, it’s important to think critically about how the corridor would be utilized.

Speed is Frequency

Even a modestly built 250 km/h (150 mph) line from Portland to the SW suburbs would make an all-stops journey to Tualatin in about 10 minutes. If we could manage to build this, operations would be relatively inexpensive – since it would only require two or three trainsets to maintain 15 minute headways.

Every light rail project in the Portland region suffers from the same problem – they’re too slow. It kills regional transit mobility, and in a fairly sprawly region where the freeway system can get you from one end to another in less than an hour, this really matters. While proposed projects like the Downtown MAX Tunnel are much needed and excellent, even if Blue Line trains could teleport from the Rose Quarter to Providence Park it would still take an hour and a half to ride the line (drive time: 53 minutes in mid-day traffic). Saving 15 minutes/trip also means saving one train, and given that ~6 trains/direction are needed to maintain headways on the Blue Line during the day, this works out to a 16% reduction.

Comparing this to the non-existent SW Corridor, where 4 to 6 trains would be needed to maintain headways (at 30 to 45 minutes of travel time) our high speed suburban line would save a whopping 50% to 66% on labor (assuming 15 minute headways for both). But it’s not really a competition along those lines, so that’s a bit of a moot point. The larger point is that while light rail may have lower capital costs than other rail modes, the lower speeds mean higher operational costs – since it takes more vehicles and drivers to maintain desired frequencies.

Final Thoughts

In any case, by the “Metrics that Matter” methodology, a high speed suburban line stopping at Multnomah/19th, Barbur TC, 68th/99W, Bonita, and terminating at Bridgeport Village scores ~10% better than the SW Corridor. This should be understood as “10% faster for the average trip” – but it’s important to point out that this approach purposefully hamstrings the suburban rail option. If we just compare stops on the suburban line, this jumps to 59% faster for the average trip (with slower trips to other places owing to bus transfers). These are figures that I think absolutely justify a new EIS, even if that process would be lengthy and expensive.

There is something hidden to consider as well though: this would not replace the 12-Barbur bus. A primary reason for pursuing light rail projects in Portland has been because light rail is relatively less expensive to operate than a bus, and removing that incentive makes the project less attractive to our local transit agency. But given that this line ought to be part of a comprehensive high speed rail system throughout the Willamette Valley (as described in this post, and this one), the benefits to regional, state, and interstate travel are too great to worry if TriMet can save a few pennies on cutting a bus line.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t mention that this is an unusual approach for high speed rail. Most mainstream projects are not jumping on the prospect of sharing a right of way with regional trains. But I think in the context of Oregon, it’s worth asking just how many high speed trains need to travel from Portland to Eugene every day. If it’s less than 80 (~every 15 minutes), then we will have made a massive investment in a system that has a huge amount of excess capacity. It is common for the reverse situation though – for a high speed line to take an existing suburban line in to a central station. There are operational constraints, and it can lead to delays. But that cost is worth it – especially for a region like Portland that has zero existing useful regional trains.

And as always, we need to be mindful of the particular context of I5 from Portland to Salem – originally built as the Portland-Salem Expressway as a shortcut to the existing 99E and 99W in the 1950s. Though I like to imagine that interurban services on the Southern Pacific Red Electric and the Oregon Electric lines played a role in the urbanization of the SW suburbs, travel times were slow (more than an hour to Tualatin on the faster OE alignment in 1927), and frequencies never surpassed hourly. As such, there impacts are heavily localized – mostly around major stops like Multnomah Village and Hillsdale. If we hope to have a transit-oriented future in SW Portland, we need a project that will meaningfully compete with travel on I5.

The SW Corridor is not that project – but it should have been. It’s not clear to me what would be needed to change our regions approach either. Light rail is basically the only type of urban transit the US has built in the last 50 years, and as such it’s typically the easiest to fund. Creating this system required drawing inspiration from the German stadtbahns, as well as the streetcars and interurbans of yore. To build a high speed suburban oriented line would be a departure from our current trajectory, but given the current state of the transit world a departure feels like a necessity. We can build a better future, but we need to dream big.

Thanks for reading!

Leave a comment