If you live in Portland and ride a bike, you are no doubt familiar with the neighborhood greenway network. A series of low-traffic, neighborhood streets they offer a (mostly) low-stress way to get around the city on a bike. The network has formed the majority of the bikeway buildout in Portland since the adoption of the 2030 Bike Plan in 2010. Since we are just a few years from 2030 now, it’s worth looking at how this has gone – and if the goals of the 2030 plan have lived up to reality.

Goals and Framework for 2030 in 2010

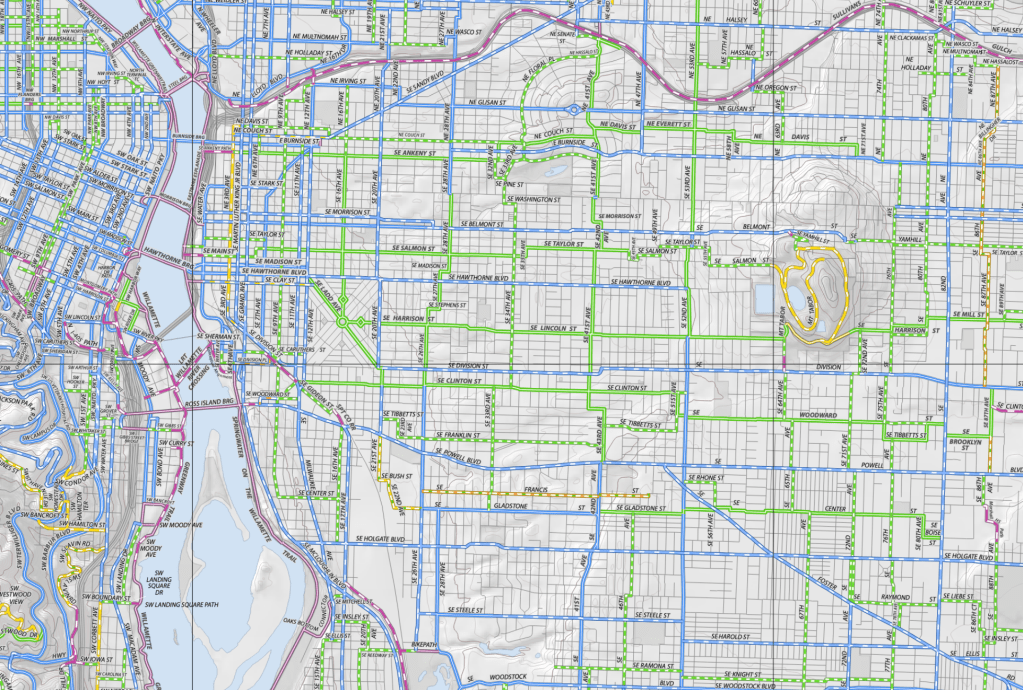

The 2030 Bike Plan conveniently identifies five parameters in the identification and planning of prioritized projects. They are connectivity, classification conflicts, existing traffic conditions, existing traffic infrastructure, directness, and mobility. These criteria are used to pare down the expansive list of bike infrastructure provided in the full map (below) into a project list that can be prioritized in a way that planners believed to be both feasible and useful.

And while each of those six criteria make sense – a straight road that connects the major destinations of the city with low traffic streets would be a slam dunk – they are almost always in conflict with each other. Most poignantly is the conflict between traffic/road classification with directness/connectivity. To understand how this conflict came to be, we need to take a brief detour to the history of urban development in Portland.

Before the 1920s, city planning as we know it now functionally did not exist. It wasn’t until the creation of the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act in 1922 (model code developed by Herbert Hoover et al.) and the landmark Euclid v. Ambler Supreme Court case in 1926 that proactive land use planning was widely accepted and legal. Portland’s first zoning code was ratified in 1924, and before this the city did not proactively regulate land use, nor was there a uniform or planned annexation and subdivision process.

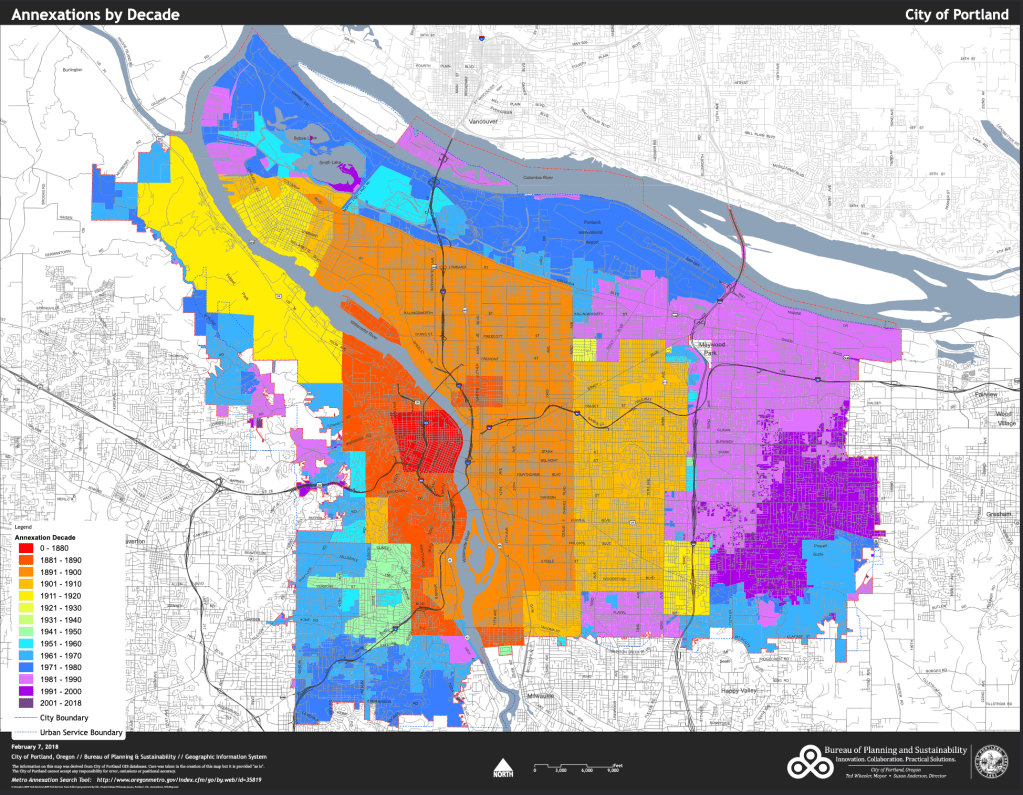

Consulting this map of Portland’s annexation by decades, and we find that the vast majority of land in what we now recognize as inner Portland to predate the 1924 zoning code.

What this means in practice, is that for most residential subdivisions and subsequent annexations, there was no guiding policy on how to do simple things like connecting streets. Additionally, subdivisions were not built out in a uniform way from the center of Portland, so further out subdivisions often just made their own street grid. Thus, at the boundaries of old subdivisions you often find places where streets “jog” (that is, come to an intersection offset).

However, some streets in Portland predate urban development – either because of their status as rural trails/highways (like Sandy, Powell, and Foster), because a streetcar was there (like Belmont, Clinton, Mississippi, and Williams), or because they were survey division roads (like Division, Killingsworth, Fremont, and Stark). Thus, developers were forced to integrate these existing streets into whatever grid they dreamed up – and in the latter case, they often served as boundaries. I’ll refer to these three categories of roads (alongside later additions like state highways) as “historically logical routes”.

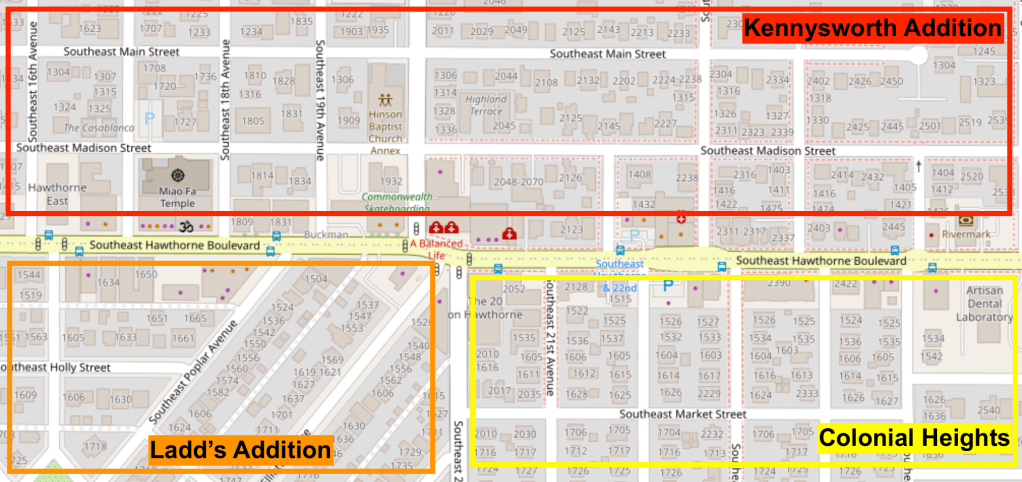

Why is this important for our discussion of bikeway planning? Well it means that there are a limited number of streets which meet the criteria of providing directness, connectivity, and mobility since the neighborhood street grid is not coherent across old subdivision boundaries. It really is only the historically logical routes which break this mold. Below, we can see how this occurred at the tripoint between three subdivisions (often called “additions”) in SE Portland. Of course, Ladd’s is notorious for it’s “different” street grid, but you’ll also notice how roads like SE 22nd, SE 23rd, and SE 16th jog at Hawthorne (the old streetcar line) even where they don’t encounter a Ladd diagonal.

As someone who enjoys random inconveniences of arbitrary decisions made by people 100 years ago, I usually don’t have an issue with Portland’s wacky grid. I find it to be sort of charming. But if the goal is to find a straight, city-scale, connected street, you’ll usually be out of luck consulting a neighborhood road. So of the six 2030 plan criteria, you have three which call for direct, straight, and useful connections and three which call for existing low-traffic streets. And because no street has them all, when implementing these criteria planners inevitably have to make a choice about which is more important.

What Matters More? Low Traffic or Good Connections?

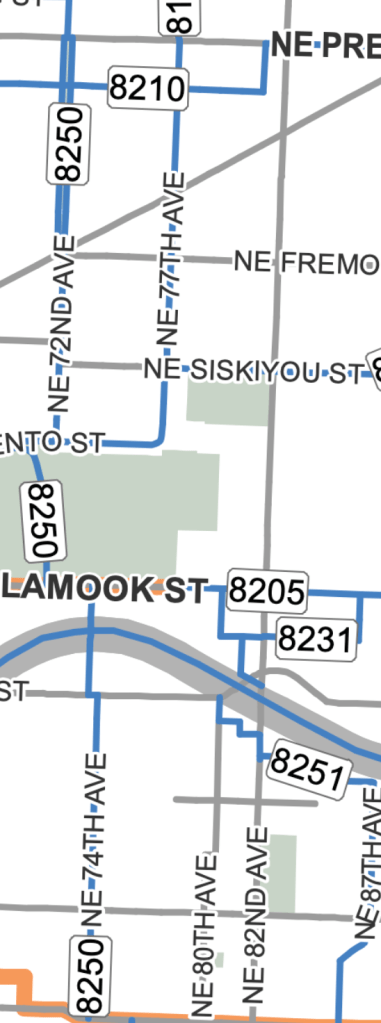

Further along in the 2030 plan, we can find the three categories of project. First, are the existing bikeways (orange), second are the immediate projects (blue), and third are the “world class” projects (grey). In this snippet of NE Portland, we can see that the 70s route (74th/72nd/77th) between Prescott and Burnside is blue, while 82nd is grey. 82nd is clearly the preferable option on the first set of categories (direct, straight, serves many destinations), while the 70s route is the choice of low-traffic streets intended to be roughly parallel.

There are innumerable examples of this in the plan. But since our existing roadway classification network has already reserved the historically logical routes for arterial and collector roads, the bike plan is “forced” to work around them.

I say “forced” because this is a tacit policy choice. There is no law of the universe that says “bikes belong on windy streets, cars belong on straight roads”. That said, the choice to prioritize low traffic streets over those with straight, logical connections is understandable in many ways. In the pre-2010 days, much of Portland simply had no bike network of any kind. It makes a certain amount of sense to maximize the coverage of the network to ensure that everyone has a little, rather than some places having a lot. If it’s easier and cheaper to do this on neighborhood streets, I can at least understand the reasoning (even if I disagree).

But the relegation of essentially all in-roadway facilities on major roads (i.e., bike lanes on historically logical routes) to “world class” projects serves to undermine some of the key recommendations made in the plan. At various points, the plan emphasizes the need for visibility, for directness, and for connectivity with commercial corridors. For this expansiveness, the plan was widely lauded, but the Faustian bargain contained within it went largely ignored.

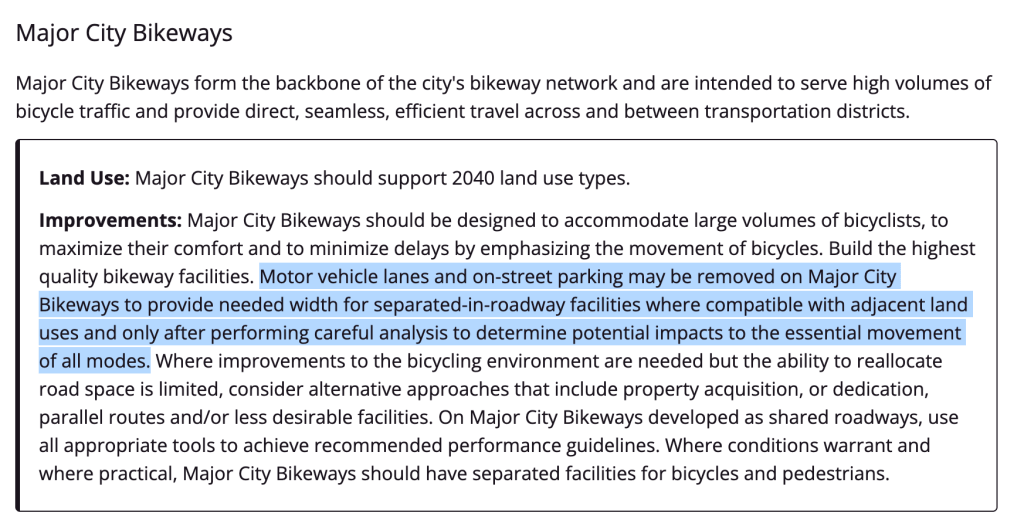

While the implementation framework understandably has to make these trade-offs, it’s not clear to me that the basic designation of roads should have. Within the 2030 bike plan, there is a new Transportation System Plan (TSP) designation category for bikes. The three categories – “Major City Bikeway”, “City Bikeway”, and “Local Service Bikeway” – are used to determine which roads are which priority for cycling. A local service bikeway is just any road where it’s legal to ride and where no other designation is given, so the only distinguishing factor of note is between the Major City and City designation.

Within the plan, this distinguishing factor between the two is primarily the relationship to other modes. Thus, outside of a few exceptions, the Major City Bikeway network does not overlap with the other major modes (traffic, emergency response, transit, and freight). Hawthorne is a City Bikeway, since it has high priority for traffic (District Collector), emergency response (major), transit (major), and freight (truck access). Thus, when the redesign for the corridor came in 2019, there was not as strong of a planning impetus for putting bike lanes on it than there was for maintaining other access.

Other modes do not have this relationship with each other – at least not in the same way. The Major City Walkway Network lines up neatly with the priority car network, which lines up neatly with the transit priority network. This is hardly surprising given the context of Portland’s history and extant land use policy, with limited historically logical routes to choose from, most of which are zoned for intense, pedestrian-oriented commercial use of some kind.

This is to say that the inherent properties of the street are used to designate the other TSP modes, while biking forces itself to avoid highly prioritized roads for other modes. Rather than let future planners and advocates decide how to prioritize modes on streets with many priorities, that decision was made at the definitional level. There are some streets where this dialogue is forced (like Sandy), but those are few and far between.

There is no real reason to do it this way, since the TSP is more of a set of guidelines than a binding truth. The TSP is at least partly aspirational, and by limiting the highest designation of bike routes to essentially neighborhood greenways, the 2030 bike plan does more than just say that low traffic wins out over good connections in the immediate, tangible future. It also says that it should be that way.

I’d like to imagine this wasn’t purposeful, but this is still something that needs to be addressed immediately. It has clear ramifications for future bike policy. When even the Major City Bikeway wasn’t enough to get NE 28th a bike lane treatment (due to strong business association opposition due to parking concerns), what hope do any of our major commercial corridors really stand of having reasonable bike access?

A Greenway Only Bike Plan is Doomed to Failure

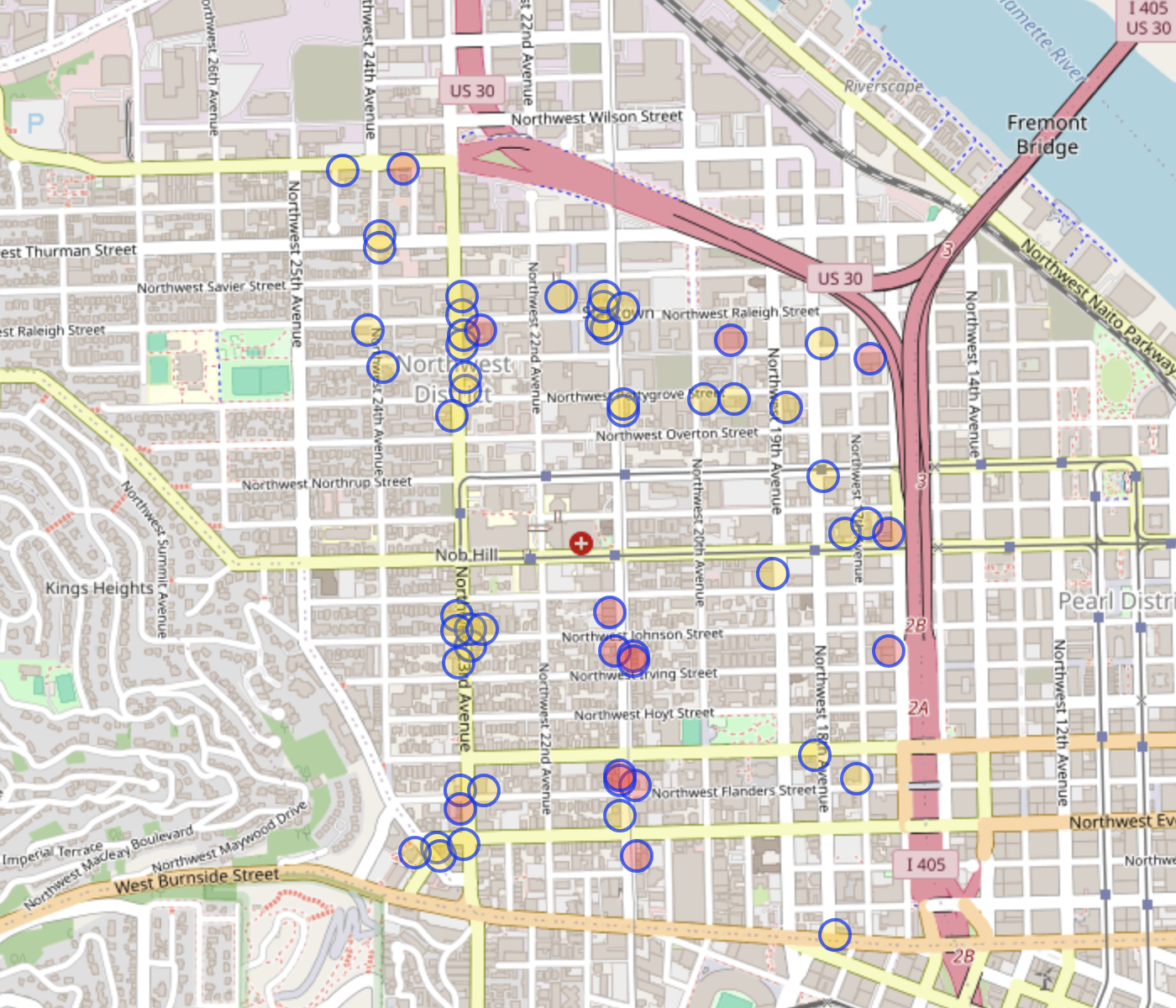

Even though I love riding on greenways, they too suffer from the lack of supporting infrastructure. As we’ve seen, making neighborhood streets the backbone of any transportation network is a losing strategy in Portland owing to the dearth of historically logical routes to choose from. But even if this weren’t the case, building the backbone of a network without the local distribution system is perilous at best. Let’s take a look at how access in this kind of system manifests itself with a case study of Northwest Portland.

As you can see above, of the 131 bars, cafes, pubs, and restaurants located in the 1.6 square mile Northwest District neighborhood, just 60 are within a half-block (50 meters) of a bikeway. In this part of Portland, there is street parking for cars on every block – meaning that all 131 of these institutions are within that same 50m radius for automobile access (of course, actually parking availability may vary – but we still generally plan for as much parking as possible in close proximity to business districts).

Evidently, if you’ve ever biked down to Northwest for a pint to meet up with your good friend Clark like I have, you’ll be quick to point out that you can just ride on undesignated bike routes to get the last few blocks en route to your destination and lock up out front. This is absolutely true, but not everyone enjoys biking on a busy road like NW 23rd with no facilities, and if we care about good bike access to the unfathomable number of retail locations on NW 23rd, “well, good luck!” is not a very good policy.

What this example illustrates is that even if you believe that the greenways are effective as the “backbone” of the bike transportation network, without local connections the network is guaranteed to be stressful at one or both ends of every trip. Now, I’m an extremely experienced and generally assertive bike rider. I don’t mind taking the lane on NW 23rd or 21st, but even I have my limits. When I ride my bike to places on Powell, or 82nd, or MLK I really have to think my route out in advance or risk ending up in the gutter of an objectively dangerous road.

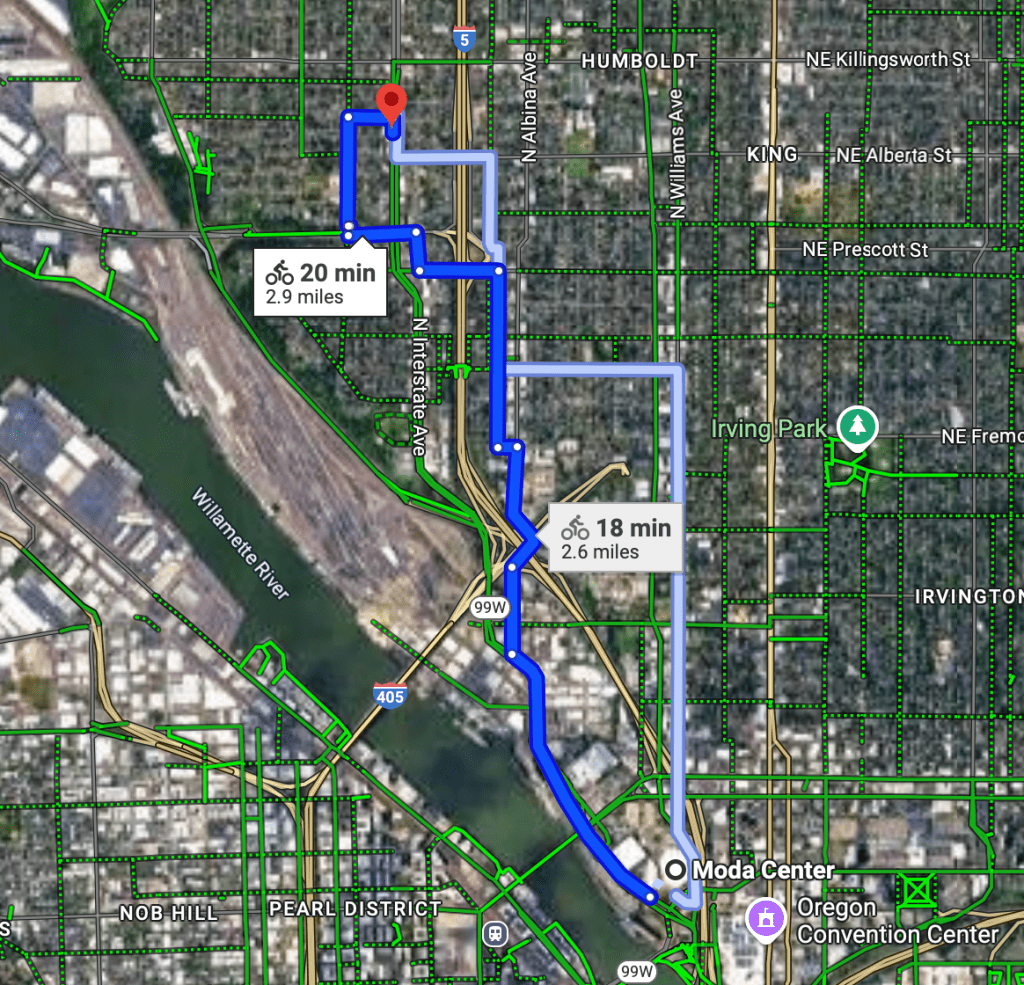

Just one experience like this for an inexperienced rider is probably enough to turn them away from cycling as a legitimate means of transportation. Services like Google Maps don’t usually suggest riding on MLK, but it will tell you to bike up Mississippi from Interstate – something I would not personally recommend. I get that the “ask some guy in Portland what the best route is” method isn’t very scalable, but that is essentially how the current bike network functions. You either ride a lot, meet up with folks who have, or you stop riding.

What’s Next for Cycling in Portland?

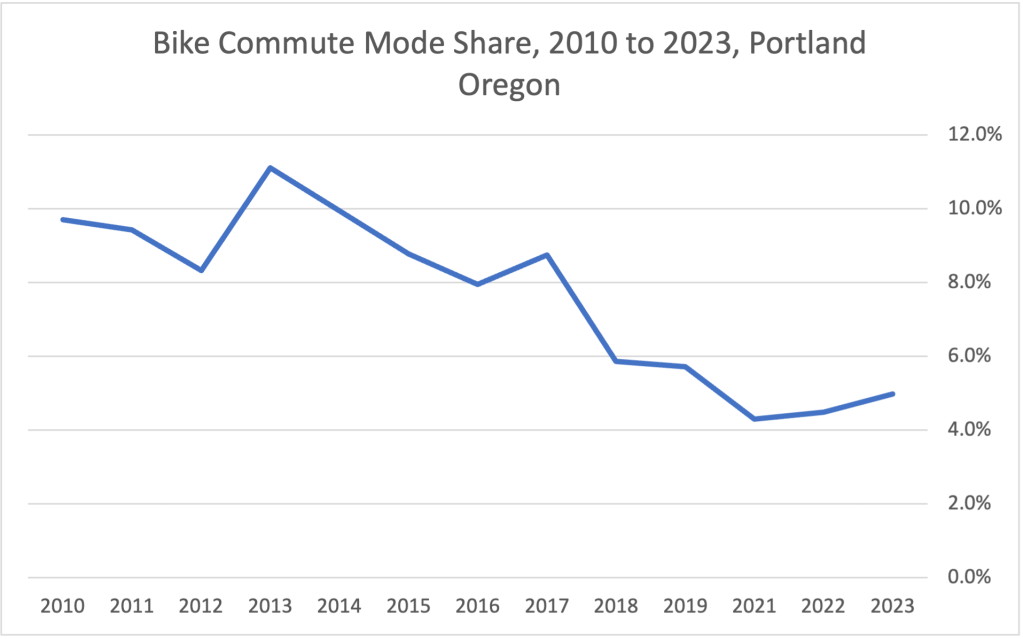

It’s clear that cycling is very much not in vogue in Portland these days. Gone are the halcyon days of yore when the cycling revolution was here to stay, and 25% of mode share by 2030 felt more like an inevitable future than a distant dream. Tracking mode share for cycling from 2010 to 2023, and you’ll see a steep decline that predates Covid by a few years. Going from more than 10% to less than 6% before widespread work from home demands some explanation

While there is a lot of discussion about how falling mode share can be attributed to lack of urgency and progress in implementing the 2030 Bike Plan, I am not convinced of this for two reasons. The first is that there is little evidence that conditions for cycling got worse in a meaningful way, and the second is that I think the 2030 Bike Plan hamstrung planning for bikes through poorly articulated TSP policy and project prioritization that centered an only greenway and tiny gaps strategy.

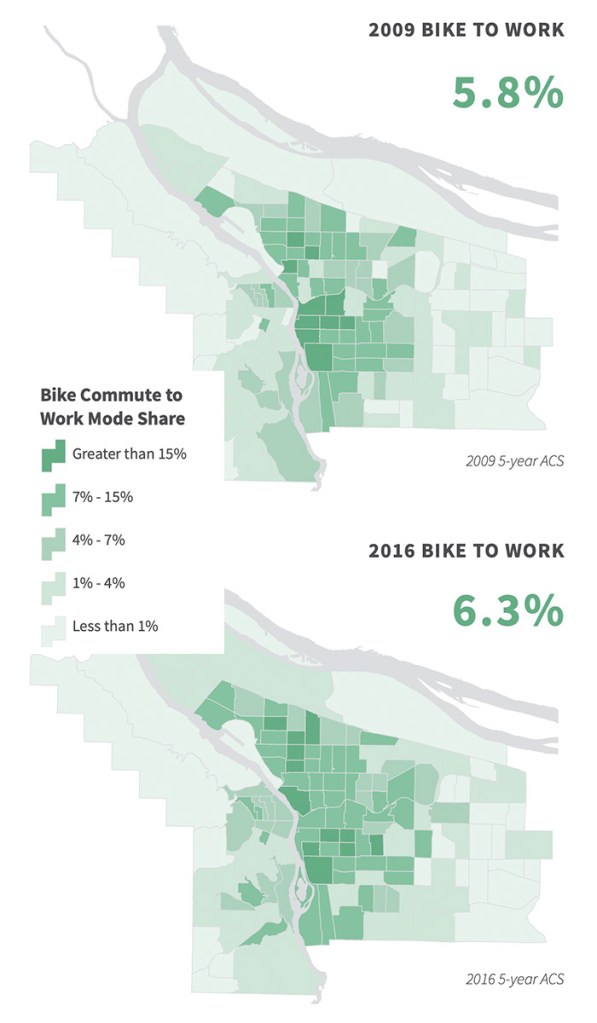

Instead, I think the falling bike share is a result of a minor part of the 2019 plan update report. In this report, the “decentralization of cycling commuters” is noted. As inner Portland neighborhoods continued to gentrify in the late 2010s, the folks who moved in were less likely to ride a bike to work than the ones they replaced.

To me, this is a mechanism that does explain the falling bike share in a real way. While biking to work in Portland through most of the 2010s was a higher-income earning affair, the people who did the riding likely skewed younger.

Thus, when folks moved out of smaller central city apartments in Kerns and into detached homes in Woodlawn, some of them continued on their merry way riding a bike – but the folks who replaced them in these inner Portland neighborhoods did not. The pace of demographic and social change in inner Portland was fast enough that formerly entrenched parts of daily life did not reproduce themselves.

But even under these circumstances, the social aspect of cycling in Portland still looms large. Things like Pedalpalooza, the WNBR, and the Bridge Pedal attract crowds which rival the peak bike days. It’s just that cycling seems to have become a pastiche of itself – reduced to a fun social activity you do a few times per summer rather than a practical way of life. People who want to ride only do so in the ways in which the network can accommodate, and fun social rides is certainly something that can be done on Portland’s bike network.

Luckily, since the social aspect of Portland cycling is still strong even in the face a middling network. It goes without saying that it’s a key resource in any future rebound. It remains to be seen how or when this may happen, but as long as there are people in Portland who love cycling, we may just need some spark to restart the party.

Parting Thoughts

If we are serious about improving cycling (or walking or transit), we need to have plans which make it possible to change our world. While Portland is lauded for it’s transformative planning, I find that worryingly little ends up transformed. More of the cycling boom years seem to have been driven by non-planning related items (culture, demographics, and gas prices), and the “build it and they will come” mantra never worked out – in part because “build it” mostly meant neighborhood greenways and little else. From our vantage point now in 2025, it’s hard to view the 2030 cycling plan as anything more than a failure.

Good plans balance aspirations and reality in a way that allows for achievable projects to be built without undermining our aspirations. How many aspirations of the 2030 bike plan have been realized? Even the Faustian strategic implementation plan, focused solely on neighborhood greenways and new trails comes up short. To date only one of the three major trails is even remotely in progress (and that is mostly to do with the tireless work of SW Trails), and most greenways lack even cursory diversion infrastructure. For the “world class” designated projects, I can only identify one that PBOT has followed through on (SE Foster), and two that ODOT has (SE Powell and N Lombard).

Reality needs to be reflected in a plan, especially for implementation. But the 2030 bike plan and the current TSP do more than this. They bake our current reality into the future of our bike network by tying bikeway improvements to the balance of all modes at the definitional level. If we sincerely believe that cycling is a way forward, then our plans need to believe that too, and they need to create space for a future where things are actually different and better.

I’ll remain stubbornly optimistic about this better future, and hopefully you all will too. Thanks for reading.

Leave a reply to cityhikes Cancel reply