Up in northeast Portland, the Irvington neighborhood consists of the largest historic district in the city. It’s got leafy streets, spacious houses, and all the trappings of a beautiful suburban neighborhood that just happens to be within a stones throw of downtown Portland. So it’s no wonder homes regularly sell for north of a million dollars. But is the neighborhood itself really all that historic? Let’s talk a gander and see what we find.

The Irvington Plat and Irvington Neighborhood Have Different Boundaries

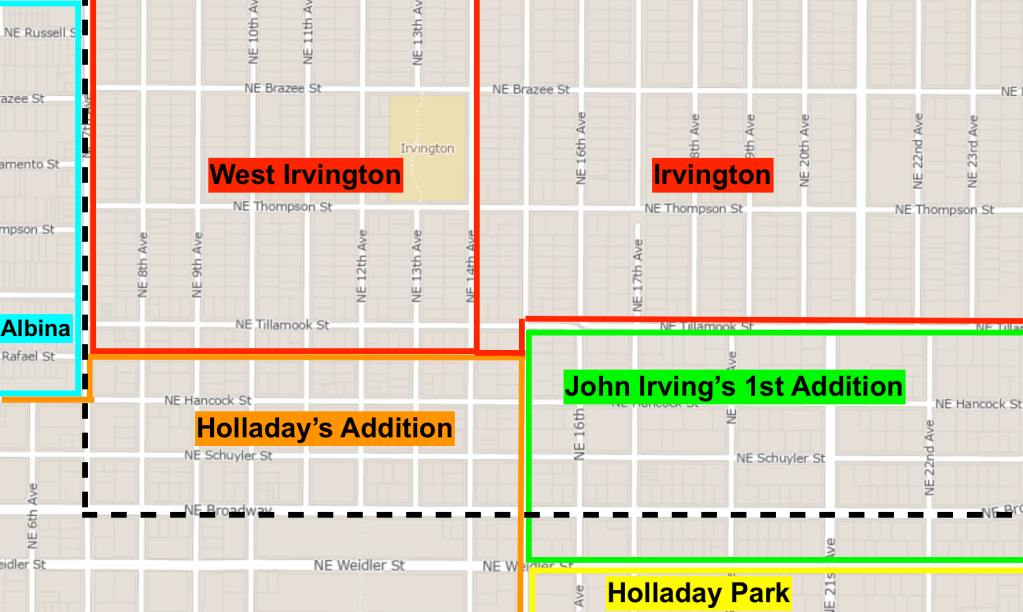

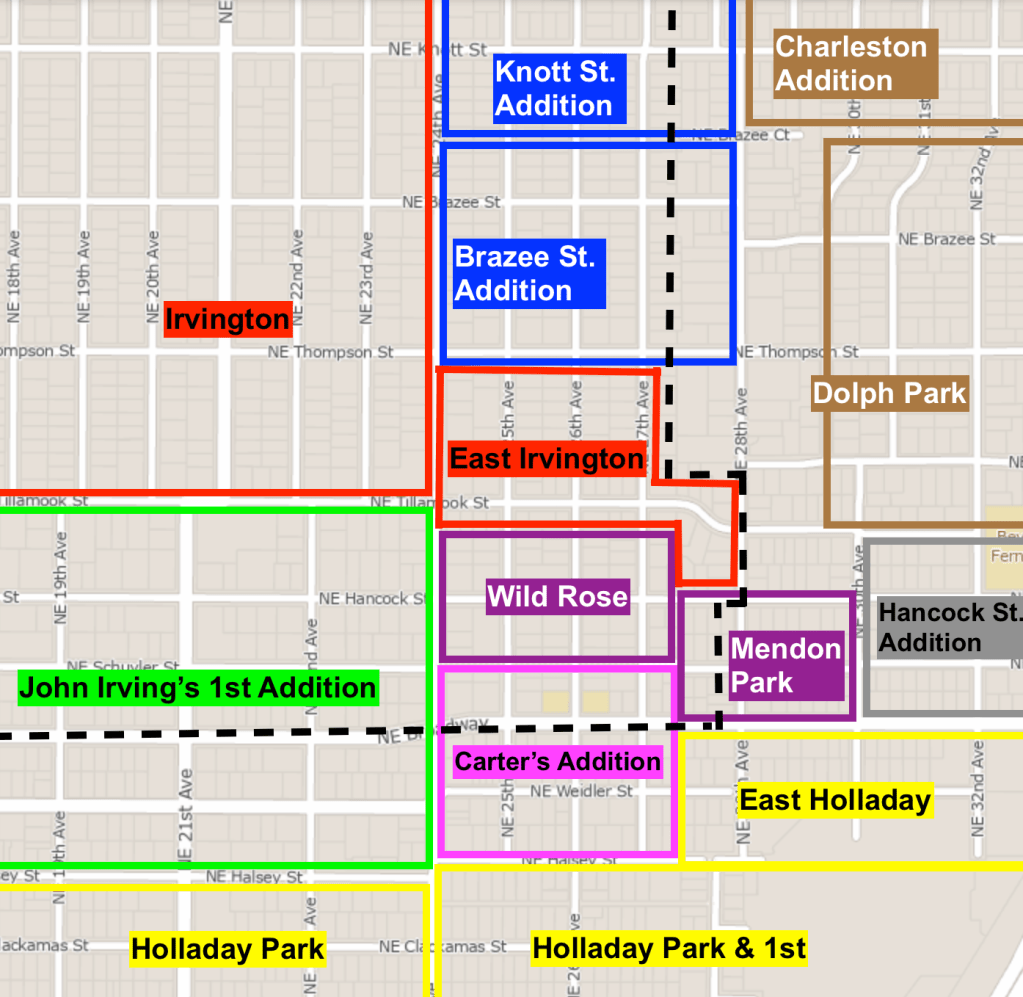

The other day, when I was biking up NE 21st towards Tillamook, I paused to consider why 21st jogs at Tillamook. Having already crossed the official southern boundary of Irvington (NE Broadway), it suddenly struck me as strange to be navigating an off-kilter intersection. So I took a peak at my old friend Portland Maps to see the tax roll description of properties in the area. To no surprise, 21st and Tillamook is the boundary between John Irving’s 1st Addition and Irvington.

Now, the disctinction between “John Irving’s 1st Addition” and “Irvington” feels like a nitpick, but they were not directly related developments. While both relate to the land claims of the Irving family, they came at different times (with the former happening five years before the latter), and with different intentions. Just a glance at the street network for John Irving’s 1st Addition shows blocks that are mostly in-line with the non-Irvington surroundings – with north/south streets that line up with Holladay Park rather than Irvington. Holladay’s Addition further west is also very clearly not part of the Irvington-era developments.

There’s a similar story on the eastern end of southern Irvington, where no fewer than six separately platted subdivisions intermingle. No doubt this contributed significantly to the 2014 attempt to expunge these parts of the neighborhood from the district. This attempt failed, and given that the proposed eastern boundary was NE 21st (very clearly within Irvington proper by any metric), perhaps it doesn’t matter much. While property owners were seemingly seeking fewer restrictions in modifying their buildings, little commentary has been given to what Irvington actually is.

What Makes a Neighborhood a Neighborhood?

In general, the development of Irvington is mostly historical trivia (albeit trivia that matters for the designation of a historic district). If the folks living in the Brazee Street Addition feel like they are a part of Irvington, who are we to stop them? Is there a categorical difference between two homes worth $1M that happen to be on opposing sides of NE 24th? After all, neighborhood boundaries are fluid and change significantly over time. We will return to the point of specific boundaries later, but before we go there I think it’s worth considering that Portland’s very rigid approach to neighborhoods is strange and exists in a peculiar historical context.

In the 1970s, as neighborhood activism took the Portland political scene by storm, the city acted to create neighborhood boundaries that more or less neatly tiled the city. Acting on the dynamics of the time, and often following elementary school catchments, these boundaries are often not particularly reflective of how modern Portlanders interact with the city. If you ask someone what neighborhood the Bagdad Theater is in, the mostly likely response is probably “Hawthorne”, not Richmond. Evidently, most people don’t care about the Office of Civic Life’s boundaries very much – unless you happen to be involved in a neighborhood association.

So in this sense, it makes perfect sense that the area that got designated as “Irvington” by the city in the 1970s was larger than the original subdivision plat. Acting on the local political dynamics of the time was clearly more important than sticking to the decades old plat boundaries. If that 1970s era designation is still relevant is a matter of taste, but if you go down the path of historical conservation as a means to prevent development as Irvington has, it becomes a key factor in where development can occur in the city since the neighborhood association was intimately involved with the historic designation process. It makes sense that they would start with their own borders and work from there.

The parts of Irvington which are least like the leafy suburb developed by the Irvington Investment Company in the late 1800s are primarily the parts they did not develop. This is obvious to anyone who has every traveled down Tillamook – one of the dividing lines, and a neighborhood greenway. To the north are stately single family homes, while to the south is almost exclusively apartments (especially clear east of 17th, where it is the actual dividing line rather than a close approximation).

Whatever We Call Irvington, the Current Historical Designation Boundary is Dumb

Based both on the plat maps and the general feel of the area, it seems to me that including non-Irvington named developments in the historic district is dubious. While the area bounded by Tillamook, 7th, 24th, and Fremont (approximately the original plat boundaries) is easily recognizable as “definitely Irvington”, the rest of the area should really have been left out. Yet, in the application to become a historic district, there are quotes like:

“While the district boundary is reflective of historic plat and land development patterns throughout the district, the boundary also reflects important physical differences between the nominated area and the surrounding neighborhoods in terms of geography, lot size, property use, and historical integrity.”

This is simply not true, and is especially not true south of Tillamook (and east of 24th). A quick survey of contributing buildings does show fewer buildings listed south of Tillamook than north, but the status of a 1919 apartment (2170 NE Hancock, below) that is not in the Irvington plat as contributing to the integrity of the historic character of Irvington is dubious at best.

One of the most notable parts of Irvington’s history is its status as “as an excellent example of a ‘streetcar suburb’ that used restrictive covenants* and for its exemplary collection of residential architecture constructed from 1891 to 1948.” I would not challenge the merits of the architecture of any specific building that is near the Irvington plat, but those could be registered on their own if they meet the criteria. I think 2170 NE Hancock is a cool looking apartment; does it really relate to an area that is essentially all single family homes, mostly developed for the well-to-do?

*a note on “restrictive covenants” here: while the Irvington deed restrictions explicitly excluded Chinese residents, they also deal with uses and setbacks (“A Vision For Irvington“). In pre-zoning world, deed restrictions were commonly used as a sort of proto-zoning. And I don’t mean to minimize the social damage of Chinese exclusion, but compared to the scale of other contemporary Portland racial deed restrictions (looking at you Laurelhurst), it’s not as significant. But also worth saying that much of the anti-Black racism in Portland functioned extra-judicially anyways – Black residents were excluded from most neighborhoods by overt terrorism rather than legal fine print (exemplified by the story of Dr. DeNorval Unthank being forced to move homes four times in places he was legally allowed to buy).

Rather, the southern reach of the Irvington neighborhood were included in the neighborhood in the 1960s based on the presence of significant commercial activity on Broadway that residents of Irvington proper identified with. I find this to be sort of interesting in itself – the process by which neighborhoods form in the collective imagination and what we consider to be natural edges of neighborhoods – and this commentary is present in the historical designation of Irvington. But discussion of Broadway as a “logical outlet for commerce and more dense development” only begs further questions. Why not MLK? Large parts of the Irvington plat were more accessible to MLK (then Union) than they were to Broadway. And most parts of east Portland broadly resemble an Irvington-Broadway relationship – residential areas surrounding commercial corridors. I just don’t buy that Broadway is part of Irvington by extension – especially when it’s not the only neighborhood bordering the street.

Furthermore, commentary about Broadway becoming a commercial center “by the 1920s [as] more intensive commercial development began to emerge once the restrictive covenants had expired” is not backed up by evidence of deed restrictions for the areas that actually border Broadway. You don’t have to look very far for buildings on Broadway that are purpose-built commercial buildings predating the expiration of deed restrictions in Irvington in 1916, but postdating the opening of the Broadway Bridge in 1913 (1332 NE Broadway, built 1915 and 1716 NE 24th, built 1914 for example). Broadway is a commercial corridor because of streetcar lines emanating off the Broadway Bridge, not because of Irvington’s deed restrictions.

What we have in the designation of Irvington is an interesting contradiction. Including “Irvington” as the public imagined it – the current boundary – necessarily means distorting the historical truth about what Irvington actually is in the context of the built environment. Does this matter? I’m not sure, but I think if a historical district seeks to leverage some specific piece of history, we have a responsibility to do so accurately to the extent practical. The choice of including parts of the Irvington neighborhood not developed in conjunction with the Irvington plat vacates this responsibility to serve no particular end other than the preservation of existing arbitrary neighborhood boundaries.

What Does It All Mean?

Even though Irvington does have a mildly interesting history – especially the relationship with Albina and Black Portland in the 1970s – I find the narrow focus on the maintenance of 20th century trends in single family home architecture to be of little public interest. And whats more, Irvington is hardly unique for Portland residential subdivisions. Most early 20th century building in Portland happened in conjunction with streetcars, and the single family home was the de facto standard (that then became institutionalized with the first zoning codes in the 1920s and 1930s). And Irvington’s own historical registry application emphasizes its stylistic heterogeneity.

So what makes Irvington so unique and worthy of preservation? If you read between the lines, or you know me personally, the answer I’m about to give is obvious: rich people live in Irvington and wanted to maintain a specific vision of their neighborhood. This is why the boundary inconsistency is ignored – the vision of what Irvington is starts with the modern homeowner’s conceptualization of the neighborhood, not the original plat. Suffice to say, I don’t find this very compelling.

Historic districts should be about more than “rich people live/lived here”, they should have some broader relevance to the place they are within. Places like Downtown Savannah, Georgia have obvious historical relevance (even if this history isn’t exactly savory as it relates to slavery). You could argue that Irvington, Laurelhurst, and Eastmoreland (Portland’s largest historical districts) are worth preserving insofar as they exemplify early to mid 20th century exclusionary housing practices, but this immediately falls apart if you consider who the primary benefactors of historical designation are: homeowners in the area who also financially benefited from exclusion.

Does a city that is essentially suburban in character really need to self-consciously preserve three separate neighborhoods (Irvington, Laurelhurst, and Eastmoreland) that all tell the same story and are at no real risk of being lost? Probably not. Even though their preservation does run counter to city and state policy emphasizing infill – thus implying a “need” for preservation – it’s worth asking if we really lose anything of public value when a stately home is minorly altered to make way for a small n-plex.

Redevelopment is a politically contentious thing, and there are many problems with it – first and foremost the resources expended to do so, rather than reusing existing structures. From this vantage point, the historical designation process can be a boon – since it strongly encourages (or requires) the maintenance of the building envelope, while allowing for flexible uses of the interior. Subdividing a single family home in Irvington to a quadplex is the best of both worlds – adding more housing* while taking the environmentally friendly choice of re-using an existing building.

*at a future date, I will be exploring the relationship between housing units and actual population density. I think too much of the dialogue around the housing crisis focuses on unit production and not enough of it focuses on household size and our social construction of allowable living arrangements. Here, I mean “more housing” in the strictly normative sense of “dwelling units” but don’t think this is the only interesting way to think about this.

I feel that this is ultimately a bit of a moot point. Sure, it’s nice that historical districts encourage the re-use of buildings, but the justification for them existing is still in the fact that they are historic – not the positive knock-on effects. Even if the Irvington Historic District were retracted to be just the boundary of the actual Irvington development(s), the fact would still remain that I don’t really think it’s a development we should be preserving.

For me, it’s a question of what history is worth valuing. The character embodied in an older single family home can be interesting, even fascinating, but history is ultimately about stories. The story told by preserving Irvington is more than that the stately manors of the professional class are worth keeping around in perpetuity, it’s that we should spend public resources to do so. The fact that the boundary claimed as “Historic Irvington” is much larger than the actual Irvington development is just salt in the wound. If we want Portland to be a city which positively reflects our values, we can’t just sit by and watch the historical registry be abused for spurious reasons. We have a lot of stories worth telling in the built environment – let’s highlight those instead of focusing on where rich White people lived in the early 20th century.

Thanks for reading – til next time.

Leave a reply to adventurepdx Cancel reply