So as you may be aware, I’ve been following the PGE Harborton Reliability project closely. Since it’s an overlap of both my and Olivia’s interests, it makes for good dinner-time conversation. The project is in the appeals process now, with the Forest Park neighborhood association appealing the conclusions of the city Hearings Officer – who PGE appealed to after the city rejected their permit application. And while this project is interesting for a lot of reasons, I’m going to focus on a very narrow issue – one that relates to rail policy. But first, a bit of background.

A Brief Project Overview

To meet the growing electrical needs of the Portland region, PGE needs to upgrade their electrical distribution networks. To do this, they have identified improving 230 kV connections to the Harborton substation, located just south of Sauvie Island off of Highway 30.

There are a variety of ways that this could be achieved, but the alternative chosen by PGE involves clearing about 5 acres of Forest Park. Evidently, it’s a part of Forest Park already adjacent to existing power lines, but given that the connections being made are from the substation to the line heading over the West Hills (which parallels US 30 around these parts), it seems like there are probably more alternatives which have fewer impacts to the park.

What About Alternative Routes?

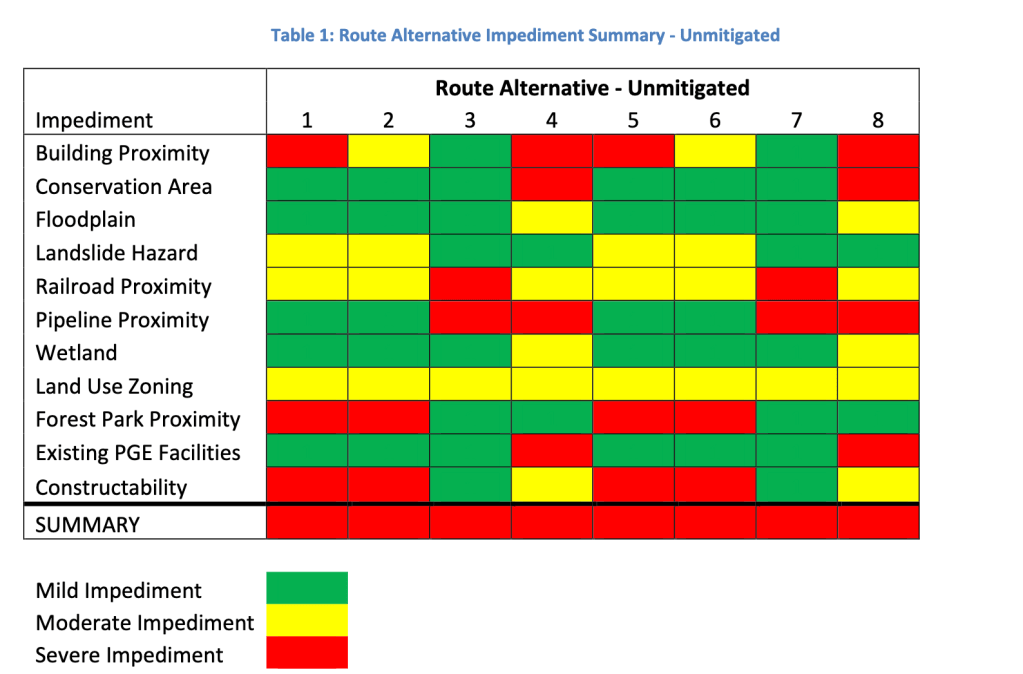

In anticipation of public push back and in accordance with land use regulations, PGE prepared an alternatives analysis back in 2022 for this project. There are eight alternatives presented, which are primarily two sets of four differentiated by which junction point is used. These four categories are designated as Public ROW, East of US 30 (Alternatives #3 & #7); Private ROW, West of US 30 (Alternatives #2 & #6); Private ROW, East of US 30 (Alternatives #4 & #8); and Public ROW, West of US 30 (Alternatives #1 & #5). Of these options, the report identifies Private ROW, East of US 30 as the only feasible choice (Route 8 in the image above). The private right of way in question is PGE’s existing 115 kV line to Saint Helens. But you read the title of this post – what on earth does this have to do with railroads?

In essence, the route with the fewest complications for all categories except railroads and pipelines is Public ROW, East of US 30 (designated as Alternatives #3 and #7 in the report). If you’re familiar with the area, this is no surprise. The land is already owned by ODOT and is between the existing Highway 30 and the Portland & Western line to Astoria (well to Wauna now, but it was originally to Astoria).

Since the study concludes with saying that more than one severe impediment after mitigation rules out an alternative, they are left with just two (or one) – 4 and 8 – despite these being some of the most complex. Yes, they avoid Forest Park, but it also requires relocating an existing power line, acquiring property, and doing additional mitigation near the substation. In contrast, alternatives 3 and 7 (in the public right of way, east of highway 30) have just two severe impediments – neither of which the report considers to be mitigable. If one of those could be mitigated, it would have been considered by PGE for further study.

So now we have arrived at our titular issue – that of railroads and planning. The alternatives analysis report mentions that co-location of high voltage power lines with railroads is problematic because the power lines induce a current in the rails, which can interfere with the signalling circuits. In a typical signalling setup, AC power is used to detect if a train is in a specific “block” of track, something which requires a reliable and appreciable amount of voltage in the rails at all times. Since AC power is used, if a co-located high voltage power line has the same frequency (or a harmonic) as the signal, the induced current can affect if a detection is made.* If DC power is used for the track circuits, the induced current could still be a problem if the magnitude of the induced current is enough to reduce the voltage in the circuit below detection levels.

*at least that’s how I understand it. When the Pennsylvania electrified what is now the Northeast Corridor, they had to change the frequency the signals operated at from 100 Hz (a harmonic of the 25 Hz electrification scheme) to 91 2/3 Hz due to this effect (Wiki Link).

In sum, co-location of high voltage power lines with railroads is only problematic in the case that an induced current is a resonant frequency with the signal circuit, and is powerful enough to meaningfully interact with them. A 230 kV line is probably strong enough to have an effect, but the actual effect is hard to quantify without more information about the railroads signals themselves.

Does Anyone Even Try?

In the alternatives analysis report, there is shockingly little discussion of these potential factors. Instead, the report authors opt for a blanket statement: “If Portland & Western Railroad believes this to be a possibility, they are unlikely to grant a railroad crossing permit. Therefore, route alternatives closely paralleling the railroad should maintain at least 50 feet of separation.”

While it’s true the P&W has the power to deny a permit, if the alternative in question is the most feasible and desirable for the general public, and the effects of the induction are mitigated, would they really be likely to? I doubt it. Given that the line is relatively low traffic (certainly less than five trains a day, probably more like one or two) and P&W is strapped for cash (as evidenced by the recent bridge collapse in Corvallis), I imagine they would be a willing partner in any negotiation. Instead, the report uses the all too common specter of “railroads have power!” to rule out perfectly reasonable alternatives.

It’s ridiculous to imagine that this issue is somehow not mitigable. In this article from a power company in the northeast, they have an example of a 345 kV line paralleling a railroad for 10 miles. If they can mitigate the effects of a higher voltage line over a much greater distance, surely PGE could mitigate this exceedingly minor issue. For Alternative 7, there are just 250 feet of railroad within 50 feet of the power line! That’s a whole lot easier, and the most intensive mitigation I can imagine – fully rebuilding the affected signal circuit – could be done for well under $100k (given that it costs ~$2M per mile to build electrified high speed rail in existing rights of way, this is a hilariously high estimate).

This Seems Crazy, Did Anyone Bring This Up?

The staff report talks briefly about alternatives, but gives no mention of the merit of the alternatives analysis. No doubt folks at the city read the report, so I can only conclude they thought the conclusions were reasonable. I find this to be absurd on its face, but it demonstrates the general lack of familiarity that planners tend to have with railroads (and also electromagnetism, but I got a C in my E&M course in undergrad so can’t complain too much there). And while it’s easy for me to sit here and say something to the effect of “how could you not notice a glaring omission about how mitigable induced currents in railroad signalling are?” this particular rabbit hole only really presented itself to me because I happen to think that railroads are interesting.

In reality, city planning staff are overworked on tight deadlines and don’t often have the luxury of harping on esoterica in appendices. Oregon’s land use system requires tight deadlines, and the primary issues the public are concerned about relates strongly to the impacts to Forest Park. It makes a certain amount of sense to focus more strongly on these aspects of the report.

But it should be obvious that I don’t find this satisfying. What alternatives are actually feasible and why matters a lot for any given project, and by neglecting to fully articulate issues in the alternatives analysis, the city leaves itself in a much weaker position. Would the city be able to compel PGE to do an alternative they feel is infeasible? Surely not. But pointing out factual errors in the alternatives analysis and demanding more specific dialogue about mitigation as it relates to power utilities and railroads is within their purview – especially since land use review in Forest Park does have specific requirements about if alternatives exist outside of park boundaries.

It’s More Than This Project

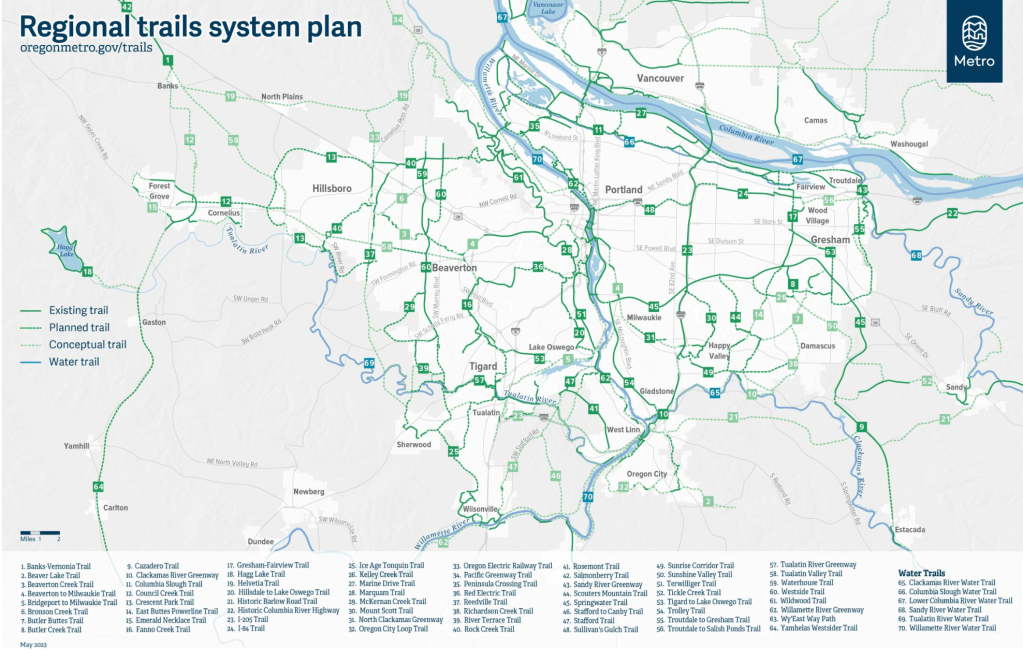

A few years ago, I heard a transportation planner with Washington County celebrate the abandonment of the former Oregon Electric (OE) line from Hillsboro to Forest Grove. Part of the Council Creek Regional Trail, this rail trail project would create a pedestrian friendly route connecting Hillsboro with Forest Grove – an understandably high priority for the county. But something about this just hasn’t sat right with me. Given that the OE line from Beaverton to Hillsboro became the MAX Blue line, it feels a bit short-sighted to convert the natural extension of arguably the most successful light rail project in the country to a trail.

As someone who has ridden their bike and walked on TV Highway between Hillsboro and Cornelius, it’s undeniable that safe infrastructure is needed for non-drivers. While the trail master plan talks about how co-locating a trail with a MAX extension would be possible, there is essentially no public facing dialogue about that now. Whats more, the entire conceptualization of Metro’s regional trails system plan is essentially “identify lightly used branch lines operated by Portland & Western”.

Even though this is potentially legally contentious (thanks to a bogus Supreme Court ruling), as post 1875 railway act rights of way potentially have reversionary rights to land owners before the government (all of these lines were built after 1875), and even though some of these lines have little chance of being abandoned, the instinct of planners is to see a trail as a higher use of land than a rail line. In a lot of ways, this is perfectly natural. Very few of us interact with railroads in any meaningful way. This is doubly true of freight railroading – an industry which has seen something like a 90% decline in employment since its heyday in the pre-Interstate era.

But certain things are inescapable. Trains are much more energy efficient, and despite the fact that the entire freight distribution network has inexorably changed to favor trucks, trains still carry some 15% of all goods in the US. There is no better way to move a lot of stuff efficiently than steel wheels on steel rails.

From this vantage point, every branch line abandonment should be seen as adding more trucks to the roads, further degrading the already horrid conditions and increasing diesel pollution*. Thus, identifying branch lines as “future” trails serves to undermine the usefulness of trains as a means to move goods in the public eye – which would vastly prefer the look and feel of a relaxing path than a line that sees light freight traffic.

*yes, diesel trains also cause pollution but if India can electrify 100% of their rail network, so can the US. The problem is funding, not technology. No, we are not electrifying our trucks in the near future.

On the planning side of things, I think there tends to be a general lack of understanding of railroads and railroad policy. I certainly haven’t gotten a lot of it from my studies (though I have self-selected into many projects with a railroad component). Since railroads have legitimate power to stop projects, there’s a sense of fear they induce. But from another perspective – one where railroads are understood as key components of the region – this fear dissipates. Yes, this limits what a planner can do. Bold regional trail plans that would completely sever the Portland & Western network into two separate sub-networks? Probably not possible. Working with a railroad to site a high-voltage power line parallel to their tracks for 250 feet? Probably possible.

It’s all about identifying the real constraints that railroads have, and working within their legal rights and economic interest.

Reality Isn’t Just What You Make Of It

Ultimately, trail plans on lightly used freight corridors are something of a historical relic. In the heydey of railroad industry mergers and acquisitions, a huge number of duplicate and dubious lines were abandoned. To a large degree, some of this was unavoidable. In the peak of railroad construction, tons of projects were completed that were barely viable even before automotive competition – but federal policy essentially required major companies to subsidize unprofitable lines with profitable ones. When these requirements went away (in response to falling profits in the 1960s and 70s), it was inevitable that abandonments would occur (absent any federal policy to subsidize).

But this isn’t the history you learn in planning school, and railroad policy is something of a niche of a niche. Rather, the public at large (inclusive of planners) saw these abandonments and subsequent trail projects essentially as Pareto improvements – everyone was made better off, and no one was made worse off. Well, at least the people made worse off weren’t readily visible. Who cares about railroad workers and industrial manufacturers?

This era has come and gone, and the rate of railroad abandonments has slowed to a trickle. If a line was able to survive until today, there’s a solid chance it will continue surviving (though this obviously depends on the local manufacturing situation). Whether you’re a planner or just a person interested in this kind of stuff, you’ll have most luck affecting change if you engage with the world as it exists. When planners and policy makers relegate railroads to “scary power brokers who will say no”, they do more than sink opportunities to find cost-effective, politically viable solutions to problems – they undermine their own legitimacy and authority in the eyes of the public.

If you designate the P&W line from Beaverton to Hillsboro as a “conceptual future trail”, but P&W continues to see enough traffic to keep the line open for the next 30 years, all you’ve done is alienate the public and threaten the railroad. We have a dire need for sustainable transportation, but if the best we can dream of is hoping for railroad abandonments, people will not be satisfied. And on a similar note, when staff reports for highly contentious projects miss out on opportunities to press for better solutions at least partly due to a lack of real understanding of railroading, we end up in situations where everyone is worse off.

Like it or not, the American railroad company has been a power broker in land politics for generations. There is no reason to think this will ever change. If planners want to effectively enact change, this is a fact that needs to be recognized and accounted for in a real way – rather than an excuse to discount options in some cases, and hold unrealistic dreams in others. It’s not enough to dream of a better future, we have to actively create it from the one we have now.

Leave a comment